CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

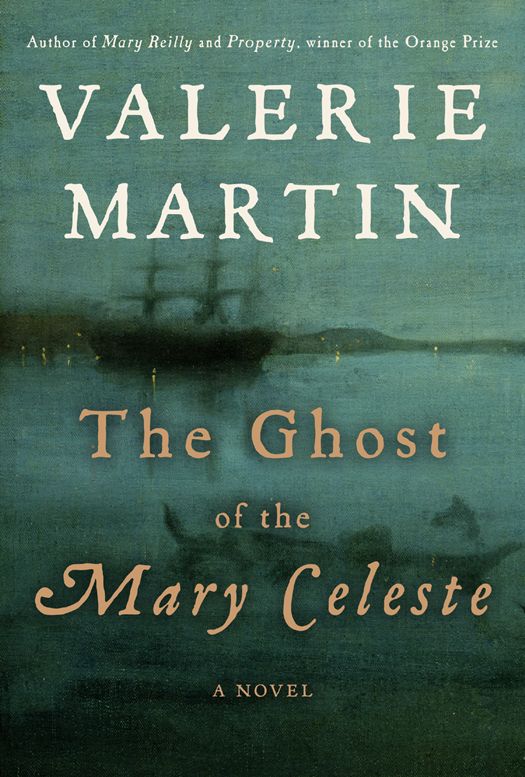

Off the Coast of Cape Fear, 1859

Valerie Martin

The Ghost of the Mary Celeste

Valerie Martin

The Ghost of the Mary Celeste

Dedication

For Adrienne Martin,

who knows how we hope

Epigraph

Why does the sea moan evermore?

Shut out from heaven it makes its moan.

It frets against the boundary shore;

All earth’s full rivers cannot fill

The sea, that drinking thirsteth still.

CHRISTINA ROSSETTI

The unknown and the marvelous press upon us from all sides. They loom above us and around us in undefined and fluctuating shapes, some dark, some shimmering, but all warning us of the limitations of what we call matter, and of the need for spirituality if we are to keep in touch with the true inner facts of life.

ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

A DISASTER AT SEA

The Brig Early Dawn

Off the Coast of Cape Fear, 1859

The captain and his wife were asleep in each other’s arms. She, new to the watery world, slept lightly; her husband, seasoned and driven to exhaustion the last two days and nights by the perils of a gale that shipped sea after sea over the bow of his heavily loaded vessel, had plunged into a slumber as profound as the now tranquil ocean beneath him. As his wife turned in her sleep, wrapping her arm loosely about his waist and resting her cheek against the warm flesh of his shoulder, in some half‑conscious chamber of her dreaming brain she heard the ship’s clock strike six bells. The cook would be stirring, the night watch rubbing their eyes and turning their noses toward the forecastle, testing the air for the first scent of their morning coffee.

For four days the captain’s wife had hardly seen the sky, not since the chilly morning when their ship, the Early Dawn , set sail from Nantasket Roads. Wrapped in her woolen cloak, she had stood on the deck peering up at the men clambering in the rigging, confident as boys at play, though a few among them were not young. The towboat turned the prow into the wind and the mate called out, “Stand by for a starboard tack.” A sailor released the towline, and as the tug pulled away, the ship creaked, heeling over lightly, and the captain’s wife steadied herself by bending her knees. Then, with a thrill she had not anticipated, she watched as one by one the enormous sails unfurled, high up, fore and aft. A shout went up among the men, so cheerful it made her smile, and for a moment she almost felt a part of the uproarious bustle. We are under way, she thought – that was what they called setting out. A line from a poem she loved crossed her thoughts, “And I the while, the sole, unbusy thing.” Her smile faded. She had left her little son, Natie, with her mother and now she felt, like a blow, his absence. How had she been persuaded to leave him behind?

In the year since their son’s birth, the captain’s wife had not passed two consecutive months in her husband’s company and she was sick of missing him, of writing letters that might never find him, of following his progress on a map. Her mother had urged her to go. Her father, another captain, retired now, home for the duration, avowed that he would have his grandson riding the pony by the time she returned. Her mother offered reassuring stories of her own first trip as the captain’s wife, long years ago, and of the wonders she had seen on the voyage to Callao and the Chincha Islands. “There’s nothing like the open deck on a warm, calm night at sea,” she said. “The vastness of the heavens, the sense of being truly in God’s hands.” And her father chimed in with the time‑honored chestnut, “There are no atheists at sea.”

