CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

How to Teach English 6 page

There are three areas we need to know about in the pronunciation of English - apart from speed and volume - which are intimately connected with meaning.

| Pronunciation |

Sounds (phonemes) are represented here by phonetic symbols (/b/, /i:/ and /k/ for example). This is because there is no one-to-one correspondence between written letters and spoken sounds. Thus the c’ of cat’ is pronounced differently from the c’ of‘cease’, but is the same as the c’ of‘coffee’. ‘Though’, ‘trough’, and ‘rough’ all have the ‘-ou-’ spelling but it is pronounced differently in each case. Different spellings can have the same sound too: plane’ and ‘gain’ both have the same vowel sound, but they are spelt differently.

By changing one sound, we can change the word and its meaning. If we replace the sound /bl with the sound /m/, for example we get ‘meat’ instead of ‘beat’. And if we change /i:/ to /1/ we get ‘bit’ instead of ‘beat’. A complete list of phonetic symbols is given in Appendix C on page 191.

Stress: the second area of importance is stress - in other words, where emphasis is placed in words and sentences.

The stressed syllable (the syllable which carries the main stress) is that part of a word or phrase which has the greatest emphasis because the speaker increases the volume or changes the pitch of their voice when saying that syllable, e.g. ‘important’, ‘complain’, ‘medicine’ etc. And in many longer words, there is both a main stress and a secondary stress, e.g. interpretation, where ‘ter’ has the secondary stress and ‘ta’ the main stress. In addition, different varieties of English can often stress words differently. For example, British English speakers usually say ‘advertisement’ whereas some American speakers say ‘advertisement’. The placing of stress can also affect the meaning of a word. For example, ‘import’ is a noun, but ‘import’ is a verb.

In phrases and sentences, we give special emphasis to certain parts of the sentence (by changing our pitch, increasing the volume etc), e.g. ‘I’m a teacher because I like people’. But we could change the meaning of the sentence by placing the stress somewhere else, for example, ‘I’m a teacher because I like people’. You can imagine this being said as an angry response to someone asking a teacher to do something terrible to their students. If, on the other hand, the sentence is said with the main stress on the word ‘I’ it is suggested that this is what makes the speaker different from others who do not like people.

Teachers use a variety of symbols to show stress, e.g.

□ □ n • • •

'teacher performance rapport engagement

Pitch and intonation: pitch describes the level at which you speak. Some people have high-pitched voices, others say things in a low-pitched voice.

When we pitch the words we say, we may use a variety of different levels: higher when we are excited or terrified, for example, but lower when we are sleepy or bored. Intonation is often described as the music of speech. It encompasses the moments at which we change the pitch of our voices in order to give certain messages. It is absolutely crucial for getting our meaning across. The word ‘Yes’, for example, can be said with a falling voice, a rising voice or a combination of the two. By changing the direction of the voice we can make ‘Yes’ mean ‘I agree’ or ‘Perhaps it’s true’ or ‘You can’t be serious’ or ‘Wow, you are so right’ or any number of other things.

Teachers often use arrows or wavy lines to show intonation tunes (pitch change), like this:

You're jx5Tan^Kyf>u:e yj/u? or YoIT^oTo^jTfCTo^^you?

| Conclusions |

In this chapter we have

• made it clear that this short chapter is only the briefest introduction to a huge subject and suggested that it should be read in conjunction with the Task File on pages 148-152.

• studied sentence construction, showing how sentences are constructed of and from subjects, verbs, objects, complements and adverbials.

• looked at aspects of nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, determiners and conjunctions.

• noticed that a grammatical form or a word doesn't guarantee its meaning. Words and structures can have many meanings just as similar concepts can be represented by different forms or words.

• examined the differences between speech and writing. Each has its different characteristics and students need to know about these. As teachers, part of our job is to expose students to written and (spontaneous) spoken English.

• looked at three aspects of pronunciation: sounds, stress and intonation.

•

| Looking ahead |

• In the chapters on reading and writing (7 and 8) we will pay attention to the special features of writing we have discussed in this chapter.

• In the chapter on listening (10) we will look at taped examples of spontaneous speech and talk about how students can be helped to deal with them.

What does language study consist of?

| w to teach guage |

How can we help students to understand meaning?

How can we help students to understand language form? How should students practise language?

Why do students make mistakes?

