CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

MEDICINE AND HEALTH CARE

By Anne Cusack (Educational Writer)

In the final decades of the 20th century, Americans increasingly view good health as something to which they have a right. They believe they have a right to good health because widespread advances in medical research have made it possible to treat many previously "unbeatable" diseases, and because the Constitutional responsibility of the American government to "promote the general

Welfare" is far more broadly interpreted today than it has been in the past. These rising expectations regarding health care in the United States are a result of vastly increased medical knowledge; and the belief that in an affluent and democratic society all people should have access to well-trained physicians, fully equipped hospitals and highly sophisticated procedures for the treatment of disease. While remarkable progress in the field of medicine has satisfied many of these expectations, each new discovery or procedure brings with it new challenges to be overcome and new questions to be answered. One example is the treatment of heart disease.

Treatment of heart disease is one of modern medicine's triumphs. Today surgeons routinely perform heart surgery that would have been extraordinary, or even unthinkable, just a few years ago. Even heart transplants, though by no means routine, are becoming more common. In 1987, 1,441 were performed in the United States. Transplants, however, pose serious difficulties: a donor heart must become available, blood and tissue must match, and the patient's immune system must be suppressed with medication to ensure that the body does not reject the new heart.

THE ARTIFICIAL HEART

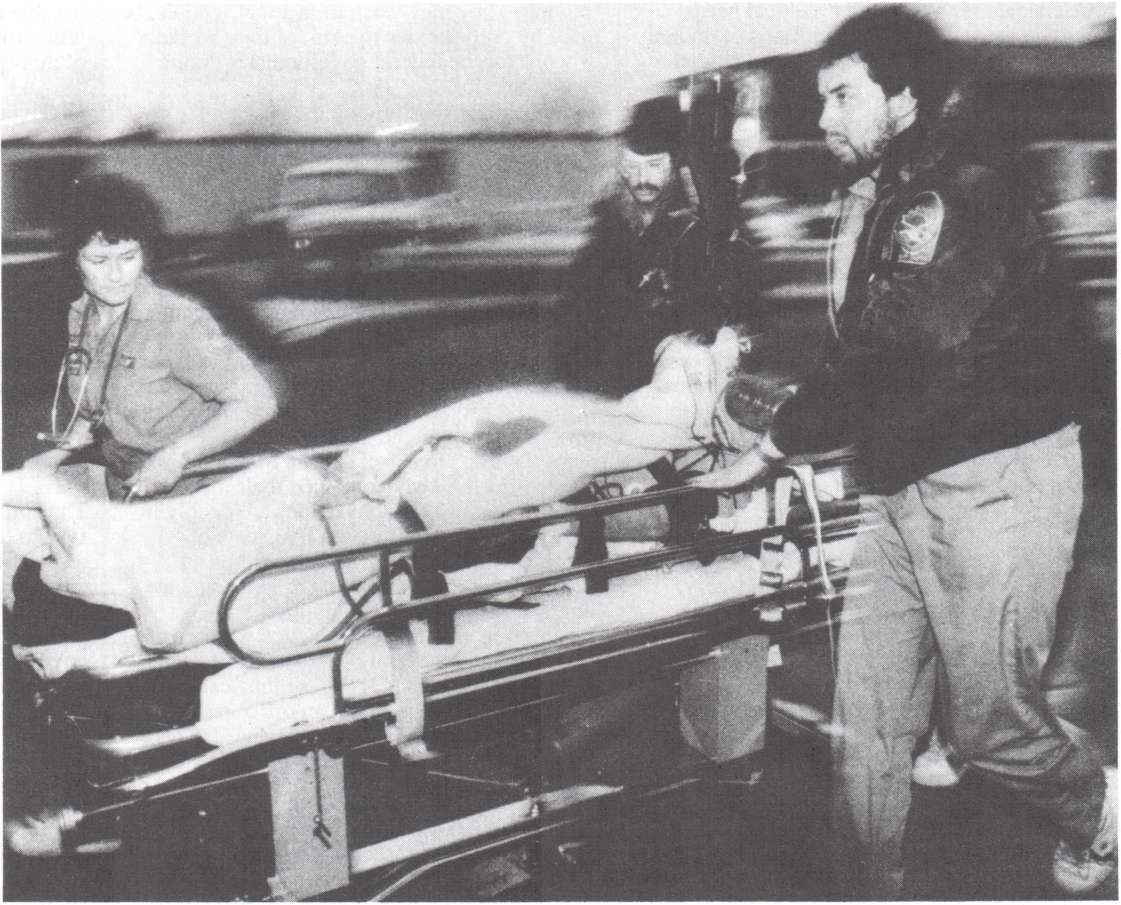

In 1982, American physician William C. DeVries undertook a major step beyond transplants when he implanted an artificial heart known as the Jarvik-7 into the chest of a retired

the Humana Corporation, which owns a chain of private hospitals, Dr. DeVries implanted artificial hearts into two patients, which successfully kept blood pumping steadily through their bodies. However, both patients remained ill, suffered strokes, or brain seizures, and other complications. One of these patients, however, survived for nearly two years before dying in mid-1986.

