CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

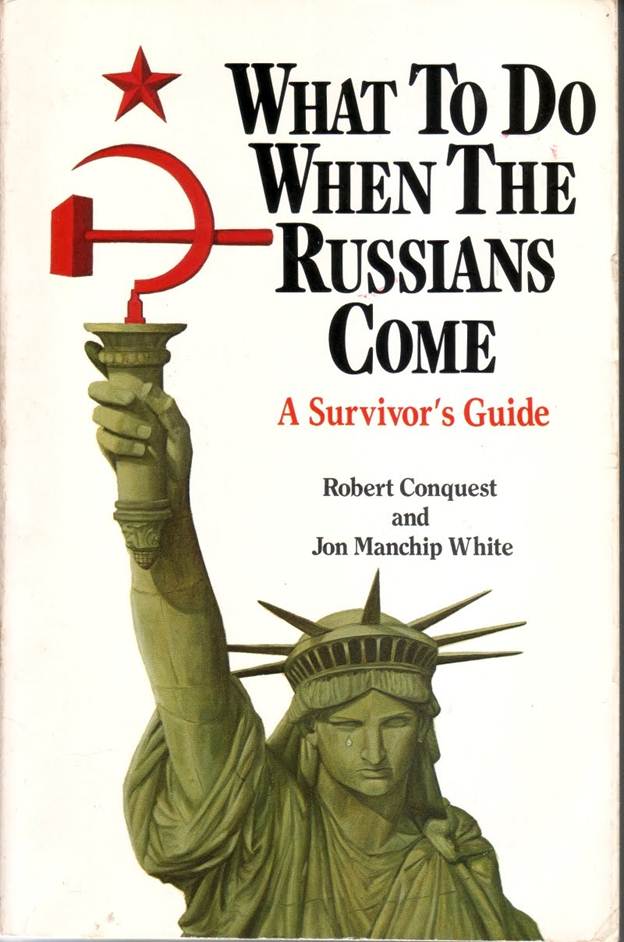

WHAT TO DO WHEN THE RUSSIANS COME

A NOTE TO THE READER

It is widely accepted that the United States now faces a real possibility of succumbing to the power of an alien regime unless the right policies are pursued.

It is not the purpose of this book to argue which policies are right. Its aim is quite different. It is, first, to show the American citizen clearly and factually what the results of this possible Soviet domination could be and how it would affect him or her personally; and second, to give some serious advice on how to survive.

How can you, the individual American citizen, expect your personal record to be treated by the new masters?

What kind of existence, under Soviet domination, can you look forward to?

Will there be any possibility of protest, resistance, and revolt; and what forms might they take?

This book offers you insights into what it will be like and advice as to survival behavior in the far-from-impossible event that this is what the future holds in store.

You should not take what we say as some horrible fantasy. Every word is based on the actual experience of hundreds of millions of ordinary people, in a dozen countries—people like yourself, most of whom had no more thought of the possibility of what actually happened to them than most Americans do today.

FOREWORD

Try to picture yourself as you might be in ten years time, perhaps less.

We are assuming that you are one of the lucky ones.

None of your family have been killed, except a distant cousin shot in the street early on, and your brother-in-law in the marines who was executed as a war criminal. None of the women have been raped.

Your job was one of the many that ceased to exist, and your savings have been extinguished by the “currency reform,” but you had enough food and fuel to carry you through until you found your present low-paid post in one of the huge new rationing offices.

Your home was not wrecked or even damaged. And it was not impressive enough to be confiscated for the new elite or for Soviet officers. You escaped strangers being billeted on you by quickly settling into it a couple of families of friends who had lost theirs. You get on reasonably well, and although there is inevitable friction and the occasional flare-up, you are long since used to the overcrowding.

You had a tiring trip to work, changing twice between jam-packed buses; but it really is too far to bicycle. Once in the office things were fairly quiet, except that the ex-economics professor, who sweeps the floors and tidies up the washrooms, grumbled when they came around for the weekly compulsory contribution to the State Loan. How long can he last if he keeps doing that?

On your return journey you got your permit to visit your old parents in a neighboring state next month, after waiting only an hour. And when you drew the potato ration, you were pleased to find it was practically the right weight and of reasonable quality, capable of making a decent meal when you mix it with one of your bouillon cubes. What’s more, while waiting in line for it, you met a friend who told you where some apples were available, and you hurried over there and managed to get a couple.

So here it is, only nine at night and you are already back home. You have not had time to look at the paper, but when you settle down to read it, there is little except news of Soviet industrial and artistic achievements and speeches by American Communists recently back from Moscow. You do notice an account of the trial of a dozen local officials for sabotage; but they are not from the Department of Agriculture, so this does not mean another famine. You start to remark on this, but you quickly break off. The children are around, and the younger ones might unthinkingly repeat what you say somewhere outside or at school.

Your ears catch the crunch of boots at the end of the street.

A Soviet platoon goes past. You automatically draw back still farther from the window. But it is only a routine patrol, not one of the special squads, so you relax as you see the helmets flickering in the red glow of the lone street lamp.

Yes, so far you have certainly been lucky. Next door, the old schoolteacher was arrested a few weeks ago for failing to abuse President Truman in a history lesson. Half a block away, the chairperson of the local Democratic party resisted arrest and was shot on the spot. (Her Republican opposite number, from [10] another section of town, is in the uranium mines in Northwest Canada and rumored to be on the point of death.) The widow in the house across the way had a son in the FBI, who has vanished without trace. And the Chinese couple a little farther down have been deported. ...

Suppertime. A delicious smell from the Primus stove—the potatoes are nearly boiling. Tomorrow is another day. Today, at least, has been uneventful ... a good day.

This may not happen.

But, on the other hand, IT MAY ...

How could such a state of affairs come about?

First, we will consider the ways in which, after the initial confrontation, the Soviets will establish their grip on the political organization of the United States and the ways in which this will affect the ordinary citizen.

Then, we shall deal with the most immediate dangers facing you if you are not one of the lucky ones: arrest and dispatch to a labor camp or exile, a fate that will not overtake everybody but one that will be common enough to be a very serious risk to almost all of you, affecting probably some 20 percent of the adult population. We seriously believe that the advice we give in this context, and on the possibility of escaping abroad, could save thousands of lives.

