CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

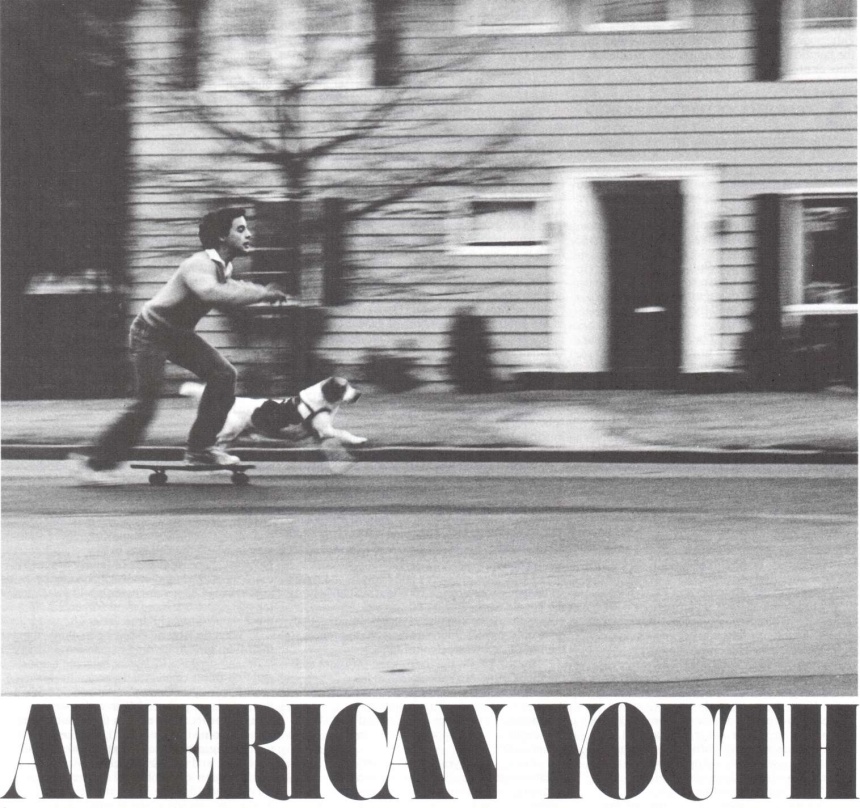

AMERICAN YOUTH

What is it like to be a young person in the United States?

At 18 years of age, young people in the United States can take on most of the rights and the responsibilities of adulthood. Before this occurs, however, the American teenager (a common name for a young person between the ages of 13 and 19), goes through the period of adolescence. Psychologists (specialists who study the science of human behavior) say that most young people experience conflict during this period of their lives. They are changing rapidly, both physically and emotionally and they are searching for self-identity. As they are growing up and becoming more independent, teenagers sometimes develop different values from those held by their parents. American teenagers begin to be influenced by the values expressed by their friends, the media (newspapers, television, magazines, etc.) and teachers. During this period of their lives, young people also begin to participate in social activities such as sporting events and church group projects, as well to do more things in the

company of members of the opposite sex and fewer things in the company of their families.

While the teenage years for most American young people are nearly free of serious conflict, all youths face a certain number of problems. Some young people have difficulties in their relationships with their parents or problems at school which may lead to use of alcohol or drugs, the refusal to attend school or even to running away from home. In extreme cases, some might turn to crime and become juvenile delinquents (a lawbreaker under 18).

However, for every teenager experiencing such problems many more are making positive, important contributions to their communities, schools and society. Millions of young people in the United States are preparing for the future in exciting ways. Many teenagers are studying for college entrance exams or working at part- time jobs after school and on the weekends. Others are volunteering at hospitals, helping the handicapped, exhibiting projects at science fairs or programming computers.

A LOOK BACK AT YOUTHS IN AMERICA

Imagine leaving your home, family and friends to come to a strange new country. That is just what many young people (sometimes with their families, but often alone) have done for more than 350 years in coming to the New World. For many immigrants (people who arrive in a new country), the New World offered hope of a better life; for all new arrivals, the change was traumatic.