The artificial heart is a great achievement for modern medicine, but it also poses important questions that are at the center of the debate over the course of medical care in the United States. For example, does the artificial heart offer enough benefits to patients to justify the suffering caused by such an operation? What is the quality of life for an individual who, for the time being, must remain attached to the bulky air compressor which powers the heart? Who should be chosen to receive artificial hearts? What other medical needs might be neglected if many millions of dollars are spent on providing people with artificial hearts?

ACHIEVEMENTS AND LIMITS

The development of the artificial heart represents the kind of dramatic medical advance that Americans have come to expect in recent decades. As medical knowledge has advanced, so has average life expectancy, from 69 years in the 1950s and '60s to 75 years today. Physicians now can treat heart disease and cancer with a variety of drugs or surgical techniques. Individuals whose kidneys have failed can live for years with regular dialysis, or cleansing of their blood, to remove waste products. Drugs are used to control high blood pressure—a risk factor in both strokes and heart attacks. Cardiac pacemakers, or heart regulators, keep many people from dying of abnormalities in the heart rhythm. Surgery, drugs and radiation treatments keep cancer patients alive longer. Childhood leukemia and Hodgkins' disease no longer carry with them an automatic sentence of death. Surgeons can replace damaged joints with artificial ones, and eye doctors use lasers and other advanced techniques to preserve or restore sight. Advances in microsurgery have even made it possible to reattach limbs which have been detached in accidents, and burn victims benefit from the development of new skin grafting techniques. Among the hundreds of newly developed drugs are tranquilizers, or calming drugs, which have made it possible to release many patients from mental hospitals.

Physicians, however, are not miracle workers, and the public's expectations of medical progress sometimes outstrip reality. About 65 percent of Americans who died in 1988 suffered from cancer, heart disease or other problems of the circulatory system. Modern medicine can treat—but usually not cure—such conditions: There are no inoculations against cancer or heart disease. Since physicians often cannot predict who will benefit from a treatment, they generally recommend treating every patient who has even a slight chance of benefiting. On the other hand, many medical tests and procedures involve risk, so the value of medical treatment must be weighed against the possibility that the procedure itself may cause disease or injury.

THE PHYSICIAN

Self-employed private physicians who charge a fee for each patient visit are the foundation of medical practice in the United States. Most physicians have a contractual relationship with one or more hospitals in the community. They send their patients to this hospital, which usually charges patients according to the number of days they stay and the facilities— operating room, tests, medicines—that they use. Some hospitals belong to a city, a state or, in the case of veteran's hospitals, a federal government agency. Others are operated by religious orders or other non-profit groups. Still others operate for profit.

Some medical doctors are on salary. Salaried physicians may work as hospital staff members, or residents, who often are still in training. They may teach in medical schools, be hired by corporations to care for their workers or work for the federal government's Public Health Service.

Physicians are among the best paid professionals in the United States. In the 1980s, it is not uncommon for medical doctors to earn incomes of more than $100,000 a year. Specialists, particularly surgeons, might earn several times that amount. Physicians list many reasons why they deserve to be so well rewarded for their work. One reason is the long and expensive preparation required to become a physician in the United States. Most would- be physicians first attend college for four years, which can cost nearly $20,000 annually at one of the best private institutions. Prospective physicians then attend medical school for four years. Tuition alone can exceed $10,000 a year. By the time they have obtained their medical degrees, many young physicians are deeply in debt. They still face three to five years of residency in a hospital, the first year as an intern, an apprentice physician. The hours are long and the pay is relatively low.

Setting up a medical practice is expensive, too. Sometimes several physicians will decide to establish a group practice, so they can share the expense of maintaining an office and buying equipment. These physicians also take care of each other's patients in emergencies.

Physicians work long hours and must accept a great deal of responsibility. Many medical procedures, even quite routine ones, involve risk. It is understandable that physicians want to be well rewarded for making decisions which can mean the difference between life and death.