For those who have not been arrested, or not yet, we describe the problems of ordinary life, with advice on how to cope with them.

We go on, in chapter 5, to consider how particular people are likely to fare. For our readers are not merely citizens. They are farmers, industrial workers, doctors, students, clergymen; they are Republicans, Democrats, Socialists, “New Leftists”; they are Polish Americans, blacks, Chinese Americans, Jews: and they are all the other things Americans are. [11]

We then analyze the quality of life: coping with the bureaucracy and with informers, crime and travel, conscription into the American People’s Army for wars abroad, personal relations at home.

And we conclude with an examination of the prospects of resistance, in both the short and the long terms, concluding that it is even possible that some readers may survive to see the rebirth of freedom.

Let us repeat, everything we tell has been the experience of great populations. We are not even presenting a “worst case.” We have not transferred to America the mass slaughters such as the Terror of 1937–1938 in the USSR, that have been inflicted in a number of Communist countries. Things may be worse than we have outlined. At any rate, they will hardly be better. [12]

WHAT TO DO WHEN THE RUSSIANS COME

1. THE FIRST SHOCK

THERE ARE SEVERAL ways in which disaster might strike America. We cannot totally exclude an all-out nuclear war that is so destructive that little is left of either side; or one in which America is largely destroyed with far less Soviet loss, resulting in the occupation by Moscow’s troops of a ruined and depopulated land—a scenario quite commonly found in Soviet military literature.

Such near-total annihilation is hard to envisage, although it would be irresponsible for anyone to ignore the possibilities. But what seems more likely, given the Soviet achievement of effective superiority, would be the crumbling of American resistance either after a limited Soviet nuclear strike or simply under a threat against which the United States would have become practically defenseless.

Military occupation, perhaps under a gradual and partially camouflaged facade, would be inevitable. And, however done, this would be accompanied by a slow but total Sovietization of America. [17]

Initially American surrender might not be given such a harsh name. America would be allowed to save a certain amount of face—whether it had to back down because of Soviet superiority of weapons or because it had lost an actual war—by disguising the unpleasantness of formal surrender under some such rubric as a “disarmament agreement.” America would agree to the dispatch of Soviet “inspection teams” to monitor the “agreement.” The teams would be military and would set up bases in key areas. Their consistent and rapid reinforcement, which the United States would be powerless to halt, would naturally lead, without undue loss of time, to full-scale Soviet control.

In the case of the three small Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, which were once democratic republics, the Soviets began their expansion by demanding “defensive” bases. This was done in the guise of a “military defense pact.” Ostensibly, this in no way intruded on the sovereignty or independence of the host countries. Within months, however, the Russians announced the discovery of “plots” against them, which required the total occupation of the states in question. A few weeks later “elections” were held, which not surprisingly resulted in a call for immediate annexation to the USSR. Each country was then placed under a special Soviet commissioner (one of whom was the veteran Mikhail Suslov, prominent in Moscow’s councils until his recent death) and under a Soviet police chief. Between them they introduced the full rigor of the Communist system.

On the other hand, in Poland and most of the other countries of Eastern Europe, when the Russians took over during the heavy fighting in the last phase of World War II, they thought it best, instead of imposing their own system immediately, to set up transitional governments in which representatives of the old political parties—with all “anti-Soviet” elements removed—were permitted to serve until such time as it became expedient to suppress them. In each case the Russians made sure from the [18] start that their Communist stooges controlled the police apparatus and all the machinery of repression. This is the likely pattern in the U.S.A.

The initial harshness of Soviet conduct in these circumstances depends on tactical considerations. At the moment, the Russians behave more roughly than they did ten or fifteen years ago but not as roughly as they did thirty years ago. They are still somewhat sensitive to presenting too repulsive an appearance to international audiences. But when the world is looking the other way (as to some degree in Afghanistan today), or during wartime, or in the turmoil of postwar circumstances, or when the globe has been sufficiently communized, complete ruthlessness has been and will be the order of the day.

If, in a few years’ time, the occupation of the United States actually comes about, it will mean that any significant, freely informed world opinion will have ceased to carry weight. There will be almost nobody left to placate or gull or shock. Any inhibitions on tough behavior by the Soviet troops, police, or bureaucrats who occupy the United States will not be applicable. The Russians will behave as they like, according to their estimate of the comparative benefits of actual ruthlessness and apparent concession.

Is it possible to imagine a smooth acceptance of the fait accompli by a people so spirited and freedom-loving as the Americans? We would naturally expect that there will be much resistance, at least of a sporadic and disorganized nature. Individual citizens or the remnants of defeated army units will inspire desperate revolts, riots, strikes, and demonstrations against the incoming occupier. These will be savagely stamped out and will be followed by rampages of terror, looting, and rape by the Soviet troops.

This is not to say, in spite of the immediate suffering it will cause, that such hopeless resistance will not be of value to the country as a whole. It will serve to offset the demoralization of an [19] America that has been defeated or goes down without fighting. It will inspire those who will eventually begin to work and plan for the liberation of their country. Many of the early resisters will, moreover, in any case, be men who are bound to be rounded up and shot by the Russians in any case, and who will decide that it is better to die in a foxhole, fighting back, than in the cellars of the secret police after months of suffering.

Random shootings, homicidal incidents, executions—either of hostages or as a result of mistaken identity—and so on, will anyhow certainly be major problems for Americans. Even if the occupation has taken place in more or less peaceful circumstances and the Soviet army has been largely kept in hand, many acts of violence will inevitably occur.

Misunderstandings will arise because of the simple fact that most Americans do not speak Russian and most Russian soldiers do not speak English. There will be little means of communication except by means of fist and rifle butt. Another difficulty will arise because many Russians are heavy drinkers. Most American cities are well provided with liquor stores, and most American homes are well stocked with bottles. Drunken soldiers are not easy to cope with. They will be further elated by the enormous scope of their victory.

What are you, the ordinary citizen, to do?

Your best course is to lay in, as far in advance as you can, an ample supply of provisions (see chapter 4). In the first days of the occupation keep off the streets. Stay indoors. Keep away from the windows. Remain at the back of the house. Do not reply to any knock on the front door. If you hear your front door being broken in, try to smuggle your family out of an exit at the rear if you can do so without running into any patrols that may be prowling in the back.