The captain’s wife lowered her hood and turned to gaze at her husband, who stood nearby, his legs apart, his face lifted, his eyes roving the stretched canvas, which talked to him about the wind. He was a young man, but he had been at sea since he was scarcely more than a boy and had about him an older man’s gravity. His dark eyes, accustomed to taking in much at a glance, were piercing. He was lean, strong, and steady. His frown could stop a conversation; his laughter lifted the spirits of all who heard him. After his first visit to the rambling house they called Rose Cottage, her father had announced, “Joseph Gibbs is as solid a seaman as I know. He keeps his wits about him.”

And now he kept his wife about him. She studied the sailors, absorbed in their labors, each one different from the others, one skittish, one bullying, another diffident, a shirker, a bawler, a rapscallion, and a fool, yet each at his task harkened to the voice of the Master. Doubtless her mother was right – they were all of them in God’s hands, but should the Almighty turn away for a moment, every soul on this ship would shift his faith to the person of Captain Joseph Gibbs.

“I’m going below,” she said to him, and his eyes lowered and settled upon her. He smiled, nodded, turned to speak to the mate who was striding briskly toward them. Clutching the ladder rails, she backed down into the companionway, where she paused a moment, patting down her hair, before entering the cabin. There was, of course, no one there. For an hour she busied herself with sewing, for another in reading a volume of poems. The ship moved around her, above, beneath, rising and settling, picking up speed. A sensation of nausea, no more than a twinge at first, gradually announced its claim on her attention. She stood up, dropping the book on the couch, anxiously looking about the neat little room. She spied a pot hanging from a hook near the table. As she staggered to it, her stomach turned menacingly, and no sooner had she taken up the vessel than she emptied her breakfast into it. “Oh Lord,” she said, pulling out her handkerchief to wipe the perspiration from her brow. She carried the pot through to the cabin and poured the noxious contents into the bucket, then closed the lid and sat down upon it. The sailors, when so afflicted, had the option of vomiting over the side, but it wouldn’t do for the captain’s wife, who wasn’t allowed anywhere near the main deck on her own. She pressed the handkerchief to her lips. Another eruption threatened. Best not stray far from this place, she counseled herself. She wondered how long it would last.

It lasted three days, but during that time her stomach was the least of her problems. When at last the captain descended to find his wife flat on her back in the bunk, fully clothed, with a wet cloth draped across her forehead, it was to tell her that he didn’t like the look of the western sky. For another hour she slept fitfully and woke to hear the officers talking in the wardroom. Her husband came in to ask if she wouldn’t have a cup of tea, which she declined. The ship was pitching bow to stern and he held on to the bedframe as he bent over to press his cool hand against her cheek. “My poor darling,” he said. “You’re pea‑green. What a way to begin your maiden voyage.” At the word “maiden,” she smiled; it was a joke between them.

“Don’t worry about me,” she said.

There was a shout from the deck, a clatter of boots in the companionway. The captain made for the door. “Here it comes,” he announced as he went out.

It was a squall out of the northwest, which shifted to the southwest and blew a hard gale for eighteen hours. A jib and a topgallant were carried away, as well as a rooster, last seen wings outspread riding backward on a blast of spray. Gradually the wind abated, though the sea was still high, kneading the ship like bread dough between the waves.

The captain’s wife didn’t witness the storm. When it seemed the bunk was determined to dump her on the carpet, she turned on her side, gripping the frame. All she could hear was the wind howling, the timbers creaking, and the men shouting. At last it grew calmer; she lifted her head and glanced about the cabin. Her small collection of books had been scattered widely, as if an impatient reader, pacing the carpet in search of some vital information, had thrown down volume after volume. There was a knock at the door and to her query “Who is it?” the nasal voice of the steward Ah‑Sam replied, “Mrs. Gibbs. I have tea for you.”

She scrambled from the bed, relieved to find, as she sat on the chest next to her empty bookshelf, that her stomach, though decidedly tender, was calm. “Come in,” she said.

Cautiously, his head bowed and his legs wide apart to keep himself steady, Ah‑Sam came in holding a mug between his hands. “This beef tea,” he said. “Good for stomach.” She reached out, taking the cup, but before she had time to speak, the man had backed out the door. “Thank you,” she said, as the latch clicked behind him. The broth was dark, clear, fragrant, revitalizing. She sipped it, swaying lightly as the ship swayed, and planned her next appearance above deck.

But by the time she had washed and changed her clothes, the wind had turned to the east, the heavens crackled with lightning, the rain came on in torrents, and darkness closed over the ship like an ebony lid. The captain, his face gray with exhaustion and care, descended to invite his wife to the wardroom, where he and his first officer sat down to a hurried meal. Ah‑Sam rushed in with the coffeepot and a slab of hard cheese wrapped in a cloth, and then disappeared in his self‑effacing fashion. The captain’s wife poured out the coffee, declining the mate’s offering of tinned meat and soft tack. “Ah‑Sam brought me some lovely broth,” she told her husband. “Did you tell him to do that?”