How should teachers correct students?

Where do language study activities fit in teaching sequences?

| What does language study consist of? |

In the sections that follow, we will analyse each of these issues in some detail in the light of the study of the following areas of language: the verb ‘to be’ + noun (e.g. ‘It’s a pen), simple invitations, the use of comparative adjectives, and the word ‘protection’.

To get an overall idea of the teaching procedures envisaged for each language point, readers can turn to page 64 where we show how Study fits into teaching sequences. Before that, however, we will look at the four Study issues (listed above) in detail, giving examples in each case for the language points being discussed.

| How should we expose students to language? |

Example 1: It's a pen' (complete beginners)

The teacher is with a group of complete beginners. She wants them to be able to say what objects are called. She holds up a pen, points to it and says ‘pen ... look ... pen ... pen’ as many times as she thinks it is necessary. The students have had a chance to hear the word.

Later, she may want to go beyond single words. She can hold up the pen and say ‘Listen ... it’s a pen ... it’s a pen ... it’s a pen’. Once again, she is

giving students a chance to hear the sound of the new language before they try to use it themselves. Later still, she may start asking the question ‘What is it? (pointing to the pen) ... What is it?’ so that students get a chance to hear what the question sounds like.

Because many people acquire languages by hearing them first, many teachers prefer to expose students to the spoken form first (as in this example). However, some students may need the reassurance of the written word as well.

Example 2: invitations (elementary)

The teacher wants her elementary students to be able to invite each other and respond to invitations. She plays a tape on which the following dialogue is heard.

sarah: Joe! Hello. joe: Oh hello, Sarah.

sarah: Umm. How are you? joe: Fine. Why?

sarah: Er... no reason ... {pause ... nervously) Are you doing anything this evening? joe: No. Why?

sarah: Would you like to come to the cinema?

joe: Yes, that would be great. Well, it depends. What's on?

sarah: The new Tarantino film.

joe: I suppose it's all violent.

sarah: Yeah. Probably. But it's meant to be

really good. joe: I don't usually like violent films.

sarah: Oh. OK. Well, we could go to the

pizza place or something. joe: I'm only joking! I'd love to come.

The teacher plays the tape more than once so that students get a good chance to hear the invitation language - some of which (the present continuous, vocabulary items) they probably already know. She may also say the invitation part of the dialogue herself and she may feel it is a good idea to show the students a written version.

Example 3: comparatives (lower

intermediate)

In this example for lower intermediate students, the teacher is going to get students to use comparative adjectives. Before she does this, however, she has them read the text opposite.

From Look Ahead 2 by Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter

This text gives students many examples of comparative adjectives used in a fairly realistic way.

Example 4: 'protection' (upper intermediate)

With an upper intermediate class, the teacher wants the students to be able to use the word ‘protection correctly. She shows them the following printout from a computer.

I was married, pregnant; and had a dog for an SPF rating. Now, generally, SPF 2 is low on get wet! These sunscreens do give the best sunscreen after swimming. Use a higher sun exhibited a wide variation in the effective negligence in not providing adequate police free needles will provide any significant Annual 'boosters'... provide inexpensive was of comparable importance. For the farmer her belly. This meagre shelter gives little also responded to the desire of business for jugglers who require an excess of praise and sprays. Your medication may not give absolute Whereat she shrieked and turned to Summers for that citizens might value. Integrity provides everything. There was a mask, a visor for eye to hasten its recovery, began to give it stems from any inadequacies of employment of the villagers but with clothing, food, and of their people and for their defence - and to fall again. My sealskin coat was a good if Mother approves and continues to offer to their ancestors for life and health, and for a diversified line. This provides further scrutiny, the bureaucratic system can provide industry in the country was given increased can't promise you total and utter and complete only in terms of the general need for consumer who have a good record in environmental

protection. 'I dream of your body so luscious protection, but Bergasol's skin type 2 is high protection - after all perspiration can wash protection factor (SPF) on vulnerable spots protection accorded to the import-substitute protection for the city. Several weeks protection. A sufferer from drug addiction protection for your dog against... diseases protection against a severe decline in his protection from either enemies or the wind protection against foreign competition. The protection from hard truths, protection against malaria, some forms of protection. He assured her she need fear protection against partiality or deceit or protection. If it was hot outside it was even protection against the import of foreign foods protection legislation. The employment protection against the sun. But his feelings protection of the environment and the worker protection against the wind and my hands were protection. The ogre's wife hides Jack in a protection against their enemies. When they protection. There is danger that technological protection against allegations of corruption protection. This was simply the first dose of protection. All I can promise is that we can protection, which is encompassed in new clause protection are officially commended and

