CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

HISTORY: 1865 TO 1929

By Jonathan Rose (Drew University)

Though the victory of the North in the American Civil War assured the integrity of the United States as an indivisible nation, much was destroyed in the course of the conflict, and the secondary goal of the war, the abolition of the system of slavery, was only imperfectly achieved.

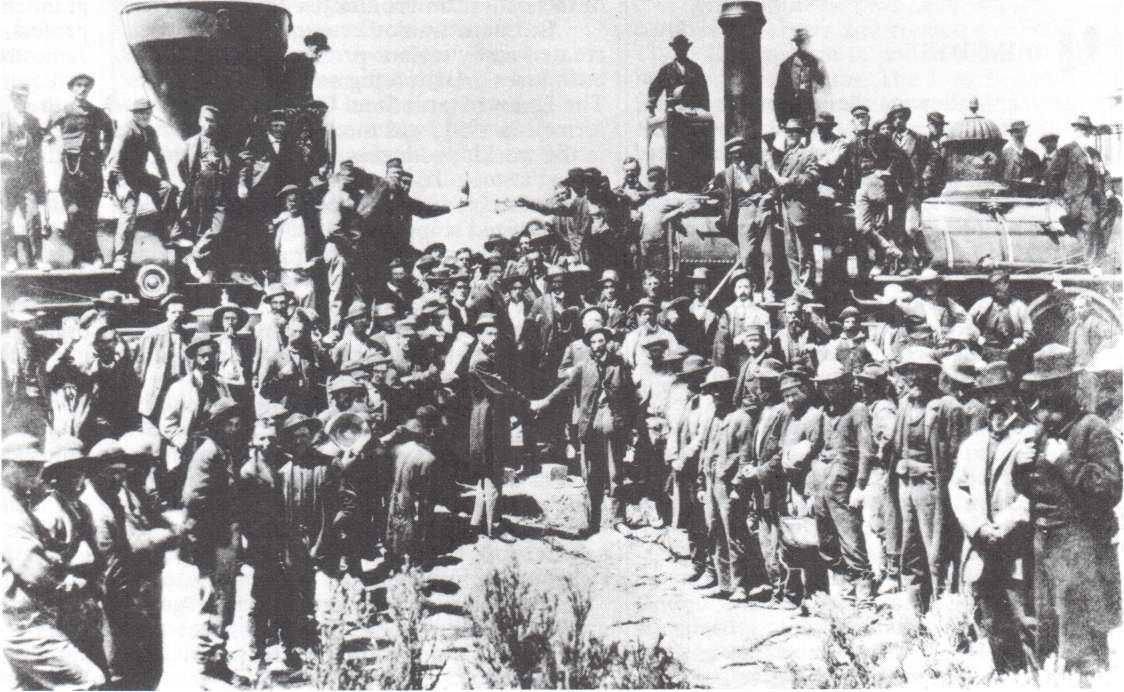

At Promontory Point, Utah, workers celebrate completion of th

e first transcontinental railroad in 1869.

The railroad was a key element in the transformation of the

United States from a predominately agricultural to an industrial nation.

Union Pacific Railroad

RECONSTRUCTION

The defeat of the Confederacy (Southern states) left what had been the country's most fertile agricultural area economically destroyed and its rich culture devastated. At the same time, the legal abolition of slavery did not ensure equality in fact for former slaves. Immediately after the Civil War, legislatures in the Southern states7-fearful of the way in which former slaves might exercise the right to vote and also eager to salvage what they could of their former way of life, attempted to block blacks from voting.

They did this by enacting "black codes" to restrict the freedom of former slaves. Although "radical" Republicans in Congress tried to protect black civil rights and to bring blacks into the mainstream of American life, their efforts were opposed by

President Andrew Johnson, a Southerner who had remained loyal to the Union during the Civil War. He served as the Republican vice president, and was elevated to the presidency on the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

In March 1868, the House of Representatives responded to Johnson's opposition to radical solutions by attempting to remove him from office. The charges against him were groundless, and a motion to convict the president was defeated in the Senate. Johnson had, in the opinion of many people, been too lenient toward former Confederates, but his acquittal was an important victory for a central principle of American government. The principle is the separation of powers between the legislative, executive and judicial branches of government. Johnson's acquittal helped preserve the delicate balance of power between the president and Congress.

Congress nevertheless was able to press forward with its program of "Reconstruction," or reform, of the Southern states, occupied after the war by the army of the North. By 1870, Southern states were governed by groups of blacks, cooperative whites and transplanted Northerners (called "carpetbaggers"). Many Southern blacks were elected to state legislatures and to the Congress. Although some corruption existed in these "reconstructed" state governments, they did much to improve education, develop social services and protect civil rights.

