CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

GRAYSON

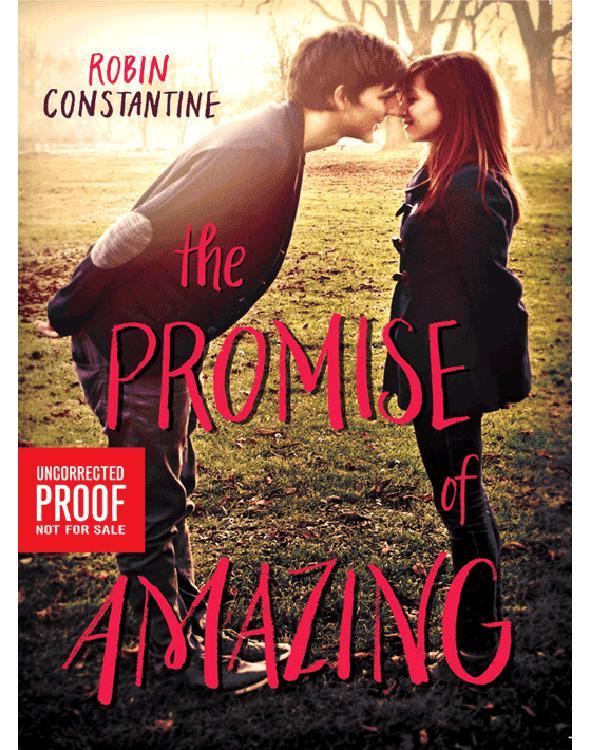

Robin Constantine

The Promise of Amazing

The Promise of Amazing

By

Robin Constantine

ONE

WREN

“NONE OF YOU ARE GOING TO HARVARD.”

Mrs. Fiore paused for effect, scanning the faces in my Honors Lit class with a smug smile. She’d delivered the words with such conviction, it was as if the dean of admissions called and told her that no girl from the entire junior class of Sacred Heart Academy would even be allowed to apply to Harvard.

This was supposed to be a pep talk.

It was a rainy, miserable Friday in November. The kind better suited to burrowing under a comforter watching a Gossip Girl marathon than being dissed by your guidance counselor. My chances of going to Harvard, or any college for that matter, were on the fringes of my mind. The future was a faraway idea that came after more pressing ones, like Thanksgiving break or the gamble of putting a deposit down for junior prom by the December deadline without a date prospect in sight.

I surveyed the class, wondering if anyone else found this speech irritating. Resigned eyes stared straight ahead as Fiore droned on. Next to me, Jazz took notes. Across the room in the back corner, Maddie had her head down, pencil in hand. It looked like she was taking notes too, but I could tell she was sketching. I hoped I wasn’t her subject this time, because the look on my face was anything but pretty.

Honestly? Harvard had never been a passing thought, even as a reach school, but to hear someone, a guidance counselor no less, tell me it wasn’t a possibility made my mind reel. Was this some sort of Guidance 101 mind trick? Didn’t Mrs. Fiore realize she was insulting us?

I imagined recording her little speech. I’d strap her into one of our ass‑numbing desks and demand proof of her guidance degree, since it was painfully clear she must have skipped the How to Inspire Your Students seminar in favor of the Dowdy Floral Prints and the Many Ways to Rock Them workshop. Then I’d force her to listen to that condescending drivel over and over again and see how inspired she felt afterward.

Fiore’s proclamation added another depressing dimension to what was fast becoming my semester of discontent. My current class rank was an unimpressive forty‑nine. Forty‑freakin’‑nine out of one hundred and two, which technically put me in the top half of the class but barely . And my application for the Sacred Heart National Honor Society was a total fail. Nominated but denied. To add to the humiliation, the teachers felt compelled to let you in on the reasons why you didn’t get in, so you could improve and work harder to make it the following semester.

Wren Caswell. Doesn’t participate in class .

Bright but quiet .

Quiet. Quiet .

Too quiet .

I tried not to let the evaluation bother me, but it did. Being quiet was not a conscious protest. It was my nature. And once that sort of “Wow, you’re quiet!” klieg light was forced on me, it drove me deeper into my shell. If I had something to say, well, yeah, I would say it, but I never went out of my way to call attention to myself. In school this had always been a good thing. Applauded, even. The NHS evaluation made it sound like a character flaw. Something I could improve.

That’s just not how it worked.

“What was up with Fiore today?” Jazz asked, peeling away the plastic wrap from her baby carrots and fat‑free dip. Jazz was training to run her first half marathon with her father in January and had adopted a clean‑eating philosophy. Lately she ate the same lunch–lean protein on sprouted‑grain bread, a Vitaminwater Zero, baby carrots and fat‑free dip. It had never bothered me, but today, after the No Harvard speech, I resented its wholesome overachieving perfection.

“Thank you. You thought she was out of line too?”

“Oooh, who’s out of line? What did I miss?” Mads plopped down her lunch tray on the table.

“Fiore. Last class, or were you dozing again?” Jazz asked, pointing at her with a baby carrot. Mads leaned over, grabbed the carrot out of Jazz’s fingers with her teeth, and chewed as she shimmied her chair closer to the table. With her close‑cropped platinum hair and devilish grin, she looked like a naughty, private‑school Tinkerbell.

“Not dozing, doodling,” she said, grabbing a sketchbook from her pile of books and sliding it to me.

“You were doodling Ben Franklin?”

“No.” She grabbed the book and flipped to a different page. “That was yesterday. Here, from before.”

“Oh, um . . . who?” I asked, handing the book to Jazz.

“You can’t tell?”

Jazz peered at me over the sketchbook, brows raised in question.

“Some guy from a boy band?” I guessed.

“No! Zach,” Mads said, taking the book from Jazz.

“Ah, should have known, very Cro‑Magnon like,” Jazz said, dipping another carrot.

Mads scrunched her face but smiled. “I suck at noses. It’s all in the shading. So what about Fiore?”

“You know, that whole ‘none of you are going to Harvard’ thing,” I said.

“Oh, that ? What’s the big deal?” she asked, popping open her bag of baked chips and offering me one. I waved them away.

“I don’t like to be talked down to,” Jazz said.

Mads shrugged. “She’s a realist, that’s all.”

“I can get in to Harvard if I want,” Jazz countered.

“Okay, so maybe you can, Dr. Kadam, but what about the rest of us? Harvard is like a million miles away from here, metaphorically, at least. Why are you both taking it so personally?”

“Because it feels personal,” I said, pushing my brown‑bag slacker lunch away. “It was like she was telling us we’re stupid, so why bother?”

Neither of them responded, and instead shared a knowing look. Mads crunched a potato chip extra loud between her teeth.

“What?”

“This is about NHS, isn’t it?” Jazz asked with the same doe‑eyed face of pity she’d given me when I’d shown her my rejection letter.

“It’s okay to be pissed, Wren,” Mads added.

The pressure of backed‑up tears made me blink fast and look away. Sometimes I hated my friends and how well they knew me.

“That’s not it.”

“Screw NHS, it’s not a big deal,” Mads said.

“It is a big deal,” Jazz protested.

