CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

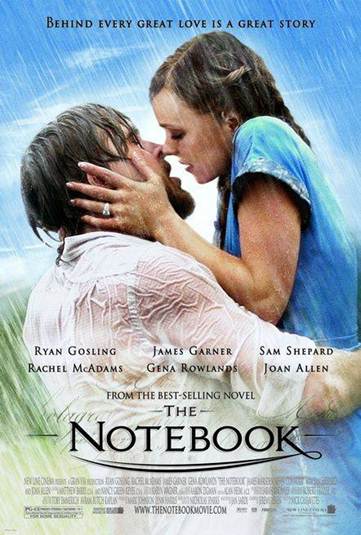

The Notebook

CHAPTER TWO GHOSTS

It was early October 1946, and Noah Calhoun watched the fading sun sink lower from the porch of his plantation-style home. He liked to sit here in the evenings, especially after working hard all day, and let his thoughts wander. It was how he relaxed, a routine he’d learned from his father.

It was early October 1946, and Noah Calhoun watched the fading sun sink lower from the porch of his plantation-style home. He liked to sit here in the evenings, especially after working hard all day, and let his thoughts wander. It was how he relaxed, a routine he’d learned from his father.

He especially liked to look at the trees and their reflections in the river. North Carolina trees are beautiful in deep autumn: greens, yellows, reds, oranges, every shade in between, their dazzling colours glowing with the sun.

The house was built in 1772, making it one of the oldest, as well as largest, homes in New Bern. Originally it was the main house on a working plantation, and he had bought it right after the war ended and had spent the last eleven months and a small fortune repairing it. The reporter from the Raleigh paper had done an article on it a few weeks ago and said it was one of the finest restorations he’d ever seen. At least the house was. The rest of the property was another story, and that was where Noah had spent most of the day.

The home sat on twelve acres adjacent to Brices Creek, and he’d worked on the wooden fence that lined the other three sides of the property; checking for dry rot or termites, replacing posts where he had to. He still had more work to do on the west side, and as he’d put the tools away earlier he’d made a mental note to call and have some more timber delivered. He’d gone into the house, drunk a glass of sweet tea, then showered, the water washing away dirt and fatigue.

Afterwards he’d combed his hair back, put on some faded jeans and a long-sleeved blue shirt, poured himself another glass of tea and gone to the porch, where he sat every day at this time.

He reached for his guitar, remembering his father as he did so, thinking how much he missed him. Noah strummed once, adjusted the tension on two strings, then strummed again, soft, quiet music. He hummed at first, then began to sing as night came down around him.

It was a little after seven when he stopped and settled back into his rocking chair. By habit, he looked upwards and saw Orion, the Big Dipper and the Pole Star, twinkling in the autumn sky.

He started to run the numbers in his head, then stopped. He knew he’d spent almost his entire savings on the house and would have to find a job again soon, but he pushed the thought away and decided to enjoy the remaining months of restoration without worrying about it. It would work out for him, he knew: it always did.

Cem, his hound dog, came up to him then and nuzzled his hand before lying down at his feet. Hey girl, how’re you doing?” he asked as he patted her head, and she whined softly, her soft round eyes peering upwards. A car accident had taken one of her legs, but she still moved well enough and kept him company on nights like these.

He was thirty-one now, not too old, but old enough to be lonely. He hadn’t dated since he’d been back here, hadn’t met anyone who remotely interested him, It was his own fault, he knew. There was something that kept a distance between him and any woman who started to get close, something he wasn’t sure he could change even if he tried. And sometimes, in the moments before sleep, he wondered if he was destined to be alone for ever.

The evening passed, staying warm, nice. Noah listened to the crickets and the rustling leaves, thinking that the sound of nature was more real and aroused more emotion than things like cars and planes. Natural things gave back more than they took, and their sounds always brought him back to the way man was supposed to he. There were times during the war, especially after a major engagement, when he had often thought about these simple sounds. “It’ll keep you from going crazy,” his father had told him the day he’d shipped out. “It’s God’s music and it’ll take you home.”

He finished his tea, went inside, found a book, then turned on the porch light on his way back out. After sitting down again, he looked at the book. It was old, the cover was torn, and the pages were stained with mud and water. It was Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman, and he had carried it with him throughout the war. He let the book open randomly and read the words in front of him:

This is thy hour, 0 Soul, thy free flight into the wordless,

Away from hooks, away from art, the day erased, the lesson done,

Thee fully forth emerging, silent, gazing, pondering the themes

thou lovest best,

Night, sleep, death and the stars.

Date: 2015-02-28; view: 1436

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| The Bird Woman | | | This New Science of Societies: Sociology |