You will, of course, be able to recognize members of the Soviet army by their uniform. Should you by some mischance encounter them in the open air or on the sidewalk, stand aside, or step off [20] the curb, and keep your eyes down. Do not attempt any kind of heroics or dumb insolence. Russians are not famous for their sense of humor, and what sense of humor they possess is notoriously capricious. Take no liberties. These are mean people. In particular secret police troops—of whom there will be many—have done unspeakable things to their own countrymen, and there is no reason to suppose that they would not behave with a total lack of pity toward conquered Americans.

Judging by past performance, rape could be a major problem. Even if your city or area has been taken over without resistance, for the first three or four weeks you should expect massive and repeated incidents to occur. The women of your family should avoid letting themselves be seen outside the house or at the windows, if this is at all possible. Emergency hiding places should be provided for each of them in case of break-ins. As a precaution, we suggest that all the women in your family, from puberty to menopause, should begin to take the pill regularly when a Soviet occupation looks probable or even possible; in these circumstances, be prudent and lay in a sufficient stock. Women who are younger or older will not, of course, need such protection against unwanted pregnancy, although they will not thereby be exempted from the possibility of rape.

The usual procedure is for groups of five or six soldiers, or sometimes more, to enter a house, hold the males at gunpoint, and rape the females. In some parts of Central and Eastern Europe, the man of the house would attack the Russian intruders, and although he was killed, his action did result in a diminution of such assaults. Elsewhere in Europe the husbands and male relatives took the view that they would be needed later by their families and held themselves back. This led to less murder but more rape. Advice is difficult. The reaction will depend on the individual.

Note that a willingness to cooperate with the Soviet army does not carry with it immunity from rape. In Yugoslavia, local [21] Communists complained that some two hundred female secretaries of Communist organizations had been among the ravished.

You will have little defense against looting. If you go out, leave behind your watch or jewelry. It is even known for Soviet soldiers to demand jackets and shirts at gunpoint, so wear your oldest clothes. Remember that for these soldiers many things regarded as commonplace and as the everyday concomitants of American life will appear as new and marvelous. Looting of stores will probably be more general than the looting of homes; but you should be prepared for the latter. Hide anything of value, or anything you are going to need in the dark days ahead, if it is in any way possible to do so.

Incidentally, it is unwise to complain of looting or rape to the military authorities. It will do no good and may get you listed as a troublemaker. Moreover, in the ensuing period, the secret police will regard as particularly suspect anyone they know who has suffered at the hands of the Russians and who is hence likely to be an “unfriendly element.”

It will not be the aim of the Russians to annihilate the American people but, rather, to reduce them to the status of loyal, or at least submissive, subjects of the puppet regime in Washington. The full rigor of the system will not be put into effect all at once; there will be no immediate Sovietization.

While ruthlessly suppressing open opposition and ensuring complete control of the police, the secret agencies, and all armed bodies, they will maintain a democratic facade, at least over a transitional period of several years. Under this cover, they will introduce the major changes in the social and economic order in a piecemeal manner with the grip gradually tightening.

After the first troubled months, there will thus be an interval when things seem to be cooling down, when there is some [22] semblance of a return to “normality,” when things appear to be at least tolerable and even “not so bad.”

On the political side, the Soviets will promise that there will be no intention to interfere with, or even seriously to tamper with, the operation of American democracy.

In fact, it is probable that the first government following the American surrender will not even contain any open Communists. It will be a “coalition” of surviving Democrats, Republicans, and “Independents”—the latter being known as well disposed toward the USSR, but no more. In principle, the parties left in existence, purged of all anti-Soviet elements, will be designed to harness, as far as possible, the political energies of the various sections of the population. The new government will not even term itself “socialist,” but will proclaim itself “democratic” in the old sense, as was done in most of Eastern Europe.

On what kind of people will the Russians rely at this stage of the occupation? Experience shows that in the moment of defeat, it is usual, however one may detest the enemy power, to place a good deal of blame for the disaster on one’s own former government. Therefore, important politicians of quite honest character will be found who will have maintained, sincerely and over a long period, that the fatal confrontation with the USSR was America’s fault. They will assert that America has brought the catastrophe upon itself, and they will in consequence claim that it is their moral duty to make the best of a bad job and ensure that some sort of American government continues. This was the position taken by many Frenchmen (whose basic patriotism was unquestioned) who chose to remain with Pétain and Vichy in 1940 instead of crossing the English Channel and joining de Gaulle and by many honest Eastern European democrats when Stalin’s troops arrived. It is a genuine moral dilemma.

Such people will in effect assist the Russians in their [23] immediate aim of securing a government temporarily acceptable to Moscow without, at the same time, being too repulsive to the people of the United States. In any case, stunned by calamity, Americans will scarcely know which way to turn.

We should also mention, not only the outright Quislings and Husáks, but the host of opportunists and eager collaborators who customarily come crawling out of the woodwork in such crises and often from the most unlooked-for directions. A few at least will turn out to have been long-term and devoted Soviet agents all along. This you will only learn years later when they write their memoirs and boast about the matter. Such self-revelations were made by several leading political figures in Eastern Europe, for example, Fierlinger in Czechoslovakia and Ronai in Hungary. Outwardly genuine Social-Democrats, although secretly Soviet agents, they rose high in the councils of their party with Russian support. They later went on record about the way in which they eventually got control of their parties and then dissolved them into the local Communist parties.

Blackmail, often of the crudest sort, will also be used in suborning the loyalties of politicians. Those politicians (and other public figures) who have something in their lives that they wish to conceal, and that has been discovered by the KGB, could be pliable instruments during the period of transition. Such men, who would not betray their country in wartime, not even to save their own reputations, may probably now be able to persuade themselves, under KGB prompting, that they can be “moderating influences.” In Eastern Europe a number of “Agrarian,” “Social-Democrat,” and other figures of eminence were found to have been involved in financial or sexual scandals that the Soviets authorities kept quiet in exchange for their collaboration. The cases of Tonchev and Neikov in Bulgaria come to mind. In Western Europe, major leaders like Jouhaux, head of the French trade unions, and various other socialist and [24] union figures in Britain and elsewhere, became puppets of Soviet blackmail and were compelled to steer their organizations in a direction indicated by the Communists. There are certainly some American figures who would be susceptible to such tactics.