“Jazzy Girl, not helping.”

“You’ll be nominated again next semester. It’s a great thing to have on your transcript.”

They bickered back and forth about the importance of NHS while I zoned out. I knew NHS was a big deal. It was the academic elite of the school. What bothered me most was that damn evaluation that summed me up as the average, quiet girl.

I’d always thought of myself as smart, had no problem making first or second honors, but in a small, competitive school just making it didn’t translate into anything spectacular. My rank had slipped because my brain refused to comprehend higher math. Even with tutoring, I’d taken home my first‑ever Cs in Algebra II and Trig earlier in the semester. As I sat across from my NHS‑accepted pals, I felt like an imposter. Like maybe I’d be better suited to being friends with Darby Greene, who sold her mother’s Xanax for ten bucks a pill in the back of the classroom and didn’t seem to be bothered with less‑than‑stellar grades. Then again, teachers liked her. She spoke up in class.

“Forget it, really, I’m okay,” I finally said.

“And why should we be taking guidance from a woman who buys her hair color off the shelf at Duane Reade?” Mads asked. “Come over after school. I’ve been dying to practice those ombré highlights on your hair. Zach and his friends can drop by. We’ll hang in my basement.”

Zach was Madison’s overgrown pup of a hook‑up buddy. They had about zero in common, except they couldn’t keep their hands to themselves when they were within three feet of each other. She’d been trying to share the wealth by setting me and Jazz up with his pals, but so far Zach’s friend pool was about as bland as the baked chips Mads was noshing.

“If ‘hang in your basement’ is code for fighting off whatever soccer teammate Zach has with him this week, I’ll pass, but I’ll take a rain check on the highlights,” I said.

“How ’bout a movie night?” Jazz suggested. “I reserved Pretty in Pink at the library. I could pick up something else too, make it a double feature? Big bucket of air‑popped popcorn? I’ll even splurge with peanut M&M’s.”

“That sounds great, but–”

“Wait,” Mads said, “so both of you would choose cheesy, canned romance and junk food over flesh‑and‑blood, six‑packed‑out‑the‑ass soccer guys?”

Jazz’s dark eyes turned incredulous. “Cheesy? Canned romance? Pretty in Pink is a classic–”

“–that I’ve seen chopped up on basic cable about umpteen times.”

“Guys, I have to work,” I said, trying to snuff out their fantasy‑versus‑reality debate.

“What’s the fun in being the owner’s daughter if you can’t skip out now and then?” Mads asked.

“We’re booked solid this weekend. Besides, the Camelot may be my future.”

Jazz looked between Maddie and me. “Since when?”

“Weddings are big business. It wouldn’t be a bad thing, right? I wouldn’t need major math skills to run it. I could hire someone for that.”

“Sure, and then you could hire me fresh out of Pratt to give the place an overhaul,” Mads continued. “And Jazz could have her huge Bollywood‑style wedding there, and we’ll all live happily ever after.”

“Why am I the one getting married in this scenario?”

“Because I’m the architect, and Wren is the business owner, and I wasn’t sure how a pediatrician would fit into the whole thing. Besides, I want to wear a sari.”

“Four years of medical school plus a residency, ha, I’ll never have time for a real romance.”

“It’s just an option I’m tossing around. Not everyone has such a clear picture of their life after high school,” I said, balling up my uneaten lunch. The PB&J squished like Play‑Doh in the brown paper bag.

“What about after work, Wren? You’re usually done by eleven, no?”

“Dunno. I think I’m just gonna lay low this weekend.”

“You’ve hooked up with someone like, what, once, twice, since the Trevor hump‑and‑dump? Come on, ditch work for one night. You’re overdue for some fun.”

“Madison,” Jazz reprimanded her in a whisper.

I gathered my books and trash and pushed back from the table. “Stop telling me what I need, ’kay?”

“Wren, wait, sorry. Trev’s the idiot. All I’m trying to say is it’s time to get your feet wet again . . . well, among other things.”

“Mads, really,” Jazz said, chuckling.

“Use it or lose it. Zach’s friends are hot. You never know, you could be cozying up with the next David Beckham.”

“Yeah, I’ll give that some thought . . . not ,” I said, walking away before either of them could say anything else.

One slight mention from Mads and–zap –Trevor DiMarco was back in my head. I was over him, but I wasn’t exactly over us . He was my first. My only. My cautionary tale.

He’d been a friend of my brother, Josh. One of the many guys that hung around our house, playing basketball in the driveway or sitting around our living room watching Comedy Central and wasting time until they figured out what sports event or party they were hitting that night. The revolving door of cute boys was a perk of having an older brother at St. Gabriel Prep, and I took full advantage during Josh’s senior year. Inventing reasons to be in the kitchen. Doing my homework on the deck. Anything to inconspicuously put myself in the middle of the action.

Trev called me Osprey. Seagull. Raven. Every bird name except Wren. But I never took his teasing to be anything more than that. Until the night I looked up from Wuthering Heights and saw that Josh and the others had left. Trev stood in front of me, hands in pockets, shoulders hunched to his ears, his blue eyes slightly timid, unsure. Something I’d never seen in him.

“Hey, Wren,” he said, taking the book out of my hand as he leaned against the island. My stomach knotted up when he said my name. I hadn’t even had the chance to bookmark my page. “I was thinking, maybe . . . would you . . . how about . . . wanna hang with me tonight?”

“Here?” My voice was tight as I drummed my fingers on the counter. He’d never made me nervous before, but now that we were one‑on‑one, it hit me upside the head. He was the reason I hung around so much. Trev, with his perfect sandy hair, perpetual tan, and laid‑back attitude had gotten to me. He cupped his hand over mine to stop the drumming.

“Why don’t we just, you know, roll where the night takes us?”

“Roll where the night takes us” was Trev’s life philosophy, and I couldn’t get enough. Our relationship was a dizzying blitz of prom, graduation parties, and endless nights rolling wherever life took us, and while sometimes it only led us to the lumpy futon in his family room, it was exotic to me. I was gone, gone, gone–caught up in the rush of being in what felt like my first serious relationship. With Trev starting SUNY Purchase in the fall, I knew we had an expiration date, but it wasn’t something we talked about. Part of me even held on to the hope that maybe we wouldn’t have to end.

None of that was on my mind, though, as we rolled into Belmar one gorgeous day in mid‑July. The sun was warm, the breeze was cool, and I was having my first‑ever hand‑in‑hand walk down the beach in the surf with a guy I truly cared about. Then we had that conversation.

All Trev said was that he couldn’t believe he’d be at orientation in less than a month. All I said was that I couldn’t wait to visit him in the fall, how I’d work it out somehow, take a bus or a train or hitch a ride with Josh when he went up to see him. Then we walked in silence. His grip loosened slightly, and he kept looking at me like he wanted to say more. The longer the silence, the more I realized I’d said too much, but I never thought he’d dump me right then as a biplane with a banner that read One‑Dollar Shots and Half‑Price Apps–D’Jais! sputtered by overhead.