In the 1600s, many children of poor European immigrants were apprenticed (contracted) to work without wages as servants for wealthier people until they were between 18 and 21 years of age.

Beginning in 1619, blacks were brought to North America as slaves to work for the few early European settlers. Young people as well as adults served as slaves until 1865, following the Civil War, when the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution was passed, which abolished slavery.

Later, the United States experienced major periods of immigration. The first occurred from about 1840 to 1880. During that time, most of the immigrants were from northern and western Europe. Most were fleeing poverty, or political or religious persecution. The second major period began in the 1880s. While immigrants still came from northern and western Europe, the majority now came from southern and eastern Europe, largely for the same reasons as the first group. Many found work in large cities such as New York, Chicago and Pittsburgh.

At the time of these major periods of immigration, children of all ethnic groups often worked long hours in factories, coal mines, mills or on farms. There were no laws regulating child labor until the 1900s.

However, many new Americans saw that education was their best chance for prosperity. In the 1900s, boys and girls began to attend schools in increasing numbers. Many stayed in school until they were about 15 years old. Work became less of an influence on young people. They were now being influenced more by their schools, churches and families.

At the beginning of the 1900s, new factories had been built, the western frontier was being conquered and the economy was growing rapidly. Though society still fell short of their ideals, youths—and their elders— believed that improvement and progress toward a better world was inevitable and unstoppable. The staggering shock and losses brought by World War I (1914-1918), however, caused disillusion. During the 1920s, youths in America determined to live life to its fullest in anticipation of an uncertain future, went "on the greatest, gaudiest spree in history" wrote novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald. Some young people tended to reject their parents' values and turned to the new jazz music, to dancing and to having a good time.

The Great Depression, beginning in 1929, put an end to this era. About 12 million people lost their jobs. Many people had a hard time

providing enough food for themselves. As a result, many children had to quit school to find work. Under President Franklin D. Roosevelt's direction, programs under the National Youth Service created jobs for many young people. Some three million young men took part in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), working to maintain forests and parks throughout the United States.

World War II (1939-1945) restored a feeling of national purpose and hope, and after the war the United States experienced the biggest baby boom in history. Extending into the 1950s, this increase in the birth rate produced the generation of young people known as the "baby boom" that reached adulthood in the 1960s and early 1970s.

During the 1960s, many youths met President John F. Kennedy's challenge: "Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country." They volunteered to help the handicapped, the poor and the needy at home and also in foreign countries through the Peace Corps. The decade of the 1960s was also a time of growing political awareness, turbulence and rebellion. On many college campuses, young people protested the country's involvement in the Vietnam War. They demonstrated and worked against racial segregation and against poverty. Some young people developed their own subculture, which included styles of dress, music and ideas about independence which were different from those of their parents.

Some women began calling for equality with men and developed the beginnings of what is now known as the women's liberation movement. Increasing discord in family life was openly discussed as divorce rates climbed and young people who couldn't agree with their parents' attitudes and values talked about the "generation gap."

Television programs and films introduced an unaccustomed openness about sexuality in the United States during this period. Many young people became involved in activities that once only some adults participated in, such as the use of drugs and alcohol.

By the 1970s, the times were different and the focus of youths' attention had been drawn elsewhere. Gone were the violent protests of the previous decade. The American involvement in the war ended and after military conscription was stopped in 1973, many protests died away.

In the 1980s, young people generally became more conservative and interested primarily in working toward success in their careers. One writer called the 1980s "the new age of realism." Others dubbed the young people of the 1980s "the me generation."

YOUTHS AND THEIR FAMILIES

The United States Census Bureau defines a family as two or more people who are related by blood, adoption or marriage, living together. Most American families include members of just two generations: parents and their children, though many extended families do include more than two generations. There are about 65.8 million families in the United States. What is the purpose of a family? Experts agree that the family structure should provide emotional, physical and educational support. The role of the family in a young person's life has changed in the past 100 years.

Families 100 years ago were large, partly because children were needed to work and earn additional money for the family. Now, young children no longer work and earn wages; in addition, providing an education and life's necessities for children is very expensive. As one result, American families are much smaller than in previous decades. In 1989, the average size of a family was 3.16 people.