In every sphere, people whom the Soviets consider useful as tools during the transitional era, even if they do not regard them as entirely trustworthy, will emerge. However, if you are considering a career as a collaborator, it is well to recollect that the Soviets are short on gratitude and that, as in Eastern Europe, within half a dozen years, the initial group of Soviet cat’s-paws is bound to vanish, almost without exception, in decidedly sticky circumstances.

Meanwhile, the “new” American government, containing familiar and even respected faces, will give the appearance of constitutionality and the reassurance of continuity.

This appearance of constitutional continuity will involve a flurry of “by-elections” to fill the seats that have been vacated by men who have been executed, who have fled the country, or who have resigned in despair. The new candidates will be hand-picked by organizations that have already been purged of their “anti-Soviet” elements. Those likely to present an image of sturdy independence will be discouraged from presenting themselves as candidates by various effective means. The counting of the votes in such elections and by-elections will be done by committees selected with special care.

By this means, Congress and state and local bodies will be largely transformed into organs that offer no effective resistance to the consolidation of the new order. Even so, at first there will be men and women, even among the newly elected, who will begin to voice objections. They will be attacked in the media, harassed, and left for removal until the next “elections,” by which time the whole political process will be under complete control and no awkward-minded senators or congressmen will remain to inconvenience the government. This will result in a [25] wave of show trials in which the objectors will be charged with conspiracy to overthrow the government.

The death or deposition of the president and vice-president, assuming that they have not managed to flee the country, will be handled in the same way. Possibly it might not be necessary to execute or even depose them, at least at first; compromised by the responsibility of signing the instrument of surrender, they might prove to be acceptable figureheads during a brief transitional phase. They could of course be forced to resign or be impeached by a pliable Senate and replaced, in the manner provided for in the American Constitution, by a Speaker newly elected by a much-changed House of Representatives. But there might be time enough to get rid of them when the regular presidential election year arrives, when the outward appearance of traditional practice would be maintained.

The main thrust of the Russians will, of course, be behind the Communist Party of the United States. It will be confronted with a formidable task of organization. It will be given all the money, premises, and access to the media it requires and some control of security and other armed groups. Initially it will attract a swarm of recruits in the shape of careerists, but as an obvious stigma will attach to it in the minds of most Americans, it will quickly seek to expand itself by other means as well. After a short interim period, for example, it will attempt to merge with other organizations of the Left into a “united party” under effective Communist guidance. At this juncture, what you will probably see is a “Unity Congress,” with a Socialist party splinter group pretending to be the entire party, a similar pseudorepresentation of the American Labor party based in New York, and a revived Farmer-Labor party, all funded and controlled by the Soviets and stiffened with Communist cadres. In addition any New Left groups that had previously been identified in any way with Leninism will be represented. Soon a merger between all these Leftist groupings will be arranged, under the name of the now fake [26] Farmer-Labor party or the equally fake Socialist party. In this way a respectable-looking basis for establishing a third major party under total Communist control would be provided, and the new party would enter into a “coalition” with the remains of the Democratic and Republican parties and gradually work toward dominating the whole state apparatus.

To begin with, the American Communist party will necessarily find itself somewhat shorthanded. We should note that, even on official figures, the Romanian Communists numbered only a thousand in a country of eighteen million and were nevertheless a mass party, in total control, with the usual set of puppet democratic parties only holding a few decorative posts, within a year of the arrival of the Soviet army.

It is of course not the case that there will be thousands and thousands of Americans who are suddenly converted to communism or show themselves to have been unsuspected sympathizers of it all the time. It will simply not be possible for the new rulers to operate entirely, or even to a very great extent, through the sort of people they would wish to have in charge. They will work, instead, through the careful establishment of Communists and others prepared, for whatever reason, to do their will in a comparatively limited number of key posts.

From these they will enroll, as far as possible, a broader section of the population, including those who have any favorable opinion whatever of the Soviet system or of its replicas in Vietnam and elsewhere and even of those who merely dislike the American system as it was before the Occupation, together with the unscrupulous and the ambitious.

It has been reckoned that, in any population, about 2–3 percent of the people in the country will be ready to carry out, for power and payment, the most revolting tasks that any regime whatever wishes to perform. The Communists could therefore certainly look forward to about a couple of million persons to staff their operations. This is a smallish number, but on the [27] record of other countries, it will be found enough (with Soviet help) to provide a just adequate framework for administering and controlling factories, schools, offices, and municipalities.

Their control will be spread thin at first and gradually strengthen. If you are not favorably inclined to the new regime but have passively accepted it out of apathy or inability to see any alternative, you may find yourself a manager, school principal, or whatever. But you should note that your prospects of longer tenure are low.

Even when, by such methods, the Communist party has expanded to its maximum, membership will not be granted to all who wish to join. There comes a point at which the party is big enough to control the country and holds all the posts with even the slightest influence down to township level; then recruitment will ease off, and purging and discipline of the new membership will become intense (see chapter 5).

Under the party, as its youth subsidiaries, will be two much bigger organizations (already in existence), the Young Communist League and the Pioneers.

The Young Communist League will be extended to enroll millions of young people in their teens and early twenties, and membership will be a virtual requisite for a large number of jobs above the most menial. Its branches will be under the control of party members, and all Young Communists will be required to obey party orders, to attend indoctrination sessions, and to operate as an arm of the party in their schools, streets, and homes.

The Pioneers are a sort of ghastly parody of the Scouts and Guides and were consciously so right from the start. They will be virtually compulsory for all preteenage schoolchildren. The Pioneers will be subjected to a simple style of propaganda, be given many attractions, go to indoctrination-infested summer camps, and have various solemn ceremonies in which, for example, they dip their richly embroidered flags in the memory of Lenin and take oaths of loyalty to the organization and its aims. [28]

The whole apparatus of state legislatures, city councils, and so forth, will continue. But you will get used to the idea that the real power in your neighborhood is not in the hands of these officials but in those of the local party secretaries. Legislatures, including Congress in Washington itself, will meet less and less frequently until it is a matter of no more than five or ten days a year that they will be in session to unanimously pass bills laid before them by the Communist authorities.