“Baby, no, I thought . . . well . . . I want to be free when I go to school. You should be free too. I thought that was sort of . . . understood.” The tone in his voice was sweet, almost concerned. I knew this breakup wouldn’t bother him–this was something he was just rolling with, like everything.

That was the last day I saw him.

I tried to be casual about the whole thing, worldly, but it wasn’t how I was wired. Hump‑and‑dump, well, yeah, that felt about right.

With my mom already at work and my dad stuck on a case at the prosecutor’s office, I had to walk the ten blocks crosstown to the Camelot. I raced down our front steps, bracing against the raw dusk air, and stared wistfully at my sister Brooke’s Altima, which sat idle in our driveway since she was away at law school. Four more months until my road test, and then it was mine. Tonight I didn’t mind the walk. At least the rain had stopped, and the exercise helped shake off my grumpy mood.

The Camelot had been in my mother’s family for forty‑five years. Every celebration, from my grandparents’ golden wedding anniversary to my sweet sixteen, had been held in one of the Arthurian‑inspired ballrooms. When the Camelot opened in 1967, it was the place to have a wedding. Now only the lobby retained the kitschy medieval charm, with dark wood, burgundy drapes, and an oil painting of King Arthur (which insiders knew was my great‑grandfather posing as him) over a working stone fireplace. One suit of armor, a six‑foot monolith Josh had named Sir Gus, presided over the entrance to our main ballroom, the Lancelot.

None of us were ever forced to work, but there was an unspoken expectation that we would pitch in when we hit high school. Brooke had worked around her studies and social life. Josh, on the other hand, had turned the Camelot into his social life when he was on, recruiting friends and transforming the back room into a party between courses. I filled in here and there through sophomore year, but now, since both Brooke and Josh were away at school, I took on a full weekend schedule when necessary.

As I breezed through the front doors, the chaotic energy of wedding prep gave me an instant lift. I’d been joking with Jazz and Mads, but maybe it wouldn’t be so crazy for me to take over in the future. I already knew the business like the back of my hand, and I definitely had opinions on what worked and what didn’t. I’d even helped my mother pick out colors when we gave the ballrooms much‑needed makeovers. Since Brooke was in law school and Josh was . . . well, doing whatever he was doing at Rutgers, it was a sure bet that neither of them was interested. The Camelot, right under my nose, might be my calling. I knocked on the doorjamb to my mother’s office before strolling in, ready to share my recent epiphany.

She slammed down the phone and fumbled with a bottle of ibuprofen before shaking out two little orange pills.

“You were supposed to be in twenty minutes ago,” she said, popping them into her mouth and washing them down with a swig of water from the bottle on her desk.

“I’m sorry. I had to walk,” I answered, whipping off my coat and pulling down the sleeves of my starched white work shirt. My underarms were damp. I did a quick sniff test. Clean.

“I didn’t mean to snap at you, Wren,” she said, rubbing her eyes and leaning back in her rolling chair. The wall of her office was covered with forty‑five years’ worth of framed thank‑you letters and pictures of smiling couples. Mom looked harried. The weight of the world or, more precisely, the weight of every wedding and event, sat on her shoulders.

“Well, I’m here now,” I said.

“If one more thing goes wrong tonight, I’m going to jump ship myself. The florist is running late, Chef Hank is complaining about the quality of the salmon, and Marguerite and Jose called in sick. We’re seriously understaffed for this wedding tonight. Any chance Jazz or Madison would want to earn some extra cash?”

“I think they’re already out,” I said, tightening my messy French knot.

“Then you’d better hustle, sweetie. Cocktail hour starts in less than thirty minutes,” she said, standing up and reaching for her suit jacket.

I hurried into the Lancelot to find a dozen or so black‑and‑white‑clad Camelot staff assembling table settings with more silverware than any modern‑day person needed. Eben saw me and grinned.

“Hey, ’bout time you showed up.”

Twenty‑one and working his way through culinary school, Eben Phillips had started at the Camelot around the same time as my sister, Brooke. He was practically part of the family and hands down my favorite work bud.

“Check this out, charitable donations as favors,” he said, handing me one of the cards.

In lieu of little glass swans or bars of chocolate with their names on them, the couple had donated money to a charity that distributed mosquito nets to needy families in Africa.

“Cool. That’s one I’ve never heard of,” I said. “Need help?”

“I’ll be your bestie for life if you take over,” he said. “I’m assigned the head table tonight, and they’re in Guinevere’s Cottage. I have to get over there, like, yesterday, to make sure everything is in order.”

“Lucky. Can I be your second in command?” I asked, batting my eyelashes.

Cocktail hour at the Cottage was always fun because it was like being at the epicenter of the party. You caught a glimpse into the lives of the couple and their friends as they rehashed the ceremony and took silly photos. The change of scenery also made the night go faster somehow.

“Aww, baby, maybe if you had your butt here on time. I already picked the new guy,” he said, motioning with his chin over to a tall, blond boy who appeared confused as to how to arrange the water goblets.

“New guy? Come on,” I said. “But I guess it’s not his skills you like.”

“Um, don’t go there, Baby Caswell. I’m not into jailbait,” he said. “You’ll just hafta sling those cocktail franks yourself tonight, darlin’.” He handed me the box with the rest of the engraved donation cards and summoned Clueless Blond Boy to follow him across the parking lot to the cottage.

By the time I’d finished setting out the favor cards, there were guests in the lobby waiting for cocktail hour. I closed the curtains on the glass doors to the ballroom so the big reveal would be more dramatic and made my way to the frenzied kitchen to pick up a serving tray for the first round of hors d’oeuvres. I waited and watched as others walked by with platters of mini quiches, fried ravioli, and shrimp‑cocktail shooters, getting a sinking feeling about what I’d get stuck serving.

Chef Hank pushed a tray of cocktail franks toward me. I reluctantly grabbed it and made my way to the already bustling ballroom as the opening strains of the wedding band’s version of “Fever” echoed through the back room.

Little hot dogs were the bane of my existence. On my first day serving, when a guest asked what they were, I felt like saying, “Duh, are you blind?” but instead came out with “Tiny batter‑wrapped kosher frankfurters with dipping sauce” in a formal voice that Eben never let me live down.

“The proper name is cocktail frank , but I like your style,” he told me, after he composed himself in the back room.

“I was just trying to make them sound . . . I don’t know, more impressive.”

“Call ’em whatever you want. They’re the height of tacky, but everyone gobbles them up faster than you can say, ‘Mustard with that?’”

Since then, whenever a guest asked that idiotic question, Eben and I made up some lavish‑sounding name to make the lowly cocktail frank sound classy. The hot dog game was more fun when the two of us were working the same room. I was not in the mood.

When I ran the Camelot, they would be banished from the menu.

I put on my cheek‑busting service smile and wandered into the crowd, offering the tray to anyone who looked interested. It wasn’t long before I ran into the other bane of my existence at work: the group of rowdy guys. They were the ones at a wedding who made obnoxious jokes, drank too much, and flirted with anything that had a pulse.

“The Weenie Girl!” bellowed a ruddy‑faced man in a brown suit.