In what types of families are children growing up? In 1989, the United States Census Bureau reported that while most families retain the traditional structure, including a father, a mother, children and sometimes a grandparent, 22 percent of all families with children under 18 years old are one-parent families (families with only a father or only a mother; the other parent not living with the family). Why? High divorce rates, separation and birth of children to unmarried women are a few reasons. In cases of separation or divorce of the parents, the parent not living with the children usually provides child-support payments. Most of the families in this category—five out of six—are headed by women. And one-parent families headed by women are usually poorer than other families. In 1989 the median family income in the United States was $32,191. For families headed by women, the median income was less than half—$15,346.

Some of these difficulties are relieved by government programs providing help to low- income families. One such program, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), helps poor parents with school-aged children. Another, the Special Supplemental Food Program for Women, Infants and Children, provides food to low-income women before and after childbirth. Still, poverty affects the way in which the children in these families grow up. Another change in family life is that more wives and mothers work outside the home. In 1988, women made up 45 percent of the national work force. And 65 percent of those women had children under 18.

What do American teenagers think about their families? According to a national survey taken during the mid-1980s, between one-half and two-thirds of all American youths have a "comfortable" or "happy" relationship with their parent or parents. Their traditional disagreements are over such things as: curfew (time to come home at night), whether or not to attend religious services; doing work around the house; and the friends with whom the young person spends his/her leisure time. A survey entitled, "The Mood of American Youth," published by the National Association of Secondary School Principals, also indicates that the majority of young people agree with the opinions and values of their parents.

STUDENTS AND THEIR SCHOOLS

The typical American student spends six hours a day, five days a week, 180 days a year in school. Children in the United States start preschool or nursery school at age four or under. Most children start kindergarten at five years of age.

Students attend elementary schools (grades one through six) and then middle school or junior high school (grades seven through nine). Secondary, or high schools, are usually 10th through 12th grades (ages 15 through 18).

In 1988, about 45.4 million students were enrolled in schools (elementary and secondary) in the United States. Students may attend either public schools or private schools. About 83 percent of Americans graduate from secondary schools and 60 percent continue their studies and receive some form of post-high school education. Approximately 20.3 percent graduate from four-year colleges and universities.

School attendance is required in all 50 states. In 32 states, students must attend school until they are 16 years old. In nine other states, the minimum age for leaving school is 17. Eight states require schooling until the age of 18, while one state allows students to leave school at 14.

How are American schools changing? The quality of education in the United States has often been debated in the course of American history. During the 1960s and 1970s, many schools offered a wide variety of nonacademic courses, such as "driver's education" and "marriage and family living." Educators were worried that students were not taking enough "academic" courses, such as mathematics and English. Many other reports soon came out with recommendations calling for stricter high school requirements.

In the early 1980s, the United States National Commission on Excellence in Education issued a report called "A Nation at Risk," reporting that "a rising tide of mediocrity threatens our very future as a nation." Educators were worried that students were not learning as much as they should. Scores on high school seniors' Scholastic Aptitude Tests (college entrance examinations) had declined almost every year from 1963 to 1980. "A Nation at Risk" also reported that 13 percent of 17-year-olds were functionally illiterate (unable to read and write).

Schools began to answer the challenge. Most states and school districts have passed new, more demanding standards that students must meet before they can graduate from high school. Most high schools now require four years of English, three years each of mathematics, science and social studies, one- and-one-half years of computer science and up to four years of a foreign language.

Business organizations, realizing that their future employees needed skills that could be learned in schools, pitched in to help. In Boston, for example, the business community offered jobs and scholarships to students who stayed in school to graduate. In other communities, companies "adopted" certain schools, usually in low-income areas, and provided tutoring, scholarships and other help. By 1988, there were 141,000 educational "partnerships." According to the U.S. Department of Education, more than 40 percent of the nation's schools and 9 million students are involved in some sort of partnership program. Corporations have also given grants to universities to improve teacher education.