“I just told him you were green,” he said. “He knows everything there is to know about seasickness.”

“Well, he must, for he has cured me,” she agreed.

When the men were gone, the captain’s wife sat at the table for some time, listening to the fury of the storm and comparing the sensation of being in a ship to that of lying in her bed at home on a tempestuous night. No wonder the sailors were sometimes so contemptuous of landsmen. As the night wore on, she persuaded herself that it was only a matter of time before the storm must abate and she might as well go to bed, as it was impossible to hold a needle, or a pencil, or even a book. She undressed and crawled back into the bunk. After what seemed a long time, but was barely an hour, she slipped into a dreamless sleep.

When she awoke, the room was dark and to her surprise her husband lay by her side, one arm draped across her waist, sleeping soundly. She moved close to him and kissed his cheek. His hand strayed to her thigh, grasped the flesh just above her knee, and pulled her leg over his hip. He whispered her name, nuzzling his mouth against her breasts. The noise of the ship was hushed; the violent pitching and rolling had resolved to a soporific churning that made her think of a child, her child, rocking in his cradle. He was too big for that now. She wandered into sleep again.

Her husband turned over and she did too, so that she faced his back. Now, distantly she heard the clock strike six bells. She opened her eyes to find the room bathed in a shimmering aqueous light. The storm had passed.

She was wide awake, brimming with vitality, but she didn’t move, unwilling to disturb her husband, who had slept so little and had only an hour before he must take up his duties again. She pressed her lips against his back; her drifting thoughts settled on breakfast. Brown bread, plum jam – she’d brought seven jars on board herself – and butter. Oat porridge, hot coffee with heavy cream. I’m starving, she thought, amused by that. How good to be safe, warm, hungry, alive. Her husband groaned in his sleep and a shudder ran down his spine. “Are you awake?” he asked softly.

“I am,” she said. “You’ve got another hour. Go back to sleep.” She eased her leg from his hip as he turned heavily to face her.

“No,” he said. “I’ll get up.”

They were washed and dressed when the steward arrived with the coffeepot, the porridge, and the bread. The captain went on deck to look at his ship, his crew, the sky, and the sea. When he returned she had the table laid with bread, the leftover cheese, her homemade jam and butter, the pot of coffee, the cream, and the squat ewer of porridge wrapped in a towel. “Is all well?” she asked as she poured his coffee, resting her fingers on his neck before turning to her own cup.

“For the present,” he said. “It’s squally to the southeast and we’re headed for it.”

“Can’t we stop?” she asked.

He smiled at his wife’s naïveté, then, sensing that she spoke in jest, turned and swatted her skirt with the back of his hand. “No, miss. We can’t stop. It’s not a horse you’re riding.”

“I want to get out of this cabin,” she said. “I’m dying for fresh air.”

The captain went up first, while his wife put on her cloak and laced her boots. She passed through the wardroom to the hatch, humming to herself, curious to see how the ship would look now, how the sea would look, as they skimmed across it. As she stepped onto the deck, a blast of frigid air blocked her so forcefully she stumbled back, clinging to the ladder rail. Her husband strode toward the mainmast, in conversation with the mate, who gesticulated at something going on in the bow. A wet, white mist, mingling in the sails, obscured her view. She pulled her hood in close, took a few steps from the hatch, and there it was, the sight she had long imagined – at once she lamented the paucity of her imagination – the sea. Slate‑blue peaks studded with white foamy caps, line after line, each wave preceded by another and every one followed by another, as wide as the world was wide, and above it the sky, which was white, flat, and cold, the sun a brighter patch hovering in the distance. There was no visible horizon. She turned to face the bow and there she saw a different sky, the one that worried her husband, a rolling gray above and black below with a band of sickish yellow in between. She couldn’t tell how far off it was, but sky and sea appeared all one, moving rapidly, like a wall of lead, toward the ship.

She breathed in the chilly, salt‑laden air, gazing up at the sailors who were occupied in shortening sail. When she looked back at the deck, her eyes were drawn to a man crouched behind the main hatch, his hands resting on his thighs, his face turned up to her, his eyes narrowed, as if trying to draw a bead on a target. His beard and hair were all black and wild, as were his eyes. In a sudden grimace, he bared a line of fierce white teeth. The captain’s wife stepped back, unnerved, conscious of her accelerating heart rate and a cautionary weakness in her knees. She looked aft, where the helmsman gripped the wheel, his attention fixed on the binnacle. The mist obscured his face. The sea was scarcely visible but made its disposition known; as the hull shifted, the starboard side dropped down and a mass of water rose up, clubbing the side. A tremor of anxiety scuttled up her neck and she felt her upper teeth pressing into her lower lip. There was a new sound, a chugging, pulsing sound, rhythmical and increasing in volume, but she couldn’t tell which direction it came from. Was it belowdecks, or in the dark water below that?