Rowdy guys who gave me a nickname: a special breed. At least I knew they wouldn’t ask me what I was serving.

“Not a party till the wieners come out!” someone else said as thick hands emptied the tray, leaving nothing behind but grease stains and crumbs on the paper doily. I went back to the kitchen, hoping to snag more trendy hors d’oeuvres like crab‑cake sliders or raspberry Brie bites. Instead I watched helplessly as Chef Hank gave me more of my vile food nemesis.

“You really hate me, don’t you?”

He saluted and busied himself with the next server.

Back in the Lancelot, I took my time weaving through the crowd, ducking here and there and trying to avoid the Rowdies.

“Hey, Weenie Girl!”

People actually turned to look at me. I froze, embarrassed from the shouted nickname and the laughter it provoked. My face cramped from smiling. I walked slowly toward them, but all I wanted to do was throw the tray Frisbee‑style across the room and let them deal with the fallout.

“Grayson, just the girl you’re looking for,” said the brown‑suit man.

The person in question spun around and flashed a dazzling, white‑toothed grin that made me want to fix my French knot. He was younger than the rest of them, with dark, jagged hair that fell into his eyes. I held up the cocktail franks to him, softening my smile and praying he wouldn’t ask any questions, since his appearance had completely short‑circuited my brain.

“Sweet. Watch this,” he said, grabbing at least five dogs.

He tilted back his head, threw one of the hot dogs high in the air, and caught it in his mouth to the applause of the surrounding group. While chewing he kept his eyes on me, maybe wondering why I wasn’t cheering along with the rest of them. I should have left, but there was something about the way he oozed confidence while acting so asinine that fascinated me. He was a complete tool, but I bet no one ever accused him of being too quiet.

For his next trick, he threw two weenies in the air at once and successfully caught them in his mouth, to the delight of his rapt audience. This time, when he brought down his chin, he wasn’t grinning. The rest of the hot dogs fell from his hand, and he gestured frantically toward his neck.

No one in the group thought he was choking for real. The brown‑suit man pounded his fist against a nearby table and chanted, “Gray. Gray. Gray.” Gray’s face blossomed into a bright shade of red, and drool spilled out of the corner of his mouth. My first thought was that if he would go to those lengths for a joke, he must be a real asshole. I was about to leave when I saw the animal‑like panic in his eyes.

I dropped my tray and wrapped my arms around him from behind. The words fist, thumb in , right above the navel came out from the recesses of my brain, and I squeezed upward several times to no avail. Someone yelled for help. There was desperate movement around me, but I continued pushing my fist into Gray’s abdomen until I felt his body release. Just as the band finished playing “The Girl from Ipanema,” a gooey mass tumbled out of his mouth and landed with a splat on the cocktail table in front of him. Someone groaned. Gray gripped the table, head down, and coughed. Sound. A good sign. My arms fell from around his waist, and I stepped back.

His navy‑blue jacket stretched taut across his back with each breath. Brown‑suit guy put a glass of water in front of him, but Gray waved it off. He stood up straight and turned toward me, mouth dropped open like he had something to say.

His dark brown eyes held mine for a second. Open. Honest. Longing . As if the hot‑dog‑tossing tool was just some mask he’d put on for the party. A wave of recognition coursed through me. Did I know him? No. I’d never seen him before . . . but . . . I took a step toward him.

He blinked and lurched forward.

“Are you okay?” I asked.

Then he hurled all over my black Reeboks.

TWO

GRAYSON

REGURGITATING ON SOMEONE’S SHOES IS NOT the best way to make a first impression.

Especially after that someone saved your life.

I wiped my mouth along the sleeve of my suit jacket, eyes zeroing in on her black sneakers and the puddle of upchuck around them. The noise of the room was smothered by the ba‑bum, ba‑bum of my heartbeat in my head–a jagged zigzag of pain. The Weenie Girl was a statue of calm shock, mouth slightly open, brows knit, as her eyes went from the pool of vomit on the floor to my face.

I was breathing, and it was a miracle.

“Grayson?”

Hands were on me. Voices urged me to sit. A chair slid underneath me, and I flopped down onto it. All the while my eyes remained on hers. She brushed some stray hair away from her face, tucking it behind her ear. The distance between us closed, and it was just . . . her. And me. Calm in the chaos. The hair tumbled across her face again. My fingers ached to sweep it away. I wanted to say something, but for once words wouldn’t come. Then Pop blocked her from view.

“Grayson, are you all right?”

They all thought I’d been joking. So, okay, pretending to choke would have been some smart‑ass spectacle I might have pulled, but I doubt I could have been so convincing.

He clapped his hands in front of my face.

“What, Pop?” I croaked. His weathered brow creased as he tugged me to standing.

“You need some air,” he said, gripping my forearm. We knifed through the crowd made up of the extended Barrett family, always ready for a party. I craned my neck, searching over the sea of animated faces for the Weenie Girl, but she was gone.

Pop led me through glass doors into the dark lobby. The doors glided to a close, muffling the band’s campy rendition of “I Get a Kick out of You.” He took me to a quiet corner, right next to a shiny suit of armor, which was so out of the ordinary, it made the whole episode more surreal. My head throbbed.

“Grayson,” he said.

“Pop, I’m fff–” I began, but got distracted by the rise and fall of party noise as the doors to the ballroom opened again. Weenie Girl . But no, it was my stepmother, Tiffany, sauntering over holding a martini glass filled with bright blue liquid.

“What happened?”

“Nothing, I’m fine,” I said.

“It’s not nothin’,” Pop said. “He almost choked to death.”

She let out a high‑pitched squeak and placed her martini glass on the stone mantelpiece.

“Grayson Matthew, are you okay?” she asked, one hand running through my hair, the other on my cheek, as she gave me a once‑over. Tiff liked to use my middle name for emphasis when something significant happened. I’d heard it a lot in anger after I got tossed out of St. Gabe’s last spring. This soft version, almost a whisper, was something new, and I felt myself falling into it.

“I’m fantastic,” I said, shrugging her off. “Can’t we just go back in?”

“Gray, you’re loopy. I’d feel better if you got checked out. We can hit the ER and be back before they cut the cake,” Pop said.

Tiff ruffled. “Let me get my coat and say some good‑byes.”

“Tiffany, no. You stay. Mingle,” Pop said.

She put her hand to her chest and sighed. “Are you sure?”

“Yep. Gray and I will be filling out paperwork and fannin’ our balls at the ER. Nothin’ we can’t handle.”

I stifled a laugh and winced, my throat still raw.

“Really, Blake, do you have to be so crude?” Tiff asked.

“C’mon, you love me,” he said, pulling her in for a kiss so intense, I felt like a perv for witnessing. When your father gets more action than you do, it’s all sorts of wrong. Like natural selection gone awry.

They were rubbing noses as a woman in a dark suit walked up to us. She tucked a strand of short blond hair behind her ear, folded her arms, and waited uncomfortably until Pop and Tiff broke apart.

“Are you the boy who choked?”

The Boy Who Choked . Pretty much summed up my seventeenth year.

“Yes,” I answered.