Edited sample from the Longman-Lancaster Corpus

It shows many examples of the word (in the centre) being used. The examples are taken from a wide variety of sources (books, newspapers, advertisements etc.) which have been fed into a computer. Any word can be looked up in the same way to see how and when it is used. The number of words to the right and left of the search word (the word in the centre) is just enough for us to understand the words meaning and use correctly in each case.

| How can we help students to understand meaning? |

Example 1: 'It's a pen' (complete beginners)

This is perhaps the easiest level at which to explain meaning. The teacher wants the students to understand the meaning of the form pen so she holds up a pen and says pen. The meaning will be clear. She can do the same with words like pencil’, ‘table’, ‘chair’ etc.

When, however, she wants to expose students to the question form ‘What is it?’ she cannot rely on objects. Instead, she asks the question using gestures (raised shoulders and open arms) and expressions (a puzzled look on her face) to indicate the meaning of the question.

Of course, the teacher can also ensure that students understand the meaning of a word by showing pictures (photographs, cards etc.) or by drawing them on the board (even ‘amateur’ stick drawings are useful for this purpose).

Some of the ways of helping students to understand, then - especially when dealing with fairly simple concepts - are: objects, pictures, drawings, gesture and expression.

Example 2: invitations (elementary)

In this example, the teacher starts by showing the students a picture of Sarah and Joe. She gets the students to ask their names and tells them what the names are. Then she asks them to speculate on what their relationship is (‘Do you think they are friends?’) to establish the fact that Sarah likes Joe.

After she has played the tape of the invitation dialogue she can ask them questions to check they have understood the situation, for example:

'What does Sarah want?'

'What language does she use?'

'Does Joe accept?'

'What are they going to do?' etc.

The use of questions like these (often called check questions) establishes that students have understood what the language means.

The teacher could also draw a picture of Sarah with a ‘think’ bubble coming out of her head which says ‘me -> cinema + Joe??!!’

Example 3: comparatives (lower intermediate)

In the Tear of Flying’ text, the teacher can start by asking ‘How does the writer prefer travelling?’ She can then explain the meaning of individual adjectives. She could show a picture of a beautiful sofa and say comfortable’ and follow it with a picture of an old school chair and say ‘not comfortable’. She could then show a picture of a nice armchair followed by the really comfortable sofa and say ‘The armchair is comfortable but the sofa is more comfortable than the armchair’. She could use check questions to see if the students have understood the other comparative concepts, e.g. ‘Which is safer, mountain climbing or watching television?’ or ‘Which is slower, walking or running?’

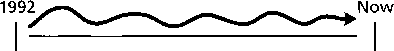

Anything which helps students understand meaning is worth trying. For example, some teachers like to use time lines to explain tenses. The following attempts to show the meaning of ‘I’ve been living here since 1992’ in graphic form.

|

A time line

Example 4: 'protection' (upper intermediate)

The teacher may not need to explain the meaning of ‘protection’ to the students since they can either work it out for themselves (by looking at the computer printout) or check in a dictionary.

Explaining the meaning of abstract concepts is often difficult and time- consuming but it may need to be done. We can explain the meaning of ‘vegetable’ by listing different kinds of vegetable, we can explain the meaning of ‘hot’ through mime (burning ourselves) or by explaining what it is the opposite of. ‘Sad’ and ‘happy’ can be explained by expression, pictures, music etc. But words like ‘protection’ or ‘charity’ are more difficult!

| How can we help students to understand language form? |

As well as hearing/seeing language - and understanding what it means - students need to know how it is constructed, how the bits fit together. Whether the teacher gives them this information or whether they work it out for themselves, they need to comprehend the constituent sounds, syllables, words and phrases of the new language as the following examples show.

Example 1: 'It's a pen' (complete beginners)

When the teacher first says pen she can then show what the sounds in the word are by saying them one by one, e.g. pen ... pen ... /p/ ... Id ... /n/ ... pen ...’. By picking out the bits in this way, she clearly explains the sound construction of the word.