She returned to the aft ladder, pausing to look toward the bow in hopes of seeing her husband. Another sea shipped over the deck, washing so forcefully across the planks that no sooner had she turned to see it than she was standing ankle deep in seawater. The helmsman, knocked off his feet, scrambled back to his post without comment.

What was that sound? Surely it was coming from the sea. Or was it the sky?

A man high in the rigging shouted. A sailor on deck was sprinting, as best he could, toward the mate, who was bent over near the mainmast. Another shout went up in the rigging. “Sail‑ho,” she heard. “Look to your stern.”

The mate leaped away from the man who was screaming, and as he too attempted to run along the tilting deck, he called out, “Hard down your wheel.” Again she turned to see the helmsman, who whirled the wheel with all his strength. Following his astounded eyes she saw what he saw, and as she gasped at the sight, she heard the helmsman’s strangled cry, “She’s on top of us.”

First it was the bowsprit, parting the mist, carried high on the running sea and aimed directly at the port quarter, and then, far above, the enormous reefed yards that seemed to reach out like arms to gather in everything in their path. Screams from the men rent the air, and the thrumming rose to a fever pitch. The great bow, now visible, dived into the waves between, and the yards came about, angling toward the brig’s stern. The captain’s wife, frozen on the deck, had a moment in which hope and fear collided and her overtaxed brain, solving at last the mystery of the rhythmical droning, tossed out the useless information that the oncoming vessel was a ship‑rigged steamer. Up came the bowsprit again, well above the main deck, the bow rising nearly vertical behind it, so it appeared the steamer intended to leap over this unexpected obstacle, another ship. Then it paused, and for an excruciating moment in which no one spoke and all were suspended in a soundless void, it was as if the universe itself drew in and held a startled breath. In the next, as the sea gathering beneath the steamer’s hull reached its peak and commenced its inevitable decline, the bow came surging forward and down, folding the Early Dawn ’s bulwarks like pasteboard, shattering the wardroom skylight, and with a deafening roar, still driving mercilessly forward, rammed the bowsprit up to the stem against the mainmast of the helpless brig.

The captain’s wife saw none of this. With the first breach of the bulwarks she was knocked off her feet and hurled facedown onto the deck, where, like a pin before a ball in a ten‑pin alley, she was summarily rolled into the scuppers. She landed on her back with her left leg twisted beneath her. Above all the noise, the shouts of the officers, the shriek of steel rending wood, the roar of the steamer’s engine, she heard the pop of her ankle as the tendons gave and the small bone cracked. She lifted herself on one elbow but fell back, covering her eyes with her hands, for she saw that the mainmast was tilted and sailors were sliding off the yards into the sea like turkeys in a morning mist. Why did she think of turkeys? She had seen them once, just at dawn, raining from the maple trees on the lawn outside her bedroom window, awkward and calamitous, complaining in their harsh, croaking voices.

The captain, believing his wife to be still in the cabin, made his way to the stern, shouting orders as he went. He clambered across the wreckage of crates, casks, shards of broken glass, lumber, rope. Above him he could hear the panicked sailors on the steamer deck, but he couldn’t see them. He pushed his way past what he recognized as a section of the deckhouse and his heart misgave him, but then he spotted something blue flapping in the scuppers. It was his wife’s woolen cloak. He called her name and she cried out for his aid. In a moment he was kneeling beside her, pulling her into his arms, pressing her cheek to his breast. “My ankle is broken,” she said. “I don’t think I can stand on it.” The captain rose, drawing her with him. “Lean on me,” he said. “We’ve got to get you in one of the boats.”

From the forecastle, men swarmed onto the deck, rushing this way and that in response to orders from the officers. Not many minutes had passed since the call of “Sail‑ho,” but time stretched now with an arbitrary elasticity – there seemed to be a great deal of it – and it was with a sense of agonized relief that every ear greeted the cessation of the steamer engine’s monotonous drone. Again an eerie silence came upon the sea. The steamer had gouged the Early Dawn ’s hull down to the waterline and she was taking on water above and below. As the sea rose and fell, both ships were pushed and pulled deeper and deeper in a fatal embrace from which there was no escape.