She turned to Make‑Out Master Blake Barrett. “I can call the paramedics if you want. I’m–”

“No, that won’t be necessary. We’re going to the emergency room,” Pop answered, cutting her off. Her eyes widened, and she tucked her hair behind her ear again. There was something vaguely familiar . . .

“You have a daughter,” I said.

“Grayson, are you okay?” Pop asked.

“She works here,” I continued, ignoring him.

“Yes. Wren. Do you know her?”

“She saved my life.” The phrase sounded strange, dramatic as it hung in the air.

“Really? I was downstairs checking on another event. The minute I heard I came up. I’m still not quite sure what happened.”

Pop gave her the no‑nonsense “he choked on a hot dog, and your daughter did the Heimlich” version, making it sound less epic than it felt. He left out that he’d been at the bar at the time and that my uncles had watched like a panicked Greek chorus while a complete stranger took control of the situation.

A beautiful stranger with a name.

Wren .

“Please, send me the ER bill,” Wren’s mother said, handing Pop a business card. We were interrupted by a waft of cold air as a vision of white burst through the front door.

“Uncle Blake!”

My cousin Katrina swished across the lobby in her poufy white dress. Pop turned to us and made a short cutting motion with his hand across his throat that I could easily interpret. Shut your trap. The bride doesn’t want to know someone almost died at her wedding .

“Trini, you’re a vision,” he said, kissing her cheek.

“The ceremony was so touching,” Tiffany chimed in.

I stood back, feeling about as useful as a bobblehead. A brown‑haired bridesmaid, who I’d seriously eye‑fucked during the wedding vows, waved to me. Two hours ago the adrenaline surge from flirting had made me rethink my foray into monkhood. I hadn’t been with anyone since . . . Allegra. A wedding reception where everyone was juiced up and ready to party seemed like a prime moment to get back in the action.

Now it didn’t matter. I was more interested in Wren’s mother and the waiter she was talking to who’d come in behind Katrina. He put a hand up to his mouth, nodded, and disappeared into the ballroom. I was about to follow, hoping he could lead me to Wren so I could say thanks, or what’s up, or whatever was the appropriate thing to say to a person who saved your life, when Pop tugged my sleeve.

“C’mon, Gray.” He waved and mouthed something to Tiff as the wedding party rustled into formation, lining up to make their grand entrance. The pretty bridesmaid tapped my shoulder as we brushed past them.

“Dance later?” she asked. Her glossy lips promised sweetness and warmth. A familiar rush, the thrill of being with a new person, made me pause. Then I thought of Wren; her body pressed against my back, soft but strong, and fighting for me. Even though I’d done jack shit to deserve it.

“No, I’m heading out,” I said, and followed Pop into the brisk autumn evening.

Pop paused at the top of the stairs and fumbled around with a cigarette case and lighter. The business card fell from his pocket. It whirled helicopter‑style and landed on the bottom stone step.

“I hate weddings. Here, help me,” he said, cigarette dangling from his lower lip. He handed me the lighter and cupped his hands against the breeze coming off the bay. I ran my thumb across the spark wheel until it flickered with a pop. He sucked in, making it look painful. The tip of the cigarette glowed orange. I tossed him the lighter, and he tucked it back into his jacket.

“You should quit, Pop,” I said, watching him exhale a long stream of smoke.

“Yeah, yeah, I know. That and eat bran fiber. They’re on my list,” he said. “C’mon.”

At the bottom stair, I picked up the business card.

“Here, you dropped this.”

“Don’t need it.”

“But . . . she was nice,” I said, feeling oddly protective.

“Nice?” Pop said. “Gray, she was covering her ass. She doesn’t want to get sued. Not that I would do that to the Caswells.”

“You know her?”

“No, not her,” he answered, shaking his head. He took a hard hit from the cigarette and blew out another deliberate smoke stream. “Jimmy Caswell was first string on St. Gabe’s with me. We took ’em to a championship that year.”

“You never mentioned him,” I said, running my finger across the engraved letters on the card.

Ruth Caswell

Proprietor–Banquet Manager

The Camelot Inn

“Lost touch after high school. He’s an attorney with the city now. Thrown a few clients my way, but that’s as far as it goes. Why so interested?”

“No reason,” I lied, sliding the card into my wallet. “Pop, I don’t need to go to the hospital.”

“Yes, Grayson, you do.” A jet‑black Mercedes chirped and lit up as we walked toward it. Pop’s leased wheels to impress potential home buyers. “You’re acting weird. And your mother will be all over me if I don’t take you somewhere to get checked out.”

My mother lived with her new family in a galaxy called Connecticut. It had been six years since their amicable split, but Pop still kissed her ass whenever it concerned me, as if one wrong move would send the divorce police swooping in to demand I live with the more responsible parent. Getting kicked out of St. Gabe’s had made it worse, like it had been Pop’s fault. Sometimes I wanted to shake him and yell, Stop being a pussy! and other times, I completely got it. No one did disappointment better than my mother.

“Why do we even have to tell her, Pop? I’m fine.”

“She still talks to some of the family, Gray. All I need is for her to hear this from someone else–”

“Pop, who saw? Uncle Pat? The way he’s drinking, he probably won’t remember anyway. Come on, let’s go back in.”

He took another drag, then flicked the cigarette to the ground, grinding it out with his foot.

“I can’t go back in there. The walls are closing in around me. Weddings are such a farce.”

“Says the man on his second marriage,” I said.

“That’s different. There was none of this bullshit,” he said, gesturing toward the Camelot. “Just us. City hall. Garbage pie at Denino’s afterward. Remember?”

Getting fresh air had given me a second wind, a desire to go back inside, but I knew Pop would stand his ground. Maybe it was better if I didn’t go back. Wren was probably somewhere hosing off my DNA from her shoe. That’s not something you get over quickly. There’d be another opportunity to meet her, and if not, I’d invent one.

“You know, garbage pie sounds really good. Probably the same wait time at Denino’s as the ER. What do you say, Pop?”

“The Barrett boys on the lam. You sure you feel okay?”

“Never better.”

“You drive,” Pop said, tossing the keys.

I caught them, focusing on the task at hand instead of the gut feeling that meeting Wren was the start of something important. I shook it off as I slid into the driver’s seat.

She’s just a girl, Grayson .

A girl who saved my life.

I wanted to sweep the hair away from her face, feel her body against me, without an audience or the threat of my imminent death.

Connecting with her had felt different .

Real.

I had to get to know her. At least I had her name. Wren Caswell . The rest would be easy.

It was what I was good at.

THREE

WREN

I STARTLED AWAKE. THE CLOCK ON MRS. FIORE’S wall was ten minutes behind. Every time the second hand reached the number six, it would stick and make a loud clicking noise for a few seconds before continuing its journey around the clock face. With its brown shag carpet and orange vinyl chairs, the dark paneled office made me feel like I’d been transported back to the seventies. The fact that, for a few seconds, time actually did stand still didn’t help.

As an addendum to the inspiring None of You Are Going to Harvard speech, each junior had “Three sessions of thirty!” to strategize her chosen path. “Three sessions to chart out a map to the future!” the posters in the hallway read, making the future sound like something you could find with a compass and guide dogs.