As one of the principal agencies of restraint, the new government will be able to rely, of course, on a totally reorganized FBI—for it is possible that the old name will be kept, again for purposes of continuity, although behind the facade, the whole organization will have been virtually dissolved (and all operatives who have been concerned with preventing subversion or countering Soviet espionage are liable to be shot). If those present in the top echelons have the time and the opportunity, it is to be hoped that they have already made arrangements to destroy all sensitive files, in order that agents now working under cover may have some chance of survival. Similarly, the names and dossiers of left-wing but anti-Soviet activists, who might help to provide a nucleus of anti-Soviet resistance, should not be allowed to fall into the hands of the Russians, who are likely to be unprecedentedly thorough in their elimination of such persons.

In any case, the new secret police, whether called the FBI or not, will be staffed entirely by totally reliable Soviet agents and will be supervised by Russian “advisers” who will be vested with full authority. It will be enormously expanded and will be provided with its own paramilitary formations.

As for the all-important question of controlling the organs of public information, the suppression of a selected number of newspapers, magazines, television and radio stations will be “demanded” because they have been the organs of “warmongers,” and their premises and facilities will be delivered up to the Communist party. Other newspapers, magazines, television and [29] radio stations not placed immediately under Communist control will continue to appear for some time, provided they have purged their staffs adequately and can secure the raw materials and other necessities they require in a time of dire scarcity. But they will all, of course, be strictly censored to make sure that nothing anti-Soviet or antigovernment appears.

Within a matter of months, all modes of mass communication will retail no news or information except that which conforms totally to the pro-Soviet line. For years to come, you will read or hear nothing but dreary praise (full of falsified statistics) for the Soviet Union and for the progress made by the new United States. Entire editions and newscasts will be given over to the texts of speeches by Soviet dignitaries and their American followers. Authentic news will be largely absent, and what there is will be highly dubious. This boring mishmash will occasionally be enlivened by accounts of the trials of “war criminals”—American political and military figures accused of waging, or merely planning, war against the USSR. You should not be surprised to find personages for whom you entertain the greatest admiration confessing to barbarities of which you rightly believe them to be incapable. You must remember that they will have been in secret police hands for a minimum of several months.

In the absence of reliable printed or broadcast news, if you wish to remain well informed, you will have to rely on rumor and on foreign broadcasts. Needless to say, not all of the rumors will be true, and many will have been deliberately planted by the authorities.

You will have to develop a feeling for the plausibility or implausibility of anything you hear. Does it seem probable? Does it fit in with other information? Often you will have to suspend judgment until some later piece of information confirms or refutes what you have heard.

You should also develop the knack, common in all Communist countries, of expertly reading between the lines of the [30] official press. Attacks on officials of the Department of Agriculture, for example, taking them to task for mismanagement, probably presages a food shortage or even a famine. Particularly sharp concentration on the evils of China or some other foreign country may well imply that war is contemplated. And so on. You will become adept at interpreting the nuances of the official clichés.

Just as you must take great precautions when listening to foreign broadcasts (if you possess a set powerful enough to pick them up), so you must be very cautious, when it comes to unofficial information or rumor, of whom you listen to and to whom you pass it on. Merely to receive “hostile” information without reporting the “rumormonger” to the police is a criminal offense. To transmit it is worse. However, except in the case of news particularly offensive to the Soviet authorities, you should not encounter too much trouble if you are reasonably circumspect (unless the authorities are looking for some pretext to arrest you anyway). After all, almost everyone, including the local Communists and even the police, will have no alternative except to rely on, and subsequently to spread, that same material. They will live in the same fog that you do. [31]

2. IMMEDIATE DANGERS: PRISON AND LABOR CAMP

SOME OF THE dust, atomic or otherwise, of the conflict and its immediate aftermath has now settled, and the new administration has taken over your town. The first thing you should bear in mind is that you and your family will face a constant threat of arrest and disappearance either into the labor camps or into the execution cellars.

As we shall see, large numbers of Americans will be doomed to arrest, in any event. For the rest of the populace, it will be largely a matter of luck—although you can temper your fate, at least to some degree, by trying to understand the predicament in which you have landed and attempting to make a swift adjustment to it. We can by no means guarantee that readers of this book will be among the survivors, but at least, we offer some tips that might mean that their chances will be considerably improved.

Arrest

The majority of American citizens are patriotic, naturally [35] outspoken, and innately opposed to the idea of dictatorship. Many frank remarks will be made in the early months of the occupation that will very soon be bitterly regretted.

The Soviet authorities will not, of course, be able to arrest everybody, but since it will be necessary to repress and deter hostile thought and action, the number of arrests will obviously run into millions.

In a “difficult” country like America, where the tradition of liberty has been strong, the probability is that, apart from executions, about 25 percent of the adult population will ultimately be sent to forced-labor camps or exiled under compulsory settlement in distant desert and arctic regions or in the USSR. If past performance is anything to go by, around 5 percent of the prisoners in the labor camps would be women, although in a country like the United States, where women are so influential and play such a prominent role in the national life, the figure may be much higher.

In these circumstances, you will have given thought to the future of your children.

Sometimes, particularly in the early days, it will be usual for children to go to relatives should both their parents be arrested. If you have been unable to make such an arrangement in advance or no such relatives are available, the probability is that they will survive as members of gangs of urchins living on their wits, subject to arrest and incarceration in adult jails as soon as they are in their teens.

Later, State orphan homes, often barely distinguishable from reformatories, will be set up for such children. There they will be indoctrinated in Communist beliefs and, later, if suitable, sent to serve in the police and other units.

You should seriously consider how you can best equip your children for both spiritual and physical survival should they become lost or orphans. First, like yourselves, the rule is to be fit, [36] not fat. When things start to look menacing, your relations with them must be particularly warm and trusting for they will only have you to turn to in a world that is becoming filled with suspicion and hatred and where nobody can be expected to talk freely and honestly. You will have to balance the necessity of never saying anything that they might innocently blurt out in front of unreliable acquaintances or known agents of the regime, against the need to ensure that their basic attitudes towards their country, their religion, and their parents remain as firm as is possible. It will be difficult for you and equally difficult for your children. But remember that experience shows that, on the whole, children remain loyal to their parents’ teaching and example long years after the parents themselves have vanished. They will adapt very quickly to the new conditions and learn how to keep their real attitudes concealed while conforming outwardly to the official cult. With younger children, on the other hand, it may be that they will forget their parents completely. Even so, when they grow and find out for themselves what the real nature of the regime is, any seed you may have planted of a positive kind may still be there, ready for events to help it flower. In Soviet-occupied countries, it has been the young who have formed the core of mass resistance whenever that has become feasible.