Some sounds can be demonstrated. The sound /p/ for example is made by forcing the lips apart with air from the lungs: the teacher can point to her mouth and show this happening. However, some sounds which are created, at the back of the mouth (like /g/ and /k/) are more difficult to demonstrate in this way.

When the teacher introduces words of more than one syllable she will want to make sure that the students know which syllable is stressed. So, when she says ‘table’, she may exaggerate the ‘ta’ syllable and add even more emphasis by clicking her fingers or stamping her foot on the stressed syllable. When she writes the word on the board, she will indicate which syllable is stressed in one of the ways we looked at on page 50.

The exaggerated use of voice and gesture are also important for demonstrating intonation. When the teacher wants to demonstrate the question ‘What is it?’ she can make the voice fall dramatically on ‘is’ before rising slightly on ‘it’ and she can accompany this by making falling (and rising) gestures with her arm very much like the conductor of an orchestra.

The bits that make up the phrase ‘It’s a pen’ need to be clear in the students’ minds too. One way of doing this is for the teacher to say the bits one by one (just like the sounds, e.g. ‘It is a pen ... it ... is ... a ... pen ... it ... is ....a ... pen ... it’s a pen’) or she can write the following on the board.

| pen. | |||

| It | is | a | table. |

| computer. |

A particular feature of spoken and informal written English is the way in which we contract auxiliary verb forms. We tend to say ‘It’s a pen’ not ‘It is a pen’; we say ‘I’ll see you tomorrow’ not ‘I will see you tomorrow’. This can easily be demonstrated with hand movements and gestures etc. For example, if the teacher makes her two hands into loose fists and shows that one represents ‘it’ and the other represents ‘is’ she can then bring them together to give a clear visual demonstration of ‘it’s’. A similar technique which has been very popular is to use fingers. The teacher points to each of her fingers in turn, giving each finger a word, as in this illustration.

A particular feature of spoken and informal written English is the way in which we contract auxiliary verb forms. We tend to say ‘It’s a pen’ not ‘It is a pen’; we say ‘I’ll see you tomorrow’ not ‘I will see you tomorrow’. This can easily be demonstrated with hand movements and gestures etc. For example, if the teacher makes her two hands into loose fists and shows that one represents ‘it’ and the other represents ‘is’ she can then bring them together to give a clear visual demonstration of ‘it’s’. A similar technique which has been very popular is to use fingers. The teacher points to each of her fingers in turn, giving each finger a word, as in this illustration.

Then she lets students see her bring two fingers together to show the contraction, as in this illustration.

Some teachers use small wooden blocks of different lengths and colours (called Cuisenaire rods) to show word and sentence stress and construction and there are other visual possibilities too: cards, drawings, getting students to physically stand in line as if they were word and sentence elements.

Some teachers use small wooden blocks of different lengths and colours (called Cuisenaire rods) to show word and sentence stress and construction and there are other visual possibilities too: cards, drawings, getting students to physically stand in line as if they were word and sentence elements.

The point of all these techniques is to demonstrate to students how the elements of language add up. So the trick, for the teacher, is to work out what the important features of a word, phrase or grammatical structure are and how the bits fit together.

Example 2: invitations (elementary)

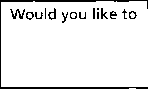

With language like invitations, it may be helpful to treat some consecutive words of the invitation as a single unit. In other words, we can take more than one word and treat them as one chunk of meaning, e.g.

'Would you like to' + verb phrase etc.

'That would be' + adjective

The teacher can then ask students for alternatives for come to the cinema?’, e.g. come to the party/theatre’, ‘have lunch/have a drink’. She can pretend to have one phrase in her left hand ‘would you like to’ and another in the right ‘come to the cinema’ and then draw them together. Or she can write the following on the board.

|

| come to the party? come to the theatre? have lunch? have a drink? |

As with our previous example, the teacher will say the question ‘Would you like to come to the cinema?’ and the answer ‘That would be great’ with exaggerated stress and intonation using gesture and expression to help students understand what the language sounds like.

Example 3: comparatives (lower intermediate)

In the book from which the ‘Fear of Flying’ text was taken, the students are given the exercise on the next page.

Look back at the article and answer the questions.