At least I’d been pulled out of chem lab, my last class on this very sleepy Monday.

Mrs. Fiore returned, the aroma of coffee wafting behind her. Probably announced to the faculty lounge as she was getting her java fix: “That quiet girl, Wren Caswell, is sitting in my office–like she’s going to get in anywhere . How can she be Brooke Caswell’s sister? Now, hers was a high school résumé with achievement written all over it.” I straightened out of my slouch as she placed the mug of coffee on her blotter. The mug had a picture of one of those saucer‑eyed Precious Moments kids on it with the words God Don’t Make Junk underneath.

She tapped her keyboard a few times then angled the computer screen so I could see. My name, “Caswell, Wren,” was in bold blue lettering at the top of an empty form of some kind.

“So, Wren, where should we begin?” she asked, putting on a tiny pair of half glasses with zebra‑print frames.

The truth was, I wanted to like Mrs. Fiore. I wanted to have one of those relationships you see on TV where the guidance counselor is your buddy and you can drop by her office on a whim, just to say hi, and she helps you out of some ridiculous predicament involving laxative‑laced bake‑sale brownies while the laugh track murmurs in the background. I wanted to be one of those students who had a teacher as a friend, someone who really “got” me, but I clammed up the moment I was around anyone in authority. What was there to talk about except school and the weather? Not exactly the stuff of great bonding.

“I don’t have a clue,” I finally answered.

“That’s pretty exciting. The world is open to you then, isn’t it?”

All except Harvard .

“It’s overwhelming,” I answered.

So overwhelming, it was easier not to think about. I thought I wanted to continue with school, but unlike Jazz, who was gunning for Cornell to follow her mom, or Maddie, who was determined to go to Pratt and become the next Frank Lloyd Wright, I never had my sights on anything so specific. Not law, like my father and Brooke. Josh seemed to like Rutgers, but was that a reason to go there? The stark reality of my average grades made me wonder if maybe my path was elsewhere. Did I really need a college degree to run the Camelot? What if I started straight out of school? Would Mom want me to?

“Well, that’s why we’re having these sessions. You have to reframe that overwhelmed feeling. Take charge. Do you plan on going to college?”

“I . . . um . . . maybe?” I answered. “I’ve been thinking there might be something different for me.”

Her eyes looked bewildered as she peered at me above her zebra frames.

“What do you mean?”

“Well, what about, say . . . Mark Zuckerberg, the creator of Facebook? He dropped out of college and he’s a bazillionaire, no degree necessary. Or what if I don’t even know what I want to pursue, but I fall into it, like that guy on the insurance commercial . . . the one who made the Vatican out of toothpicks?”

“The Vatican out of toothpicks?” she asked, glancing over her shoulder at the defective clock.

“Yes. Not that I’d do that, I just, well . . .” The words spilled out of my mouth one after the other before I could stop them. I was derailing. A flush crept up my neck. “Well, my family owns a catering hall, the Camelot. I was thinking I could run that someday.”

This was something she could grasp on to; the smile returned to her face. “Business, maybe? Or are you more interested in the hospitality part of it?”

“Not sure.”

“Well, we can evaluate your interests and test scores and see where that leads. Here’s the password to your account,” she said, scribbling down a series of letters and numbers on a paper and handing it to me. “Start by taking the personality assessment. We’ve got incredible capabilities with our new computer programs; you can use some of your study periods to research schools, even schedule visits. We can also see where your application can be ramped up. . . .”

I tried to process all the information, but by the end of the thirty minutes I was more confused than ever. I promised to research at least three schools I’d like to apply to next year and made an appointment for my second visit in February, which felt light‑years away.

Jazz waved when I walked back into the chemistry lab with ten minutes to spare. I mimed hanging myself with a noose and let my tongue loll out of my mouth.

“That good, Miss Caswell?” Sister Marie asked.

I truly sucked at the teacher/student‑bonding thing.

“So what did you talk about? Does she grill you about your personal life?” Jazz asked as we left school for the day and walked down the long driveway next to the building.

“No, thank God.” I imagined Mrs. Fiore’s reaction to the cocktail‑frank incident at work this past Friday. “Saving Grayson.” What an amazing topic for your personal essay! How did you know what to do? What were you thinking? The attention of my coworkers was more than I could handle. Even Jazz and Maddie were floored when I told them. As odd as it sounded, I had no clue how I pulled that set of skills out of my ass. I’d learned about the Heimlich maneuver in health class and had passed the poster on the wall in the Camelot more times than I could count, but neither one really prepared me for the reality of having someone’s life in my hands.

“Just stuff about school,” I continued. “I have to research colleges. Think about how I can possibly shore up the holes in my high school career.”

“Since when is going to high school a career?” asked Maddie, panting as she ran to catch up to us.

“Mads, you sound a little breathless there,” Jazz said. “You should come with me on my interval runs.”

“No, Wren and I are doing the yoga thing. Maybe you should join us?”

“When does that start again?” I asked.

“The Thursday after Thanksgiving.”

“I work at my mom’s office on Thursdays,” Jazz said, “but maybe I could try a class sometime. I’m always so tight after my long runs. Doing both is a great way to cross‑train, Mads. Just tossing that out there.”

“I can think of better ways to cross‑train. Let’s toss out something more interesting, like how we’re going to spend Thanksgiving break.”

“Easy. I’m working,” I answered.

“No,” they both said.

“Yes.”

“What about the Turkey Day game? All those college boys home from school . . .” Mads trailed off as though she were envisioning a stadium full of hot guys.

“C’mon, Wren, it’s tradition,” Jazz said.

The annual Turkey Day game between St. Gabe’s and Bergen Point High was Bayonne’s version of the Super Bowl. Everyone went to cheer on the two bitter rivals, the prep boys and the public scrubs. Bergen Point usually wiped the field with St. Gabe’s defensive line, and there was always an undercurrent that the game was more a battle of classes than of school teams. Sacred Heart girls were supposed to cheer for our unofficial brother school, but Jazz, Mads, and I went more for the eye candy–prep, scrub, anything in between–didn’t matter, we didn’t take sides. This year, though, I wanted no chance of seeing Trevor home for the holidays. Huge stadium, small world–it would be just my luck to run into him and do something stupid like dribble hot chocolate down my peacoat. Not. A. Chance.

“Maybe,” I lied, offering them some hope as we reached the end of the drive and emptied out into Sacred Heart’s thrumming social hub . . . aka the street in front of school.

“Hey, Weenie Girl!”

No. Way.

“Wren, did that guy just call you Weenie Girl ?” Mads asked, picking up her pace as she realized what was happening. “Omigod, that’s Puke Boy, isn’t it? You didn’t accurately convey how friggin’ hot he is!”

Sure enough, two cars away from the driveway stood Grayson, leaning against a crappy beige convertible with a darker tan soft‑top. The car was worn and pale, like it had been out in the sun too long, but there was something about it. A car with character. It made him more approachable.