You can only do your best, and hope and pray for their future. If you are lucky, and survive, it may even be possible for you to trace your lost ones and, against all the odds, be united with them in fifteen or twenty years’ time.

The first wave of arrests and deportations will be inflicted not on the ordinary citizen but on outstanding and major figures, who will be seized as “war criminals.” They will include political leaders and military men with a record of urging or heading resistance to communism in the international sphere. [37]

The next wave, more gradual and broader, will extend to community leaders of every sort, particularly those who may have had any kind of international connections through travel, correspondence, or in the course of business. We might quote the official Soviet list of people subject to what was officially termed “repression” in the Baltic states when they were Sovietized. Among the various categories were the following:

- All former officials of the State, the army, and the judiciary

- All former registered members of the non-Communist political parties

- All active members of student organizations

- Members of the National Guard

- Refugees (from the USSR)

- Representatives of foreign firms

- Employees and former employees of foreign legations, firms, and companies

- Clergy

- People in contact with foreign countries, including philatelists and Esperantists

- Aristocrats, landowners, merchants, bankers, businesspeople, owners of hotels and restaurants, and shopkeepers

- Former Red Cross officials.

Since the danger of arrest is therefore substantial, whether you are “innocent” or not, we would advise you to be prepared for it at all times.

If arrested, you will probably be allowed to take a small package or a small suitcase with you, although all portable goods will eventually, with the connivance of the transport guards or camp guards, be stolen from you. (If you are merely being deported into exile and forced to reside in distant parts, you may even be permitted to take up to fifty pounds of baggage, although this too will be liable to theft.) However, it is always [38] sensible to have bags packed and ready, so that you are not taken by surprise. At least compile a list, in order not to omit some essential item in the confusion of arrest. And, summer or winter, always keep a couple of pairs of good solid shoes and several pairs of socks handy. A quick-witted wife has often saved her husband’s or son’s life in Communist countries by keeping shoes, socks, gloves, scarf, and a warm overcoat handy. Remember that, if you can manage to hang on to them, minor articles of clothing can also be exchanged later for a loaf of bread in case of extreme need in prison or camp or on the journey there.

What pattern can you expect your arrest to follow?

We quote a typical official instruction from the Baltic states, although this applies to the arrest and deportation of whole families:

Operations shall begin at daybreak. Upon entering the home of the person to be deported, the senior member of the operative group shall assemble the entire family of the deportee into one room. It is also essential, in view of the fact that large numbers of deportees must be arrested and distributed in special camps or sent to distant regions, that the operation of removing both the head of the household and the other members of his family shall be carried out simultaneously, without notifying them of the separation confronting them.

If you refuse to answer the door or to open it, it will be broken down. The operatives may or may not be provided with “search” and “arrest” warrants, but if they are, these are likely to be of a perfunctory and reusable variety. If the intention is to subject the arrestee to a propaganda show trial, as is occasionally the case, “evidence” will be planted on him or on the premises (like the one thousand German marks and one hundred American dollars planted in a cupboard of Ginzburg’s apartment when he was arrested in January 1977). [39]

What will happen to you when you have been taken to prison in a car, van, or truck?

First, you will be taken, after being briefly booked, straight to a prison cell. This could be in an improvised building, since the local prisons may be full to overflowing. You must not expect to enjoy the amenities of everyday American prison existence, where only a handful of men are placed in a single cell.

In the first great waves of mass terror, the crowding in prisons will be terrific. In the Soviet Union, it is common to read of from 70 to 110 people in cells designed barely to hold 25. When the overflow gets too great, it is likely, as in Soviet provincial towns, that vast pits will be dug and roofed over and prisoners simply herded in.

Washing will be a problem. For example, 110 women in one cell were allowed forty minutes with five toilets and ten water taps. The diet and general conditions will be unhealthy; prisoners will show a peculiar grayish blue tinge from confinement without light and air. Dysentery, scurvy, scabies, pneumonia, and heart attacks will be common and gingivitis universal.

Traditionally, on first arriving, you will find yourself occupying the spot next to the sinkhole or slop pail, but in the course of time, as the previous prisoners are taken out, you can expect to move up to a superior location.

At this stage of your incarceration, your wife, if she is able to find out where you are, will be allowed to come to the prison (though not to visit you there) in order to pay over small sums to the prison authorities with which, if they reach you, you may be able to buy such items as cigarettes and sugar. She may also be allowed to hand in packages of food and clothing.

You must do your best to adjust to the chaotic conditions and to accustom yourself to the fact that your prospects of release are almost nonexistent. You will have been considered guilty from the very fact of your arrest. Resign yourself to being held for an [40] average length of time of from one to three months in your present situation.

Interrogation

You will be required to make a confession to one or more crimes against the State.

The Soviet secret police use three main methods to obtain confessions. If you are, as is unlikely, important enough to be marked down for a show trial, the long-term system of breaking your personality, which has become known as “brainwashing,” will be applied. This involves a minimum of about three months with every possible physical and psychological pressure, especially inadequate food, inadequate sleep, inadequate warmth, and constant interrogation. Evzen Loebl, one of the Czech prisoners who confessed in the notorious Slansky trial and had the luck not to be hanged, describes having to be on his feet eighteen hours a day, of which sixteen were under interrogation, and during the six-hour sleep period having to get up and report every ten minutes when the warden banged on the door. After two or three weeks, he ached all over, and even washing became a torture. Finally, he confessed and was allowed food and rest, but by this time, as he put it, “I was quite a normal person—only I was no longer a person.”

The chances are, however, that you will be made to confess by more time-saving methods. These are (often in combination) beating and the “conveyor” (that is, continuous interrogation without sleep for periods up to five or six days).

These methods are not infallible, and there have always been a few prisoners whom they did not break (and many more who, although confessing under these pressures, repudiated the confession when they recovered.) [41]

As for the effects of beating and torture, we recommend the accounts by American prisoners of war in Hanoi, who were regularly tortured to betray the means of communication set up between them. There is a limit to almost anyone and no need to be ashamed if you give in.