MEDICAL COSTS

Physicians' fees are only one reason for rising health costs in the United States. Medical research has produced many tests to diagnose, or discover, patients' illnesses. Physicians usually feel obliged to order enough tests to rule out all likely causes of a patient's symptoms. A routine laboratory bill for blood tests can easily be more than $100.

Sophisticated new machines have been developed to enable physicians to scan body organs—even the brain—with a clarity never before possible. One technique involves the use of ultrasound—sound waves beyond the frequencies that human beings can hear—to produce images. Others use computers to capture and analyze images produced by X-rays or magnetic fields.

These machines often make unnecessary older diagnostic tests which are painful and sometimes dangerous. But the machines are extremely expensive: The price of a single machine can exceed one million dollars.

New technologies also mean new personnel. Physicians, nurses and orderlies i no longer staff a hospital alone. Hospitals n require a bewildering number of technical specialists to administer new tests and open advanced medical equipment.

Physicians and hospitals also must buy malpractice insurance to protect themselves should they be sued for negligence by patients who feel they have been mistreated or have received inadequate care. The rates that physicians were charged for this insurance i very steeply in the 1970s and '80s as patients became more medically knowledgeable, and juries sometimes awarded very large amour of money to injured patients.

As a result, hospital costs and physicians' fees rose steadily through the 1960s and '70s. By 1986, the average cost a stay in the hospital had climbed to more than $500 a day. Government agencies became convinced that it was necessary to limit rising medical costs. One approach i: require hospitals to prove that a need exist for new buildings and services. Hospitals; have faced pressure to run their operations more efficiently, and to decrease the duration of hospital stays for patients receiving routine treatment or minor surgery.

PAYING THE BILLS

The United States today has evolved a mixed system of private and government responsibility for health care. While private citizens and health insurance companies spent about 230 thousand million dollars on health care in 1986, federal, state and local governments spent 179 thousand million dollars for medical services of all kinds. Public funds financed much of the research on the artificial heart, but it was a private corporation Humana, which paid for artificial heart surgery and patient care. This interchange between public and private sectors is typical of how United States provides many kinds of health and medical services.

How do most Americans pay their medical bills? For the vast majority, the answer is medical insurance. About five out of even six workers, along with their families, are covered by group health insurance plans, paid for jointly by the employer and employee î the employee alone. Under the most common type of health plan, the individual pays a monthly premium, or fee. Typically, employees who wish more extensive medical coverage will choose a plan requiring higher premiums.

In return, the insurance company covers most major medical costs, except for a minimum amount, called the "deductible," which the employee pays each year before insurance coverage begins. Benefits then cover a certain percentage, often 80 percent, of the patient's bills in excess of the deductible. S policies provide that after the employee's b have reached a certain amount, the insurer covers 100 percent of all additional costs. Depending on the plan, deductible amounts

most health insurance policies range from $50 to $300. Insurance plans vary considerably, with some offering coverage for dental costs and others providing for mental health counseling and therapy.

Another type of health care plan available to many workers is a Health Maintenance Organization (HMO). An HMO is staffed by a group of physicians who agree to provide all of an individual's medical care for a set fee paid in advance. HMOs emphasize preventive health care, since the organization loses money rather than gaining fees when it is necessary to prescribe treatment or place someone in the hospital. For this reason, medical experts generally credit HMOs with helping to hold down overall medical costs. In 1987, about 660 HMOs served about 29 million people.

MEDICAID AND MEDICARE

Although most families have some form of private health insurance, some citizens cannot afford such insurance. These people receive medical coverage through two major social programs enacted in 1965.

Medicaid is a joint federal-state program which funds medical care for the poor people. The requirements for receiving Medicaid, and the scope of the medical care available, vary widely from state to state. Medicaid has proved more costly than expected, and has been exploited for unjustified gain by some physicians. As a result, the government has decreased Medicaid services by making the requirements for those entitled to participate in the program more strict. Nonetheless, Medicaid has greatly increased the use of health care services by the poor.

Medicare is a federal program financed through the Social Security Administration, which provides a national system of retirement and other benefits. Medicare pays a substantial part of the medical bills of Americans who are over 65 years of age or are disabled. Medicare is not a poverty program, but is rather a form of federally administered and supported health insurance. One part of Medicare covers a major portion of hospital bills for the elderly and is financed by a portion of the Social Security tax. Another part is financed by premiums paid by Medicare recipients, as well as from direct federal funds. Everyone who collects Social Security is covered by Medicare.