Maddie sauntered up to Grayson, said something to make him laugh, and waved us over.

“Wren, this is so Pretty in Pink . . . totally Blaine hacking into Andie’s computer and sending his picture,” Jazz whispered, taking hold of my elbow.

“Stop,” I said, trying to tame my smile, because seeing him here did feel as unreal as a movie moment, but I didn’t want to be that obvious.

Grayson looked younger than I remembered. His hair was a tousled mess, with those jagged bangs hanging in his eyes, and he wore this retro‑style blazer with patches at the elbows that he somehow managed to make look cool. He had an eyebrow piercing by his left eye–something I hadn’t noticed at the wedding. And there was that grin again. A dazzling sun drawing me into orbit. The attempt to control my smile was futile.

“Sorry, I couldn’t resist yelling that,” he said as I reached him. “Besides, we were never formally introduced.”

“Wren Caswell,” I said, white‑knuckling the strap of my messenger bag as if it were a lifeline. God, I wished I’d had the time to pop a piece of gum in my mouth.

“Grayson Barrett.”

Jazz poked me.

“Oh, um, this is my friend Jazz, and you already met Maddie,” I said, gesturing to her while she scrutinized Gray’s car. From the curl of her upper lip I could tell she wasn’t impressed–at least not with his ride.

“Jazzzzzzzzz,” he said. Jazz loosened her grip on my arm and giggled. “I like it.”

“How are you feeling?” I asked.

“I’m breathing, so it’s all good.”

A girl called out his name, he shrugged one shoulder in greeting, and then it dawned on me. How stupid could I have been? He wasn’t there for me. This was just a coincidence.

“Well, I guess I’ll, um, see you,” I said, backing away.

Gray’s brows drew together. “Oh, I . . . I came to see if you felt like getting a coffee or something,” he said. “I mean, that’s if you, well, can I give you a ride home at least? You too, Jazz, Maddie, if you want.”

“Awfully nice of you, Grayson, but we love the party atmosphere of the Boulevard bus–all that BO and rubbing up against perfect strangers,” Maddie said, ushering a still‑Grayson‑struck Jazz toward the crosswalk. “You two kids have fun.” Maddie mouthed, Call me! waving her cell in the air.

When I turned back to Gray, his eyes gleamed with amusement. I was hyperaware of the mass exodus of Sacred Heart, the urgent rush of girls on their way home and the passing seconds of silence between us. I missed Maddie and her quick quips already. Why was I just standing there? Mute?

Gray’s smooth voice broke the silence.

“So, Wren. Do you have to go home?”

Grayson opened the passenger door for me and I slid in, picking up the book on the front seat. Plato’s The Republic . I fanned through the pages. There were highlights and ink scrawls in the margins of the first half.

“Light reading?” I asked, handing it to him as he got in.

He tucked the book into the front pocket of his backpack then hoisted it to the backseat. “For a class.”

“Really? Where?” I asked. Could he possibly be a college guy?

“Saint Gabe’s.”

Grayson wore faded denim jeans and a well‑fitted white Henley tee under his jacket that I caught myself admiring for too long–not the usual St. Gabe’s khaki‑and‑button‑down uniform.

“Well, the class is at Saint Gabe’s,” he continued as the engine grumbled to life. “I go to Bergen Point. They don’t offer philosophy.”

The car was immaculate–no wrappers or soda cans. He even had a Yankee Candle air freshener, Home Sweet Home, dangling from the rearview mirror. I spun it gently with my index finger.

“Let me guess: Mom?” I asked, smiling.

“Nope. All me. Can’t a guy have a good‑smelling car?”

“Sure, why not?” I didn’t have much experience with guys and cars, but my brother, Josh’s, could probably be condemned it was so gross, and Trev’s . . . ugh, why was I even thinking of him?

He pulled out of the spot, driving slowly until we hit the first red light about a block away. I’d forgotten to roll my skirt after school and it sat at dweeb length, an inch above my knee. I crossed my legs, hoping to subtly show a little more skin. Grayson noticed.

“So what were you saying–you go to Bergen Point but take a class at Saint Gabe’s? I didn’t know you could do that,” I said, thoroughly enjoying snagging him.

He flustered, ran a hand through his hair. “Um, oh, philosophy . . . yeah, you can’t. I was supposed to take the class this year. Figured I’d just go through it on my own.”

“So you were at Saint Gabe’s?”

Yep, up until my junior year.”

“Maybe you know my brother. Josh Caswell? He graduated last year.”

He nodded. “Everyone sort of knows everyone at Saint Gabe’s, right?”

“Why’d you leave?” I asked.

The light changed to green, but he hesitated, gripping the wheel, until an insistent beep from behind got his attention.

“They kind of asked me to leave. Listen, why don’t we go somewhere? It’s not the kind of thing I want to talk about while I’m driving. I can’t see your face,” he said, giving me a sidelong glance that made me bite my lower lip.

“Okay,” I said, trying to calm the hormonal rush that had just surged through my body.

“How about that coffee? We could grab one and hit the park. It’s warmish. Any place you like?”

“Starbucks at South Cove?”

He grunted.

“I don’t do pretty coffee. I know this hole‑in‑the‑wall deli with the best French roast around. You’ll love it.”

“Sounds good,” I lied. Coffee–pretty, French roast, or otherwise–tasted like battery acid to me, but I didn’t feel like mentioning it. Especially after he told me about leaving St. Gabe’s. Awkward . I wasn’t sure if the torqued‑up feeling in my gut was attraction or a warning sign. I just knew I didn’t want to go home yet.

A tinny‑sounding bell announced our entrance as we walked into the deli. The guy behind the counter beamed at Grayson.

“My man, where’ve you been?”

“Spiro, how’s it hanging?” Grayson answered, walking behind the counter to pour our coffees. Spiro clapped Grayson on the back, gave me a once‑over, and whispered something to him. They both chuckled. Heat nibbled my earlobes. I waited, expecting some sort of introduction, but Gray handed me the to‑go cup.

“Cream and sugar’s over there if you need it,” he said, turning back to Spiro. I added enough cream and sugar to my coffee to make it taste like Häagen‑Dazs and tried to catch what I could of their hushed convo. . . . Tough break . . . brinker . . . a friend . Grayson joined me at the counter to put a lid on his coffee. When I reached into my bag for some cash, he stopped me.

“Wren, please, a coffee for a life. It’s the least I can do,” he said, pulling out a few bills from his pocket.

“Thanks,” I murmured, concentrating on clipping my messenger bag closed. My brain completely fogged over with the way his voice wrapped around my name. I stuffed the feeling down. Whether he was hot or not, I still had no clue what he wanted from me.

“So what should I tell Lenny if he asks for you again?” Spiro asked, handing Grayson the change. Gray shoved it in his pocket and ushered me toward the door. The bell jangled as he held it open for me.

“Tell him I’m out of the game,” he said, the door closing behind us. When our eyes met, Grayson simply said, “Business.”

Out of the game? Business? What sort of business could he possibly have at a deli?