Advice is difficult. Nevertheless, your chances of saving your life will be improved if you firmly decide not to confess to a capital offense. Interrogation machinery will be severely stretched, and it may be that your interrogator, to save time, will accept a confession of some lesser crime like “anti-Communist propaganda,” which will only earn you five to eight years in a labor camp if you hold out long enough. Never, under any circumstance, believe promises that if you confess to capital crimes, you will be reprieved.

Your other problem—this time one of conscience—will be that you will be asked to name “accomplices.” Try to use names of people you know are dead or have escaped the country or otherwise disappeared. In addition, you may be able to involve Communists or other Quislings.

You will eventually be sentenced, though not necessarily in your own presence—the judgment may merely be a smudged form handed you by a warden. Then, assuming you have avoided execution, you will be packed off to a labor camp.

Labor Camps

The trip, in tightly sealed cattle trucks, may last some weeks; and since the labor camp system will at first be more or less unorganized, you are likely to find that you and your companions are simply dumped, in the heat of the summer or the cold of winter, in a wooded area, where you will forthwith be set to work to build your own camp. Meanwhile you will live in a pit dug in the ground and covered with a canvas sheet. [42]

One of the most likely sites for a great concentration of labor camps is in the uranium-bearing area of the Canadian Northwest Territories. There, as in similar projects in the USSR, climatic and other conditions are so hostile that it is hard to attract free labor except by the payment of astronomical wages. In America, too, the Soviet authorities will be able to draw upon an inexhaustible supply of forced laborers. Forced labor will also be employed in other areas of difficult exploitation or where massive unskilled labor is advantageous (for example, in working the oil-bearing shale beds of the American West). We can also expect forced-labor battalions to be put to work in Greenland and, in particular, in exploiting the coal and other deposits of Antarctica, where Soviet rule is likely to have been established by default. If, as is often stated, these deposits prove to be immensely rich, we may expect hundreds of thousands of American prisoners to be sent to work them, with the added advantage that the prisoners’ whereabouts will be quite unknown at home. Conditions there may be expected to be extremely adverse, the work exhausting, and the prospects of survival negligible. Northern Canada, where the death rate will be high by all normal standards, would be a Utopia in comparison.

Uranium mining, however unpleasant, is at least rational. Many of you will find yourselves wasting your lives on projects whose only justification is the grandiose self-importance of political leaders or planners. For here, as everywhere else in the Soviet-type “planned economy,” there will be enormous and idiotic waste. In the Soviet Union, a quite unnecessary and uneconomic Arctic railway to the town of Igarka was labored at for four years in temperatures down to −55° Centigrade in winter, by scores of thousands of prisoners in more than eighty labor camps, at intervals of 15 kilometers along the 1300-kilometer stretch. In the end, only 850 kilometers of rail and of telegraph poles had been built, and then the line and signals, the locomotives, and everything else were abandoned to rust in the snow. In [43]Romania, hundreds of thousands of prisoners’ lives were lost in the Dobruja marshes, building a grandiose “Danube-Black Sea Canal” that was similarly abandoned. And there are many lesser tales of wasteful and useless projects dreamed up by stupid careerists trying to make a name. It will be little consolation to you to know that, when such a project fails, its originator may not be able to escape the search for scapegoats and end up in a camp himself or even be shot for “sabotage.”

Wherever you are sent, you will find yourself working up to sixteen hours a day, from the 5 a.m. reveille, ill clad and undernourished. Even today, in the peacetime USSR, labor-camp ration scales are well below those issued by the Japanese in the notorious prisoners-of-war camps on the River Kwai (which averaged 3,400 calories a day against the Soviet 2,400).

How are you to prepare yourself for this?

If you at present perform a desk job or follow some other sedentary occupation, it is vital that you make yourself fit and ready for hard manual labor. In all the Communist countries, it has always been found that professors, lawyers, administrators, and officials are among the first people to succumb in the labor camps, where they are suddenly faced with intense physical exertion on inadequate rations.

You might also begin to practice a few skills that might possibly save you, once you are in the camps, from the most burdensome and debilitating work. For example, you might be able to stay alive if you were to take a first-aid course since you could then become a camp medical orderly or nurse. Doctors, subject to the limitations that will be noted later, would enjoy an automatic advantage. A few other professions might prove similarly beneficial. If you are an artist, for instance, the staff of the forced-labor camp will possibly employ you for such tasks as [44] painting the numbers on prisoners’ jackets, and so on, while senior camp officials have often been known to award painters a higher ration in return for paintings to decorate their quarters.

There is one problem that we ought to mention that will concern the relatives of the people who have been arrested. It is this. They are likely to find themselves approached by the secret police with the proposition that they will gain better treatment for the arrested member or members of their family, or perhaps even save them from execution, if they will become police informers and report on the work and private life of their friends.

When this happens, it will present you with a nasty moral dilemma. All the same, it might help you to bear in mind that such promises to ease the lot of arrested relatives have never, in Communist countries, been honored. In any case, the local branch of the secret police will have no control over what goes on in a labor camp hundreds, or even thousands of miles away. Once in the camps, your relatives are in a different world, almost on another planet, and beyond your ken.

Allied to this will be a further ordeal, affecting all rather than merely the closest relatives of the arrested person. Once your husband (for example) has been found guilty and sentenced as an enemy of the people, you, as his wife, together with your children, will be required to repudiate and denounce him. At school, your children will be required to go up and stand beside the teacher’s desk and make a public condemnation and repudiation of their father. This is standard practice everywhere in Communist countries.

In the early phases, when the grip of the occupiers is being tightened to the limit, or after rebellions or other crises, the maximum Soviet terrorist methods will be used. At other times, there may be comparative relaxation. Perhaps we should give you some examples from the present situation in the Soviet [45] Union, when the country is at peace and wishes to avoid making a bad impression in the Western world.

In June 1977, a group of former Soviet prisoners who had managed by one means or another to reach safety in the West gave evidence at a hearing that was conducted at the Institute of Physics at Belgrave Square in London. The hearing was trying to accumulate evidence that might eventually assist in the case of Professor Yuri Orlov, a Soviet physicist who had been arrested in February 1977 on unspecified charges and was being held without trial. Extracts from the hearing were later published in the journal Index (November-December 1977).

Among those who testified were former inmates of (1) a Soviet prison, and (2) a Soviet labor camp.