As is the case with the rest of the health care system in the United States, Medicare has felt the pressure of rising costs. In response, the government has taken two steps. First, Medicare has raised the amount of the deductible that patients must pay before insurance benefits begin. Second, it has changed its method of paying hospitals. Instead of paying hospitals through a vague formula called "reasonable charges," Medicare now pays according to the patient's diagnosis. This provides an incentive for the hospital to keep costs down. If, for example, the hospital can treat a patient who needs gall bladder surgery for less than Medicare pays to treat such an illness, the hospital makes a profit. If the patient's treatment costs more than Medicare pays, the hospital loses money.

In addition to controlling costs, the United States confronts the problem of those who cannot afford private health insurance and yet are not eligible for either Medicaid or

Medicare. One estimate is that more than 30 million people or 1 in 7 Americans have no health insurance during at least part of the year. These may be individuals who are unemployed for a time, families close to the poverty line or those living in remote rural areas. Such individuals can go to public hospitals, where they can always receive treatment in an emergency, but they often fail to obtain routine medical care that could prevent later chronic or serious illness.

ETHICAL ISSUES

The very successes of modern medicine have produced issues and dilemmas unknown in previous periods. The ability to treat newborn infants with severe deformities is one example. Should expensive operations be performed to save the lives of babies who will be seriously retarded or disabled all of their lives? Some parents want every possible effort made to save such babies, in the hope that treatment to improve their child's condition may be developed in the future. Others, less optimistic, think that an early death is better than a life of pain and suffering. In either case, who should make such life-or-death decisions: the parents, the physician, the hospital administrators, the community (through passage of laws)?

The availability of amniocentesis and legal abortion also raises complicated ethical questions. Physicians can now withdraw a small amount of the amniotic fluid that surrounds a fetus in the womb. They can thus obtain fetal cells and study them for possible abnormalities. They can tell, for example, whether the fetus has Down's Syndrome, a defect that causes mental retardation and, often, other physical disabilities. Since amniocentesis carries a slight risk of harming the fetus, it is usually performed only on older mothers who are at greater risk for giving birth to infants suffering from birth defects. Many types of birth defects, however, cannot be discovered through amniocentesis.

Parents who learn of severe abnormalities can choose to abort the fetus prior to the 24th week of pregnancy. Abortion, however, is an intensely controversial subject in the United States, as it is in many other countries. Although abortion is legal in the United States, many feel that it should be legal only when the mother's life is in danger. Others believe that abortion should never be undertaken under any conditions.

Occasionally, a very small living infant is born prematurely. Such infants seldom survive, and the risk of their suffering permanent handicaps is great. Many hospitals have established special intensive care units which can now save many such premature babies. But should all premature infants be treated in this manner, especially if they are below a certain weight and therefore likely to suffer severe disabilities?

At the other end of the spectrum, the situation of unconscious patients also triggers intense debate. Physicians can use respirators—machines that breathe for patients—and other medical equipment to keep patients alive indefinitely, even though the patients will not regain consciousness. When is it proper to turn off these machines and let the patient die?

Most physicians now recognize that there is a point at which further treatment merely prolongs the agony of death, and with the family's consent, they may decide not to resuscitate (restart the stopped heart) an old person dying of cancer. Young victims of auto accidents who are unconscious pose a different set of issues. Often, the decision to maintain an unconscious, critically ill patient may turn on whether or not the person is "brain-dead"— with no measurable electrical activity in the brain. Physicians today recognize that these patients are, in fact, dead, and their life support systems can be removed. Such patients also become valuable sources of organs for transplants for other patients.

HEALTH CARE CHALLENGES

Although Americans, on the average, are healthier and live longer today than ever before, a number of challenges still confront the medical care system in the United States. While advanced technology can provide artificial hearts or transplanted kidneys to a few at high cost, others still suffer from diseases, such as tuberculosis, that medicine already has "conquered."

Older Americans are one of the fastest growing segments of the population. About five percent of the elderly population live in nursing homes. Many suffer from Alzheimer's disease, an increasingly common ailment that affects the brain, leaving its victims mentally confused and hard to care for. Other patients, who might have died in previous years from strokes and other ills, live on; but they suffer from speech and memory defects, paralysis and other disabilities. As Americans have grown more aware of the specific health needs of the elderly, the field of gerontology, the study of the aging process, has attracted increasing numbers of physicians. Medical research has focused on this health issue as well, notably with the establishment of the federal government's National Institute on Aging.