By the time we reached the park, the sun was already setting, casting an orange glow across the horizon. Gray found a spot by the boat pond, and we shuffled through fallen leaves to a vacant bench. Two squirrels quarreled noisily and chased each other up a tree. After their chattering died down, the park was silent except for the occasional footfall of passing joggers.

“So how did you know where to find me?” I asked, determined to keep my thoughts straight.

“I have my ways,” he said low, raising his eyebrows a bit. My expression must have showed the ripple of uneasiness I felt, because he laughed.

“That sounded creepy, sorry. Your mom gave us her card. That’s how I got your last name. I asked around. Not exactly differential calculus,” he said, leaning back and slinging his elbow over the top of the bench so he was partially facing me. I huddled my hands around my coffee cup, letting the steam tickle my nose, wanting to know why he was “asked to leave” St. Gabe’s but not sure how to bring it up casually.

“You’re too polite. Don’t you want to know why I got kicked out of school?” he asked.

“I guess,” I said, surprised he’d read my thoughts. “Wasn’t sure if it was too personal a question.”

“Wren, you’ve already had your arms around me from behind. I think we’re past the ‘too personal’ stuff.”

“Ha, good point,” I said, burning up at the thought of how intimately I’d already touched him. I blew on the rim of my cup, avoiding his gaze. “Okay, then why’d you get kicked out?”

He closed one eye, wrestling with the best place to start his story, then took a deep breath and said, “I was a term‑paper pimp.”

I coughed, nearly choking on the coffee. “Pimp?”

He smirked at my reaction. “No, seriously. I was a middleman. Matched people up with the right guys–I had specialists in chemistry, history, creative writing; some at Saint Gabe’s, some elsewhere. Some I did myself. I got sloppy. Someone tipped the principal off. A guy handed in a term paper that was too good. They threatened him with expulsion and nabbed me.”

“Didn’t anyone else get in trouble?”

“A few of my customers got suspended, but I didn’t rat out my suppliers. I wouldn’t do that,” he said. “That’s why they really kicked me out–because I wouldn’t rat.”

I didn’t know what to say. Here I was, afraid to be even one second late for school, and he was so willing to admit–to brag, even–about his total disregard for what anybody with a shred of conscience would know was just . . . wrong. He studied me, waiting for more of a response. He didn’t seem embarrassed or regretful at all.

“Didn’t you worry you’d get caught?” I asked.

“At the time I didn’t really think about it. I had a lot going on.”

A lot going on, like what? I wanted to ask, but did I really want to know? Maybe I would have felt differently about our chat if I hadn’t been obsessing about my own crappy school record lately. The unfairness of it all bothered me.

“But . . . you knew it was wrong.”

“Wrong is such a subjective term, don’t you think?”

I tried to laugh, but it came out flat. “No. Pretty black‑and‑white.”

“It wasn’t the smartest thing to do, but . . . think of it like this–in the real world, people outsource all the time. Some of my customers had jobs on top of their school workload. There was a demand; I filled it. Simple. Econ 101. At least that’s how I defended myself. They didn’t quite buy it, hence getting the boot.”

Grayson’s argument was so convincing, I was almost swayed.

“Well, it is different than outsourcing,” I said.

“Wren, Saint Gabe’s is a wild place. There are guys whose parents make more money than we’ll see in our collective lifetimes, and then there are guys on scholarships whose families are barely scraping by. The ones who can’t buy their way into college? Good grades are the strongest weapon they have. They needed a business like mine. I felt like I was helping people.”

“I guess it’s just something I would never do. I’ve waited until the last minute to write term papers, but no matter how shitty, at least they were mine.”

“Wow, you’re such a Girl Scout.”

He’d turned into the hot‑dog‑tossing tool again . . . or maybe he always was and his quirky car and inviting smile duped me into dropping my guard. I wasn’t that far from home; I could walk. I stood up and tossed my coffee into a nearby trash can.

“Well, um, thanks for the coffee, the ride, but I’ve got to go.”

I began walking away, then realized I’d left my bag in his car. “I need my bag.”

Grayson frowned as he poured the rest of his coffee into the dead leaves. He stood up, tossed the cup into the trash, and walked toward the car. I followed behind, taking two steps for every one of his brisk strides. When he reached the car, he opened the passenger side, stooped in for my bag, and held it out for me. My fingertips grazed his as I took it from him.

“Guess you’re thinking, Why’d I save this asshole?” he said, leaning against the car.

Our eyes met. The tool was gone. And there it was–that longing–like right after I’d saved him. What did he want from me?

“God, Grayson, no, I’m not thinking that at all,” I said, taking a step back from him.

“Then what are you thinking?” he asked, flipping his bangs out of his eyes with a toss of his head. In that second all I was thinking was how charming he looked when he did that. Wren, get a freakin’ grip!

“You hit a nerve, okay? I’m royally screwing up this semester, and I hate it but not enough to cheat. I totally feel all that bullshit pressure to get good grades. And I’m not. Not like my friends,” I said, all the stuff I couldn’t admit to Jazz and Maddie came rushing out in one long breath. “Why do we even have to be judged by rank? What does that measure? All my number says about me is that I’m average. And to top it off, I’m supposed to know what I want to do with my life, but I know I won’t ever get into Harvard, so hey, at least that’s one thing I can cross off the list.”

“You’re applying to Harvard?” Gray asked.

I huffed. “Just forget it,” I said, turning away from him. Leaves rustled beneath my feet, punctuating the rush of my exit. He trotted next to me to gain ground, then stood in my way. I tried to go around him, but he kept dodging in front of me. I stopped, staring up through the canopy of half‑barren branches. The sky was a deep shade of dusky blue. It would be dark soon.

“Wren, please,” Gray said, putting his face in my line of vision, hands up in surrender.

“I have to go,” I said, ducking under his arm. He grabbed my elbow, so I spun back to face him.

“Why did you save me?”

The question stopped me. I wrenched my arm free. “You were choking?”

“I know, I just . . . but why did you step in? If it had been me, and the situation was reversed, I don’t think I would have stepped in.”

“So . . . you’re telling me you wouldn’t have saved me ?”

He ran a hand across his face. “No, that’s not what I meant . . . not you, personally, I mean anyone. I wouldn’t have known what to do.”

“Sure you would have. Simple. Health 101.”

“Okay, I guess I deserve that,” he said. “I’m just saying I would have panicked. I did panic. I thought I was a goner until you stepped in.”

“Someone would have helped you,” I said.

“Maybe, maybe not. All I know is you did,” he said, putting his hands in his pockets. “I guess what I want to say is thank you for saving my life.”

A jogger trotted by. I crushed some leaves under my foot, letting what Grayson said sink in.

“This is weird, isn’t it?” I said, stepping away.

“What?” he asked.

“I feel like I know you, but I don’t,” I began. “It’s like we had this intense moment, but . . . it’s over, isn’t it?”

“It doesn’t have to be,” he said, “does it?”

I rubbed my hands together, folded my arms across my chest. “I think I’d better get going.”

“Sure,” he said, taking his keys out of his pocket. “Let me take you home.”

Date: 2015-02-16; view: 850

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Bad Medicine | | | GRAYSON |