Let us allow Vladimir Bukovsky, who underwent his most recent spell of incarceration in the Vladimir prison, to speak first.

I am 34 years old. I have been arrested four times because I expressed opinions which were not acceptable to the Soviet authorities. In all I have spent more than eleven years in prison, camps and psychiatric hospitals.

I spent a long time in Vladimir prison. The normal cells there have iron screens on the windows so that no ray of light can penetrate. The walls of the cells are made of rough concrete so they cannot be written on. They are damp. There is a heating system, but part of the punishment is to keep it deliberately low even in wintertime. The guards shove food through a trap door.

Sometimes the cells have no lavatories at all, only a bucket. Sometimes there is just a hole in the floor without any separation from the sewage system: all the stench from the sewage system thus comes back inside the cells, which have no proper ventilation system.

In punishment cells the conditions are worse. You are kept in solitary confinement in a room which is about 24½ sq.m. The only light is from a small bulb in a deep niche in the ceiling. [46]

At night you sleep on wooden boards raised a few inches off the ground without any mattress or blankets or pillow. You are not allowed to have any warm clothing. Often there is no healing at all in winter. It is so cold that you cannot sleep, you have to keep warm by jumping up and running around your cell to keep warm.

At 6:00 o’clock in the morning your wooden bed is removed and there is nothing for you to do for the rest of the day, no newspaper to read, no books, no pen or pencil or paper-nothing.

According to the regulations a prisoner can only be put in solitary confinement for fifteen days, but quite often when one fifteen-day period ends prisoners are put back in for another fifteen days. I was lucky, because although I was in solitary confinement several times, I only had fifteen days at a time. Others were not so fortunate. It is quite customary for people to spend forty-five days in solitary.

In solitary confinement prisoners get a specially reduced diet. This is part of the punishment which I received in Vladimir prison in 1976 after Mr. Brezhnev had signed the Helsinki Declaration. On alternate days I had nothing to eat or drink except a small piece of coarse black bread and some hot water. On the other days I had two meals—in the middle of the day—some watery soup with a few cabbage leaves, some grains of barley, sometimes two or three potatoes. Most of the potatoes were black and bad. In the evening I had gruel made from oatmeal or some other cereal, a piece of bread and several little fish called kilka, which were rotten. However hungry I was, I could not eat them. That was all.

The shortage of food, the poor quality of the food you are given, and the appalling living conditions mean that almost everyone who has endured imprisonment suffers from stomach ulcers, enteritis or diseases of the liver, kidneys, heart, and blood vessels.

When I was first arrested I was very healthy, but after I had [47] been in prison I too began to suffer from stomach ulcers and cholecystitis. This did not make any difference to the way I was treated. I was still put in the punishment cell on a reduced diet.

I was in the same cell with Yakov Suslensky, who suffers from a heart condition. He had a severe heart attack in an isolation cell, but was not taken out of isolation. He was moved, but only to another isolation cell. After he came out of isolation he had a stroke. This was in March 1976.

I was also in Vladimir prison with Alexander Sergienko who had tuberculosis. Notwithstanding this he was put in solitary confinement on a reduced diet.

I was also in prison with Mikhail Dyak, who suffers from Hodgkin’s disease. He was released early, but not until three years after confirmation of his diagnosis. I knew many other people who were not released even though they had cancer and other serious illnesses.

In prison you are allowed to send out one letter a month, but the authorities can deprive you of that. If prisoners try to describe their state of health or the lack of medical help in prison, their letters are confiscated.

In prison hospitals essential medicines are often not available. I remember in 1973 a man named Kurkis who had an ulcer which perforated. There was no blood available to give him a transfusion. He lay bleeding for 24 hours and then he died.

Next, we might take the experiences of Andrei Amalrik, who described what life is like in a labor camp.

The strict regime camp of Kolyma is 300 kilometres north of Magadan, where the winter lasts eight months and is very harsh: the temperature varies between 20 and 60 degrees Centigrade below zero.

The camp is surrounded by several rows of wire. Inside the wire are two wooden fences, and dogs patrol the space between them. The camp is divided into a living compound and a work [48]compound. In the living compound are four barrack huts accommodating eight hundred prisoners.

All the prisoners have to wear uniforms made of thin grey cloth and very thin boots. Everyone has their name and number sewn on their clothes. You march everywhere in columns.

Prisoners are fed three times a day. Breakfast is a sort of thin porridge, dinner is soup. Those who have fulfilled their work norm get extra porridge. The soup is very poor and has very few vitamins. That is why most of the prisoners are ill.

Prisoners work in the machine and furniture factories where the dust fills your lungs, or outside cutting wood and in the construction brigades.

It is difficult enough to work outside when the temperature is less than minus 20 degrees Centigrade; at minus 50 or 60 degrees the conditions are almost unimaginable. When it is as cold as that there is a sort of dry fog, which means that if you extend your arm, you cannot see your hand. Yet every day you have to go out and work (with the exception of only one day when I was in camp). It is so cold that many prisoners suffer inflammation of the ear, which can lead to loss of hearing. You are allowed to wear extra clothing or a fur cap. I made a band to go over my ears out of some socks, but the guards believed that I must be wearing this so I could listen to the BBC, which of course was nonsense.

I was put in a punishment cell on two occasions. Once in prison and once in camp. I was in a cell by myself. The cell was 1.5 m. wide and 2.5 m. long. The bed in the cell was made of wood. It was attached by hinges to the wall. In the daytime it was raised up and locked against the wall. The only thing to sit on was the concrete block on which the bed rested.

When I was put in the punishment cell my usual clothes were taken away and I was made to wear specially thin clothes. There were no books. You were allowed to smoke. I was given warm food only every other day and then it was of very poor quality. On the other days I just had bread and water.

In the punishment cell the heating was very low and there was a [49] window, but it had no glass in it, so that the intense cold came right into the cell. It was impossible to sleep. You had to keep moving about all night in order to keep warm.

I was lucky. I only spent five days in the punishment cells. The usual period was fifteen days. Frequently people spent fifteen days in the punishment cells, were let out for one day and then put back for a further fifteen days. Repeated solitary confinement means the slow destruction of the human body. Your personality is slowly destroyed.

Medicines are very poor and very few. In the camp

Date: 2015-02-28; view: 1356

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| What’s Left of Me | | | Worth_Jennifer_Call_the_Midwife |