The nation's infant mortality rate is also a concern. The number of infants per thousand live births who died before their first birthday remains higher for the United States than for several other industrialized nations. This rate is also higher for blacks and other minorities than for white Americans. Health authorities agree that better nutrition and prenatal (before birth) health care could substantially lower the infant mortality rate among these minority groups.

Delivering better health care to poor and disadvantaged groups in the United States is only one way of improving the nation's overall health. Research in recent years has made it clear that much disease is the result of the way people choose to live. Money spent to persuade people to lose weight, exercise regularly, eat more healthful foods and stop smoking can often provide greater benefits for more people than the most advanced medical technologies. For example, studies have linked a significant drop in the rate of lung cancer to a nationwide decline in cigarette smoking.

Another severe challenge to the health care system is Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, or AIDS.

This worldwide disease, first reported in the United States in 1981, is caused by a virus spread by sexual contact, needle sharing (such as in illegal drug use) or exchange of blood (such as in transfusions). Since 1981, more than 83,000 Americans have died of AIDS. Scientists and pharmaceutical companies are

working on vaccines to prevent this disease and medicines to treat it. As of 1991, several drugs had been developed to treat some of the symptoms of AIDS, but not to cure or prevent the disease.

In addition to the grief and pain caused by this disease, it has strained the system because many AIDS patients do not have adequate health insurance. Some are cared for by friends and relatives or at clinics run by churches and other groups. Others are treated in hospitals under the Medicaid program.

PATTERNS OF CHANGE

The health care system in the United States today is in a period of rapid change on many different fronts. One example is the distribution of medical services. By the mid-1980s, the United States, in a reversal of a long-standing pattern, no longer faced a shortage of physicians. There was, in fact, a developing surplus of medical doctors. But physicians often prefer to practice in urban areas or comfortable suburbs. As a result, many inner city areas and rural communities still lack sufficient physicians and adequate medical facilities.

As the number of medical specialties has grown in recent years, patients sometimes have found it frustrating to deal with a number of different physicians for differing ailments, rather than with the traditional family physician. Medical schools have responded by creating a new specialty—family medicine. Such family physicians can diagnose and treat many kinds of illnesses, though they also send patients to specialists when necessary. Not every medical problem requires a highly trained specialist, or even a physician. In some communities, physicians' assistants, working with medical doctors, perform some routine medical procedures. Nurse mid wives manage normal pregnancies and deliveries, calling upon obstetricians only if problems develop.

The Humana Corporation's highly publicized artificial heart program highlights another change in American medical practice. Profit-making corporations are playing an increasingly large role in providing medical care, and chains of private, "for-profit" hospitals are growing. Private companies also compete for contracts to run public hospitals for a fee, promising more efficient and cost- conscious management.

Can profit-making corporations deliver more economical and higher quality medicine? Or do they simply draw patients with sufficient funds or health insurance away from non-profit and public hospitals, leaving these institutions to cope with the poorest and sickest patients?

Liberal social critics deplore the lack of government planning and central oversight inherent in a free market approach to health care. Conservative critics, on the other hand, feel that government-funded health insurance and medical programs are inefficient and more expensive than private medical care in the long run. Critics on both sides often agree, however, the medical profession has been given too much freedom in determining the cost of medical care.

While some groups might benefit from funds spent to improve medical care further, many people feel that differences in the way people live account for much of the health gap between rich and middle class and the poor. Is it possible to spend too much money saving a single life? Would spending less money on advanced medical treatments increase the amounts available for better nutrition, pollution controls, safety devices, campaigns to increase exercise and cut back smoking, and other preventive measures? Should people be held responsible for habits and behaviors which make them sick?

Physicians, politicians, medical experts and ordinary citizens were debating these questions in the early 1990s. The answers are by no means clear-cut, but involve a number of trade-offs and compromises between equally desirable goals. In a nation in which more than 11 percent of the Gross National Product (the value of all goods and services) is spent on medical services of all kinds, Americans are in agreement on one central point: Quality, affordable health care must be available to everyone.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Aaron, Henry J.

Painful Prescription: Rationing Hospital Care. Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 1984.

Gorovitz, Samuel. Doctor's Dilemmas: Moral Conflict and Medical Care. New-York: Macmillan, 1982.

Starr, Paul.

The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic Books, 1982.

Thomas, Lewis. The Youngest Science: Notes of a Medicine-Watcher. New York: Viking, 1983.

U.S. Office of Technology Assessment. Medical Technology and Costs of the Medical Program. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1984.

Date: 2015-02-28; view: 5212

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| THE PUBLIC WELFARE SYSTEM IN AMERICA | | | RELIGION IN AMERICA |