Reconstruction was bitterly resented by most Southern whites, some of whom formed the Ku Klux Klan, a violent secret

society that hoped to protect white interests and advantages by terrorizing blacks and preventing them from making social advances. By 1872, the federal government had suppressed the Klan, but white Democrats continued to use violence and fear to regain control of their state governments. Reconstruction came to an end in 1877, when new constitutions had been ratified in all Southern states and all federal troops were withdrawn from the South.

Despite Constitutional guarantees, Southern blacks were now "second-class citizens"—that is, they were subordinated to whites, though they still had limited civil rights. In some Southern states, blacks could still vote and hold elective office. There was racial segregation in schools and hospitals, but trains, parks and other public facilities could still generally be used by people of both races.

Toward the end of the century, this system of segregation and oppression of blacks grew far more rigid. In the 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution permitted separate facilities and services for the two races, so long as these facilities and services were equal. Southern state legislatures promptly set aside separate— but unequal—facilities for blacks. Laws enforced strict segregation in public transportation, theaters, sports, and even elevators and cemeteries. Most blacks and many poor whites lost the right to vote because of their inability to pay the poll taxes (which had been enacted to exclude them from political participation) and their failure to pass literacy tests. Blacks accused of minor crimes were sentenced to hard labor, and mob violence was sometimes perpetrated against them. Most Southern blacks, as a result of poverty and ignorance, continued to work as tenant farmers. Although blacks were legally free, they still lived and were treated very much like slaves.

MOVIIMG WEST

In the years following the end of the Civil War in 1865, Americans settled the western half of the United States. Miners searching for gold and silver went to the Rocky Mountain region. Farmers, including many German and Scandinavian immigrants, settled in Minnesota and the Dakptas. - Enormous herds of cattle grazed on tfie plains of Texas and other western states, managed by hired horsemen (cowboys) who became the most celebrated and romanticized figures in American culture. Most of these horsemen were former Southern soldiers or former slaves, both of whom headed west after the defeat of the South. The cowboy was America's hero: He worked long hours on the open range for low wages. He was not nearly as violent as movies later represented him to be.

Settlers and the United States Army fought frequent battles with Indians, upon whose lands the stream of white settlers was encroaching, but here, too, the bloodshed has been exaggerated. A total of perhaps 7,000 whites and 5,000 Indians were killed in the course of the 19th century. Many more Indians died of hunger and disease caused by the westward movement of settlers. White men forced the Indians from their land and nearly destroyed all of the buffalo, the main source of food and hides for the tribes of the Great Plains.

INDUSTRIAL GROWTH

During this period, the United States was becoming the world's leading industrial power, and great fortunes were made by shrewd businessmen. The first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869. Between 1860 and 1900, total rail mileage increased from 31,000 to almost 200,000 (5,000 to 322,000 kilometers)— more than in all of Europe. To encourage this expansion, the federal government granted loans and free land to western railroads.

The petroleum industry prospered, dominated by John D. Rockefeller's giant Standard Oil Company. Andrew Carnegie, who came to America as a poor Scottish immigrant, built a vast empire of steel mills and iron mines—which he sold in 1901 for nearly 500 thousand million dollars. Textile mills multiplied in the South, and meatpacking plants sprang up in and around Chicago. An electrical industry was created by a series of inventions—the telephone, the phonograph, the light bulb, motion pictures, the alternating-current motor and transformer. In Chicago, architect Louis Sullivan used steelframe construction to develop a peculiarly

American contribution to the cities of the world—the skyscraper.

Nineteenth-century Americans pointed with pride at these accomplishments—and with good reason. The United States has always been hospitable to inventors, experimenters and entrepreneurs. The freedom to develop new enterprises largely accounts for the vitality of the American economy.

But unrestrained economic growth created many serious problems. Some businesses grew too big and too powerful. The United States Steel Corporation, formed in 1901, was the largest corporation in the world, producing 60 percent of the nation's steel. To limit competition, railroads agreed to mergers and standardized shipping rates. "Trusts"— huge combinations of corporations—tried to establish monopoly control over some industries, especially oil.

These giant enterprises could produce goods efficiently and sell them cheaply, but they could also set prices and destroy smaller competitors. Farmers in particular complained that railroads charged high rates for hauling produce. Most Americans, then as now, admired business success and believed in free enterprise; but they also believed that the power of monopolistic corporations had to be limited to protect the rights of the individual.

One answer to this problem was government regulation. The Interstate Commerce Commission was created in 1887 to control railroad rates. In 1890, the Sherman Antitrust Act banned trusts, mergers and business agreements "in restraint of trade." At first, neither of these measures was very effective, but they established the principle that the federal government could regulate industry for the common good.

LABOR, IMMIGRANTS, FARMERS

Industrialization brought with it the rise of organized labor. The American Federation of Labor, founded in 1881, was a coalition of trade unions for skilled workers. It agitated not for socialism, but for better wages and shorter working hours. Around 1900, the average unskilled laborer worked 52 hours a week for a wage of nine dollars. In the 1890s, discontent over low wages and unhealthful working conditions triggered a wave of industrial work stoppages, some of them violent. Several workers and company guards were killed during an 1892 strike at the Carnegie Steel plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania. In 1894, Army troops were sent to Chicago to end a strike of railroad workers.

