CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Big Miracle: The real-life whale rescue which inspired new Hollywood blockbuster

For three weeks in October 1988 the world watched enthralled as rescuers fought to save three whales trapped in ice near the North Pole

With a cute baby whale, hunters, villainous bosses, Russian sailors, a band of eccentric animal-lovers and a healthy dose of Cold War drama, it had all the elements of a Hollywood blockbuster.

For three weeks in October 1988 the world watched enthralled as rescuers fought to save three whales trapped in ice near the North Pole.

The dramatic bid to free them brought together an unlikely band of allies – including whale-hunting Eskimos, environmentally-unfriendly oil executives, Greenpeace activists and a whale whisperer who reckoned he could scare them out using killer whale sounds.

Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev used the rescue to help thaw the Cold War, sending two huge icebreakers to help the American-led Operation Breakthrough.

Animal activists believe it helped change attitudes towards whales, especially among the Soviets who were then the world’s biggest whale hunters. Now, 24 years on, the story has finally arrived on the big screen.

Drew Barrymore stars in Big Miracle playing a gutsy Greenpeace leader who co-ordinates the rescue.

The role is based on the real-life experiences of environmentalist Cindy Lowry, a Volvo-driving vegetarian who risked frostbite rather than compromise her principles by wearing a fur wrap.

Cindy, who spent 16 years working for Greenpeace in frozen Alaska, got the first call from two Eskimo fishermen who spotted the three California Grey whales trapped beneath a thick sheet of ice five miles wide.

The giant creatures – nicknamed Fred, Wilma and Bamm-Bamm after the Flintstones cartoon characters – had to come up for air every four minutes but with just two small holes in the ice they had to take it in turns to breathe.

TV footage showing them bashing their bloodied heads against the encircling ice was beamed around the world.

Within 48 hours journalists from across the globe, including the Mirror, arrived in remote Barrow, one of the northernmost towns on earth, 320 miles from the Arctic Circle. They were joined by a bizarre array of would-be rescuers, including two brothers who had invented an ocean de-icing machine and Jim Nollman, who called himself an “inter-species communicator” and believed he could scare the creatures back out to sea by using recorded killer whale noises.

Cindy, now 62 and working as a marine preservationist in Portland, Maine, still gets tearful when she thinks about the rescue. “It was heart wrenching,” she says. “When we first flew out over the scene I wanted to be like Superman and just swoop down and punch my way through the ice to free them. I could tell the littlest one was already having a hard time. It was dreadful to watch.”

The story touched Drew Barrymore, whose character in the film is based on Cindy. Big Miracle, which opens today, was shot on location in Alaska and Cindy flew up there to advise Drew, 36.

“I first met her in Hollywood and spent time at her house,” says Cindy. “We had an instant connection.

“We both love dogs and care passionately about animal welfare. We’ve become really dear friends and kindred spirits.” Recalling her experiences during the rescue, Cindy says: “There was a story that I’d heaved in front of the world’s TV cameras when I tried a dip called Eskimo butter and discovered it was actually oil made from seals. That actually wasn’t true.

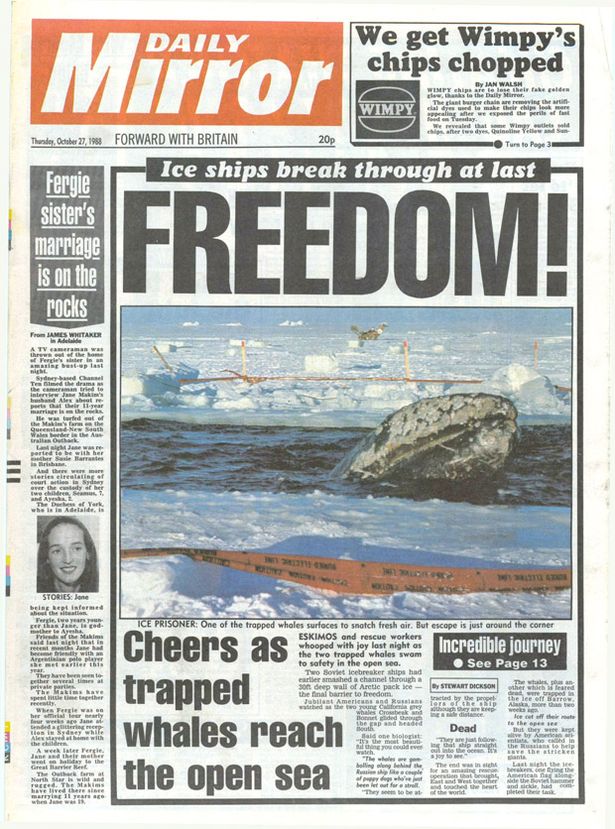

Front page: How we told of the rescue bid

Daily Mirror

“But I did refuse to wear a fur wrap someone offered me. I was perfectly fine in my wool cap, down coat and overalls. I’m delighted this movie has come out because it gets the message across that we still have much to do preserving wildlife and protecting the oceans.”

Drew, who shot to fame as the child star of ET and has carved out a career in romantic comedies like 50 First Dates and the Charlie’s Angels action flicks, has been helping get Cindy’s message about ocean conservation out while promoting Big Miracle. “We really clicked,” she says. “The thing I respect about Cindy is that she’ll go to extraordinary lengths to get her point across.”

Cindy’s campaigning skills were the driving force behind the rescue operation as she called everyone she could think of to help.

An oil company provided an 80ft long ice-breaking barge, which had to be dragged 230 miles across the frozen sea by two helicopters. When that got stuck, the chopper crews tried using a 10,000lb concrete and steel battering ram to punch holes in the ice.

And when all of the ice-chewing techniques failed, the Soviets offered help. As the rescuers waited, Inupiat Eskimos worked 24 hours a day with chainsaws trying to cut a path of breathing holes towards the open water.

But with temperatures below freezing and constant blizzards, the new holes iced over as quickly as they were cut. The rescuers tried de-icers to churn up warmer water on the sea-bed before using Nollman’s device to transmit noises made by much larger killer whales.

Cindy says: “That did the trick and they moved a little further out to new, bigger holes.”

But tragedy struck on the 14th day of the rescue bid when Bamm-Bamm, the nine-month-old baby who vets feared was suffering from pneumonia, failed to come back up for air. The whale’s body was never found.

Rescuers were loathing leaving the surviving whales alone after hungry polar bears lumbered across the ice towards them.

“Towards the end, I was out with both of them by myself,” Cindy says. “It was the middle of night and it was freezing. I think they could tell open water was close because they were livelier and swimming back and forth.

“I’d never touched them – though I’d often been close enough – out of respect for them and the struggle they were going through. But on this occasion I knelt down by one of the last air holes and one of the whales surfaced. I said something like, ‘Oh my, I think you’re going home’. He was just inches from me and rested his head on the ice and we just had this amazing, magical moment of eye contact.”

Cindy still gets tearful when she recalls that moment, just two days before the Soviet icebreaking ships finally ripped open a path and the whales disappeared into deeper water.

No one knows what became of them because they were not tagged. But Cindy is convinced the creatures, which can live to 70 and grow to more than 50ft long, survived.

She says. “A friend reported seeing two grey whales off Prince William Sound and all the other grey whales had gone by that point – so I think they made it.”

Date: 2015-02-28; view: 2157

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Bennett Laura - Didn't I Feed You Yesterdayi | | |