CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Labor Legislation and the Growth of Unions

Before World War I, federal court decisions usually supported the rights of employers to fire or discipline workers for their union activity. They felt that workers banding together "restrained trade" in the same way that monopolies and big businesses operating together disrupted the operation of the marketplace. In 1914 the Clayton Antitrust Act was passed to define a variety of illegal business practices. Part of the law, however, made labor unions "exempt" from antitrust rules and regulations. Nevertheless, the courts continued to support the rights of employers over those of workers.

The 1930s and the Great Depression brought many changes to American life. Production fell to record lows and unemployment reached record highs. In an effort to revive the economy, Congress passed laws whose effects are still being felt. Among them were several that helped the growth of labor unions. The most important of these were the following:

• The Norris-LaGuardia Act of 1932. This law limited the ability of the courts to use injunctions-orders issued by a judge – in labor disputes. Injunctions were used mainly to stop workers from striking. Failure to obey an injunction results in a fine or imprisonment. The act also ended the use of yellow-dog contracts that required workers to promise they would not join a union.

• The National Labor Relations Act of 1935. Also known as the Wagner Act, the act guaranteed the right of workers to join unions and engage in collective bargaining. It also forbade employers from engaging in certain "unfair labor practices," and created a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to carry out the provisions of the act.

• The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. This law provided a minimum wage of 25 cents per hour and time-and-a-half for overtime beyond 40 hours per week. The minimum wage has been periodically increased. In 1991 it was increased to $4.25 per hour.

By the end of World War II there was a feeling that federal legislation had given labor so much power that it left management at a disadvantage. In an effort to restore the balance, Congress enacted the following laws.

• The Labor-Management Relations (Taft-Hartley) Act of 1947. The Taft-Hartley Act forbade employees from engaging in certain "unfair labor practices." It also outlawed the closed shop - one in which a worker must belong to the union to be hired. It permitted the union shop, which allows nonunion workers to be hired on condition that they join the union. Another provision of the act enables the president to obtain an injunction that delays for 80 days a strike that threatens "national health or safety."

Taft-Hartley also permits state legislatures to enact right- to-work laws. Now adopted in 21 states, these laws established the open shop by making it illegal to require a worker to join a union. Union leaders have long opposed the right-to-work laws on the grounds that they enable workers who have not paid dues to benefit from wages and privileges won by the unions at the bargaining table. Others, however, argue that it is contrary to the spirit of American free enterprise to require someone to join any organization as a requirement to hold a job.

• The Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959, also known as the Landrum-Griff in Act, sought to improve democratic procedures and reduce corruption within unions. The law requires that regularly scheduled elections of union officers be held and that the voting be carried out by secret ballot. Union officials are prohibited from borrowing large sums of money from the union, and the embezzlement of union funds was made a federal offense.

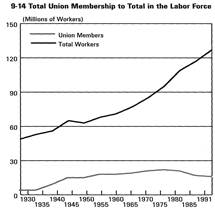

Approximately 17 million American workers belong to unions today. This represents a decline in membership from 36 percent of the labor force in 1945 to 13 percent in 1991.

There is little agreement why union membership has declined so dramatically. Some union leaders blame government, which they claim during the Reagan and Bush administrations had been hostile to them. They also cite the right-to-work laws as a factor in the declining fortunes of the labor union movement. Others argue that many businesses resist union organizing efforts and offer pay and benefits similar to those won by unions without union membership.

Some authorities stress the economy's shift from manufacturing to service as a reason for the failure of unions to recruit new members. Service companies are generally smaller in size than industrial firms and are therefore more costly for unions to organize. In addition, those who work for service firms have traditionally been more reluctant to join unions than have factory workers. Still, others argue that the reputation of the labor union movement suffered from the publicity surrounding the activities of a handful of corrupt officials and the illegal discriminatory practices of certain union locals.

Increased reliance on "contingent workers" to cut costs has also reduced union membership. Contingent workers are temporary, part-time, and freelance workers. Since they are treated as "independent contractors," they do not have tojoin unions, but they do not receive the same pay or benefits that union contracts secure.

Further, when large corporations relocate factories in areas where there are no unions or in foreign countries, union membership declines.

Despite the hard times that labor unions seem to be facing, they and their 17 million members will continue to be a major force in the economy.

Date: 2015-02-28; view: 1229

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| The Labor Movement in the United States | | | Union-Management Relations in Action |