Many of the workers in these new industries were immigrants. Between 1865 and 1910, 25 million people came to the United States, many of them settling in large enclaves in major American cities. At the insistence of laborers who feared Asian immigrants because of their willingness to accept low wages for unskilled work, federal legislation barred the entry of Chinese in 1882. The Japanese were largely excluded in 1907, but most other arrivals were free to enter the United States. Immigrants often encountered prejudice from native-born Americans—who, of course, were themselves descended from immigrants. Still, America offered the immigrants more religious liberty, more political freedom and greater economic opportunities than they could find in their native lands. The first-generation immigrant usually had to struggle with poverty, but his children and grandchildren could achieve affluence and professional success. Since the founding of Jamestown, the first permanent European settlement in North America, in 1607, the United States has accepted two-thirds of al the world's immigrants—a total of 50 million people.

For American farmers, the late 19th century was a difficult period. Food prices were falling, and the farmer had to bear the cost of high railroad shipping rates, expensive mortgages, high taxes and tariffs on consumer goods. Several national organizations were formed to defend the interests of small farmers—the Grange in 1867, the National Farmers' Alliance in 1877 and the Populist Party in the 1890s. The Populists demanded nationalization of the railroads, a progressive income tax and monetary reform. In 1896, they supported the Democratic presidential candidate, William Jennings Bryan of Nebraska. A great orator, Bryan conducted an active national campaign, denouncing the trusts, the banks and the railroads. Bryan won the votes of the agricultural states of the South and the West, but he lost the election to William McKinley, a conservative Republican.

OVERSEAS EXPANSION

With the exception of the purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867, American territorial expansion had come to a virtual standstill in 1848. However, in about 1890, as many European nations were expanding their colonial empires, a new spirit entered American foreign policy, largely following northern European patterns. Politicians, newspaper editors and Protestant missionaries proclaimed that the "Anglo- Saxon race" had a duty to bring the benefits of Western civilization to the peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America

At the height of this period (1895), a revolt against Spanish colonialism erupted in Cuba. The Spanish army herded Cuban civilians into camps, where as many as 200,000 people died of disease and hunger. In the United States, newspaper owners such as William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer published lurid accounts of Spanish atrocities and stirred up popular sentiment for America to liberate the island.

The United States had by now built a modern navy, and in January 1898 the battleship Maine was sent on a visit to Havana, Cuba. On February 15, a mysterious explosion sank the Maine in Havana harbor. It is not clear who or what caused the disaster, but most Americans were convinced at the time that Spain was responsible. The United States demanded that Spain withdraw from Cuba and started mobilizing volunteer troops. Spain responded by declaring war on the United States.

American troops landed in Cuba, and the United States Navy destroyed two Spanish fleets—one at Manila Bay in the Philippines, (a Spanish possession at the time), the other at Santiago in Cuba. In July, the Spanish government asked for peace terms. The United States acquired much of Spain's empire—Cuba, the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Guam. In an unrelated action, the United States also annexed the Hawaiian islands.

In comparison to the empire building of the European powers, America's acquisitive period was limited in scope and of short duration. After the Spanish- American War, Americans justified their actions to themselves on the grounds that they were preparing underdeveloped nations for democracy. But could Americans be imperialists? After all, they had once been a colonial people and had rebelled against foreign rule. The principle of national self-determination was written into the Declaration of Independence. In the Philippines, insurgents who had fought against Spanish colonialism were soon fighting American occupation troops. Many intellectuals, such as the philosopher William James and Harvard University president Charles Eliot, denounced these actions as a betrayal of American values.

Despite the criticisms of the anti- imperialists, most Americans believed that the Spanish conflict had been appropriate and they were eager to assert American power. President Theodore Roosevelt proposed to build a canal in Central America, and in 1903 he offered to buy a strip of land in what is now Panama from the Colombian government. When Colombia refused Roosevelt's offer, a rebellion broke out in the area designated as the canal site. Roosevelt supported the revolt and quickly recognized the independence from Colombia of Panama, which sold the canal zone to the United States a few days later. In 1914, the Panama Canal was opened to traffic.

American troops left Cuba in 1902, but the new republic was required to grant naval bases to the United States. Also, until 1934, Cuba was barred from making treaties that might bring the island into the orbit of another foreign power. The Philippines were granted limited self- government in 1907 and complete independence in 1946. In 1953, Puerto Rico became a self-governing commonwealth within the United States, and in 1959 Hawaii was admitted as the 50th state of the Union.

Date: 2015-02-28; view: 2464

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| HISTORY: LEIF ERICSON TO 1865 | | | PROGRESSIVE MOVEMENT |