1 What is the comparative form of these adjectives? safe - safer

safe comfortable convenient cheap slow important good bad

2 What rules can you make about the comparative form of:

a) most short adjectives?

b) long adjectives?

Are there any irregular adjectives which do not fit these rules?

When the teacher asks students to do this exercise she is asking them to discover the construction (of comparative adjectives) for themselves. Both she and the textbook writers think that the students will be able to work it out without having to be told - and that this ‘discovery’ will be more memorable for them than if she simply tells them.

Of course, there’s no reason why a book is needed for discovery activities. Teachers can always ask students to work things out by using their own questions and procedures. What is important is that the teacher should be there to tell them if they have worked out the rules correctly.

The teacher will want to make sure that the students know what a comparative sentence sounds like. She can say ‘Trains are cheaper than planes’ showing through voice and gesture how the rhythm and stress of the sentence works.

Example 4: 'protection' (upper intermediate)

Students clearly need to know how ‘protection’ is spelt and what it sounds like - it is stressed on the second syllable etc. But the computer printout tells us more than that, and the teacher can help students to see what is there.

She can start by asking the simple question ‘What comes before and after the word “protection”?’ and students working together or individually will be able to provide the following answers.

A common pattern into which 'protection' fits is '... protection against + article + noun' but as the printout shows we can also say protection for/from...'.

The verbs which come before 'protection' in our sample include 'provide', 'offer' and 'give'.

Adjectives which commonly come immediately before 'protection' include 'effective', 'complete' and 'environmental'.

As a result of this we can ask students to provide their own table showing where ‘protection fits, for example:

| offer | effective | against | |

| provide | environmental | protection | from |

| give | complete | for |

Or we can encourage students to write protection in their own personal vocabulary books giving the same kind of information, e.g.

protection - offer/provide/give protection against/from/for

Of course, this information is available in good dictionaries, but it is not so memorable, perhaps, when referred to there. Because the students have studied the computer printout themselves - and worked out and discovered facts about the word protection on their own - their understanding of the construction of the word and its grammatical surroundings is likely to be much greater and more profound.

| How should students practise language? |

Practice should not go on for too long, however. There are many other things that teachers and students want to do in classrooms and too much practice will take time away from them.

Example 1: 'It's a pen' (complete beginners)

Repetition can be very useful for students especially at beginner level. It gives them a chance to see if they Ve understood what’s happened so far and if they have, it gives them the confidence to try and use the language themselves.

The simplest kind of repetition is for the teacher to say pen ... pen and then get students to say pen altogether, in chorus. This can be good fun and allows students to try the new word out with everybody else rather than having to risk getting it wrong in front of the class.

After choral repetition, the teacher can ask students to repeat the word individually (now that they’ve had a chance to say it in safety). She calls them by name or points to them or indicates who should speak in some other way and they say the word. She then corrects them if they are not getting it quite right (as we shall see on page 63).

Choral and individual repetition are useful for sentences as well as words. The teacher may well use both techniques for sentences like ‘It’s a pen’ and ‘What is it?’

It is, however, important to move beyond simple repetition during practice. We want students to be able to use a combination of the new grammar with the vocabulary items they have learnt so the teacher gets students to make similar sentences by prompting them with different words, objects or pictures. She may hold up a pen and indicate a student so that the student will say ‘It s a pen’. Then she holds up a pencil and indicates another student so that they will say ‘It’s a pencil’. She can point to the table for the sentence ‘It’s a table’ and so on.

Practice sessions at this level are likely to be a combination of repetition and simple sentence-making of the kind the teacher is using in this example. With different words and constructions, she may not be able to

hold up objects or point to them; instead she can use pictures, drawings, mime, gesture, words etc.

Example 2: invitations (elementary)

As with the previous example, the teacher can get choral and individual repetition of the key phrases ‘Would you like to come to the cinema?’ and ‘That would be great’. When she has done that, she can get one student to ask the question and another student to answer.

Now she can ask students to make different invitations. She can try and elicit alternatives. She can then prompt them by saying ‘concert’ for them to say ‘Would you like to come to the concert?’ and ‘nice’ for ‘That would be nice’. She may also want to give them the option of ‘I’m afraid I can’t’ or ‘No, thank you’.

Date: 2015-02-16; view: 1549

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| How to Teach English 5 page | | | How to Teach English 7 page |