Educators believe these and other methods to improve education are beginning to show results, and that U.S. schools are at least reversing the previous decline. Tests showed that student achievement in science and mathematics, which had declined during the 1970s, improved during the 1980s—although performance in reading and writing either declined or stayed the same. Average scores on the mathematics section of the Scholastic Aptitude Tests (college entrance exams) increased by a significant ten points between 1980 and 1990—although they were still substantially below the average in 1970. But scores on the verbal section of the test hovered around the 1980 level—more than thirty points below the 1970 level. Critics point out that U.S. students consistently score lower on academic tests—especially in math and science—than their counterparts in Europe and Japan. They believe the longer school year and more rigorous requirements in those other countries produce superior achievement. And they cite a study by the National Institute of Mental Health which showed that high school seniors had spent more time in front of a television screen (15,000 hours) than they had spent in school (11,000 hours).

High school students can take vocational courses that prepare them to perform specific jobs, such as that of a carpenter or an automobile mechanic. Advanced courses prepare other students for university or college study. Special education (for the handicapped student) is offered in most schools. Schools enroll about three million handicapped students.

At least 85 percent of all public high schools have computers. Students are writing computer programs and creating charts, art and music on computers.

Many parents are involved in working for better quality education in the United States. Parents are joining parent-teacher organizations, tutoring their children, raising money for special programs and helping to keep schools in good repair.

LEISIRE A!\D ACTIVITIES

Schools provide American students with much more than academic education. Students learn about the world through various school-related activities. More than 80 percent of all students participate in student activities, such as sports, student newspapers, drama clubs, debate teams, choral groups and bands.

What are the favorite sports of American young people? According to the survey "The Mood of American Youth," they prefer football, basketball, baseball, wrestling, tennis, soccer, boxing, hockey, track and golf.

During their leisure time, students spend much time watching television. They also listen to music on the radio and tape players. The average American teenager listens to music on the radio about three hours every day. Without a doubt, rock-and-roll music is the favorite of teenagers in the United States.

America's young people are mostly hardworking. Many have after-school jobs. One poll indicated that nine out of 10 teenagers polled said they either had a job or would like one.

Child labor laws set restrictions on the types of work that youths under 16 years old can do. Many youths work part-time on weekends or after school at fast-food restaurants, babysit for neighbors, hold delivery jobs or work in stores.

Many youths are involved in community service organizations. Some are active in church and religious-group activities. Others belong to youth groups such as Girl Scouts or Boy Scouts. About three million girls aged six to 17 years old belong to Girl Scouts, for example. They learn about citizenship, crafts, arts, camping and other outdoor activities.

Thousands of young people volunteer to help take care of the elderly, the handicapped and hospital patients. Many help clean up the natural environment.

YOUTH'S PROBLEMS

To some observers, teens today may seem spoiled (undisciplined and egocentric) compared to those of earlier times. The reality, however, is different. While poverty has decreased and political turmoil has lessened, young people are still under many types of stress. Peer pressure, changing family conditions, mobility of families and unemployment are just a few reasons why some young people may try to escape reality by turning to alcohol or drugs. However, most young people in the United States do not have problems with drinking, drug abuse, teen pregnancies or juvenile delinquency. Drug use (marijuana and cocaine are the most commonly used drugs) has decreased among young people in the United States within the last 10 years, though alcohol abuse has increased.

According to a 1991 government survey, about 8 million teenagers are weekly users of alcohol, including more than 450,000 who consume an average of 15 drinks a week. And, although all 50 states prohibit the sale of alcohol to anyone under 21, some 6.9 million teenagers, including some as young as 13, reported no problems in obtaining alcohol using false identification cards. Although many teenagers say they never drive after drinking, one-third of the students surveyed admitted they they has accepted rides from friends who had been drinking.

Many young Americans are joining organizations to help teenagers stop drinking and driving. Thousands of teenagers have joined Students Against Driving Drunk (SADD). They sign contracts in which they and their parents pledge not to drive after drinking. In some schools, students have joined anti-drug programs. Young people with drug problems can also call special telephone numbers to ask for help.

Aside from drug abuse, another problem of America's youths is pregnancy among young women. One million teenagers become pregnant each year. Why are the statistics so high? The post-World War II baby boom resulted in a 43 percent increase in the number of teenagers in the 1960s and 1970s. The numbers of sexually active teens also increased. And some commentators believe that regulations for obtaining federal welfare assistance unintentionally encourage teenage pregnancies.