Just that moment of silence, harshly punctuated by the mate shouting the order to abandon the ship, and then the men were scurrying, hauling water kegs and sacks of pilot bread to the ship’s boats, making harried trips back to the forecastle to grab a pipe, a loved one’s picture, a good luck charm. The first boat released from the cradle swung outboard on its davits, as the ship shuddered and the deck shifted. The captain’s wife, leaning on her husband’s arm and hobbling toward the stern, took heart at the practiced industry around her. The panic of the collision was over and now the business of the sailor tribe, whose god was the sea, was to accept the verdict of their deity and prepare their ship for sacrifice. “There are enough boats for us all,” her husband reassured her. “You’ll be on the first one.”

“I want to stay with you,” she protested.

“That’s not possible, darling.”

Determined to plead her case, she looked up at him and their eyes met. His confidence – in himself, in his command, in his crew, in her – banished her fear and buoyed her up so resolutely that she gave up her suit. “I know,” she said.

Two sailors, steadying the boat and handing down oars to two others standing in the bow and stern, hailed their approach. “This way for your missus, sir. All comforts provided,” one said boldly, but in a manner so cheerful amid the wreckage of all their hopes, that the captain’s wife laughed and her husband smiled. As she made ready to be handed into the boat, she comforted herself with the thought that her darling son, her Natie, was safe at home.

From above, on the steamer deck, the shouts of the men escalated, followed abruptly by the ominous, distinctive sound, low and threatening at first, like a rumble from the earth’s core, then rising in pitch: the outraged complaint of a wounded tree tearing itself apart. All eyes turned to the mainmast, which was slowly folding, its yards cracking like sticks on the deck below. The captain’s wife turned to her husband, but as she did the sky tilted, the deck rose up beneath her feet, the boat she was poised to enter shifted toward the sea, and a flood of water rushed in upon her, knocking her to her knees. She heard her husband call her name, but she couldn’t see him, she couldn’t see anything. The cold water lifted her up, up, over the bulwarks and then dashed her down with such force that her cloak was torn from her shoulders and her legs flew up before her as if she had been dropped from a tower.

She struggled, holding her breath and pulling her limbs into her body, but two forces were ranged against her – the ever‑downward pressure of gravity and the relentless pull of the deep. As she was carried down she had no conscious thoughts, only her visceral mind fought for life. She opened her eyes, looking for light, but there was only cold and soundless darkness.

The storm advanced upon the shipwreck, first caressing it with a delicate spray, a tentative swell, a distant thunderclap. The sailors in the boat, now suspended at an angle, the bow lower than the stern, clung to the manropes for dear life. The captain had been washed into the sea with his wife, and two sailors on the deck were occupied cutting life rings from the taffrail and throwing them over the lee side. Others readied a second boat, their eyes wildly scanning the water for any sign of their lost commander. “He’s there,” cried the mate, pointing to the chop beneath the broken mast. And it was true; the captain had surfaced. He turned round in place, desperate to find his wife. “Do you see her?” he shouted to the men gathered above. A well‑aimed preserver hit the water just beyond him, but he ignored it. “Save yourself, man,” the mate called back. But the captain, a skillful swimmer, continued treading water, turning in place, straining to see through the rain and the rising sea. “She’s there,” he cried, striking out toward the bow. He made out something there, something darker than the sea.

The mate hung over the rail, thinking, Don’t be a fool, but then he too spotted the dark thing floating and the captain approaching it, cutting through the water with powerful strokes. He had reached it, he grasped it, and a cry escaped him as he gathered it into his arms. It was his wife’s blue cloak.

Again he treaded, turning in place. She must be near. Another life ring flopped into the sea close to the steamer’s hull. In desperation, the captain dived beneath the surface. She must be there, between the two ships. He could see nothing. It was futile, but how was he to give up? He dived again, swimming with froglike strokes beneath the surface.

On the Early Dawn , the sailors in the boat had succeeded in cutting through the tackle and one cried out, “She’s going!” as the small craft plummeted into the waves. The captain, rising up to take a breath, felt a blow across his shoulders that knocked the remaining air out of his lungs and pushed him cruelly back down. When he tried to rise again, something solid blocked his way. There was no air left in his lungs; he could feel his eyes bulging with the effort not to breathe. He sensed a light behind him and turned toward it. Then, with what terror and sadness he understood that he was looking down, that it was his wife, her pale face raised to his, her hair streaming like spilled ink over her shoulders, her arms opened wide, rising toward him from the depths, coming to meet him, to take him with her, having preceded him, only moments before, entirely out of this life.

Date: 2015-02-16; view: 882

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Construction managers must understand contracts, plans, specifications, and regulations. | | | THE GREEN BOOK |