Many community programs help cut down on the numbers of teenage pregnancies. Some programs rely on strong counseling against premarital sex and others provide contraceptive counseling. The "Teen Health Project" in New York City has led to a decline of 13.5 percent in the rate of teenage pregnancies since 1976. Why? Their program offers health care, contraceptive counseling, sports programs, job referrals and substance abuse programs.

About one million young people run away from home each year. Most return after a few days or a few weeks, but a few turn to crime and become juvenile delinquents. In 1989, approximately one-third of those

arrested for serious crimes were under 18 years of age. Why are young people committing crimes? Among the causes are poor family relationships (often the children were abused or neglected while growing up), bad neighborhood conditions, peer pressure and sometimes, drug addiction.

Laws vary from state to state regarding juvenile delinquents. Once arrested, a juvenile must appear in a juvenile court. Juvenile courts often give lighter punishments to young people than to adults who commit the same crime. Juvenile courts hope to reform or rehabilitate the juvenile delinquent.

New programs to help troubled youths are created every year. For example, the city of New York and the Rheedlen Foundation provide an after-school program at a junior high school to help keep teens from becoming juvenile delinquents. Young people can go after school and talk with peer counselors (people their own age), receive academic tutoring or take part in athletic and social activities. One New York community's library offers weekday evening workshops in dance, art, music and theater. They also sponsor social events, such as theater productions, in which young people can participate. Another group, the "Youth Rescue Fund" has a celebrity peer council of 15 teenage actors and actresses who volunteer their time to increase teen crisis awareness. As one young television actress said: "Teenagers are an important resource in improving the quality of life for all people."

THE FUTURE

Most American youths look forward to their future with hope and optimism. According to the survey "The Mood of American Youth," teenagers "place a high priority on education and careers. While filled with high hopes about the years before them, today's students are not laboring under any misconceptions about what they must do to realize their aspirations. They admit that hard work lies ahead and claim they are willing to make the sacrifices needed to reach their goals."

Many young people are headed toward four-year colleges and universities. More than half of all students in the United States plan to earn a college degree. Many others look forward to getting a job after high school or attending a two-year junior college. Others plan on getting married. The median age for males getting married for the first time is 26.2 years old, for females, 23.8 years old.

Other young people intend to join the armed forces or volunteer organizations. For some, travel is the next step in gaining experience beyond high school.

During the early 1980s, career success was the prime goal of most young people. But, by the end of the decade, attitudes were changing and young people were becoming more idealistic. A 1989 survey of high school leaders showed that "making a contribution to society" was more than twice as important to young people as "making a lot of money."

American youth are concerned about problems confronting both their own communities and the world around them. In a 1990 poll, American young people said that the most important issues they had to face were: drug abuse, AIDS, and environmental problems.

Young people in the United States are also concerned with global issues such as nuclear war and world hunger. They care for other people around the world, as is evident by such efforts as "The Children for Children Project," in the course of which a group of New York City children worked to raise $250,000 to help the starving children of Ethiopia in 1985. Then they challenged other students in the United States to join in the fund-raising activities. Also in 1985, a benefit called "Live Aid" staged two rock music concerts simultaneously in England and the United States and raised about $50 million to bring relief to starving people in Africa.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Bremner, Robert H. et al., eds. Children and Youth in America: A Documentary History. Vol 1:1600-1865. Vol. 2:1866-1932.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971

George, Patricia L., ed. The Mood of American Youth.

Reston, VA: National Association of Secondary School Principals, 1984.

Gordon, Michael, ed.

The American Family in Social-Historical

Perspectives. 3rd ed.

New York: St. Martin's Press, 1983. Osterman, Paul.

Getting Started: The Youth Labor Market. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1980.

Youth Problems: Timely Reports to Keep Journalists, Scholars and the Public Abreast of Developing Issues, Events and Trends. Washington: Congressional Quarterly, 1982.

Date: 2015-02-28; view: 4507

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| LABOR IN AMERICA | | | LITERATU RE: 1600 TO 1914 |