CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

How to Teach English 4 page

There are some exceptions to this, of course, notably in classes where an Activation exercise takes up a lot of time, for example, with a debate or a role-play or a piece of extended writing. In such cases, teachers may not want to interrupt the flow of Activation with a Study stage. But they will want to use the exercise as a basis for previous or subsequent study of language aspects which are crucial to the activity. The same might be true of an extended Study period where chances for Activation are few. But, in both these cases, the only limitation is time. The missing elements will appear, only perhaps later.

The majority of teaching and learning at lower levels is not made up of such long activities, however. Instead, it is far more likely that there will be

more than one ESA sequence in a given lesson sequence or period.

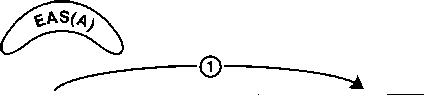

To say that the three elements need to be present does not mean they always have to take place in the same order. The last thing we want to do is bore our students by constantly offering them the same predictable learning patterns - as we discussed in Chapter 1. It is, instead, our responsibility to vary the sequences and content of our lessons, and the different ESA patterns that we are now going to describe show how this can be done.

| How do the three lements of ESA fit together in lesson sequences? |

1Engage: students and teacher look at a picture or video of modern robots. They say what the robots are doing. They say why they like or don’t like robots.

2Study: the teacher shows students (the picture of) a particular robot. Students are introduced to ‘can’ and ‘can’t’ (how they are pronounced and constructed) and say things like ‘It can do maths’ and ‘It can’t play the piano’. The teacher tries to make sure the sentences are pronounced correctly and that the students use accurate grammar.

3Activate: students work in groups and design their own robot. They make a presentation to the class saying what their robot can and can’t do.

We can represent this kind of lesson in the following way.

| Study |

| Engage |

| Activate |

| ESA Straight Arrows sequence Straight Arrows lessons work very well for certain structures. The robot example above clearly shows how ‘can’ and ‘can’t’ are constructed and how they are used. It gives students a chance to practise the language in a controlled way (during the Study phase) and then gives them the chance to Activate the ‘new’ language in an enjoyable way. However, if we teach all our lessons like this, we may not be giving our students’ own learning styles a fair chance. Such a procedure may work at lower levels for straightforward language, but it might not be so appropriate for more advanced learners with more complex language. |

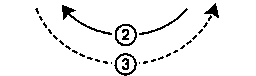

Thus, while there is nothing wrong with going in a straight line - for the right students at the right level learning the right language — it is not always appropriate. Instead, there are other possibilities for the sequence of the ESA elements. Here, for example, is a ‘Boomerang’ procedure.

1Engage: students and teacher discuss issues surrounding job interviews. What makes a good interviewee? What sort of thing does the interviewer want to find out? The students get interested in the discussion.

2Activate: the teacher describes an interview situation which the students are going to act out in a role-play. The students plan the kind of questions they are going to ask and the kind of answers they might want to give (not focusing on language construction etc., but treating it as a real-life task). They then role-play the interviews. While they are doing this, the teacher makes a note of English mistakes they make and difficulties they have.

3Study: when the role-plays are over, the teacher works with the students on the grammar and vocabulary which caused them trouble during the role-play. They might compare their language with more correct usage and try to work out (discover) for themselves where they went wrong. They might do some controlled practice of the language.

4Activate: some time later, students role-play another job interview, bringing in the knowledge they gained in the Study phase.

| Study |

| Activate |

| Engage |

| EAS(A) Boomerang sequence In this sequence the teacher is answering the needs of the students. They are not taught language until and unless they have shown (in the Activate phase) that they have a need for it. In some ways, this makes much better sense because the connection between what students need to learn and what they are taught is more transparent. However, it places a greater burden on the teacher since he or she will have to be able to find good teaching material based on the (often unforeseen) problems thrown up at the Activate stage. It may also be more appropriate for students at intermediate and advanced levels since they have quite a lot of language available for them at the Activate stage. |

|

The two procedures we’ve shown so far demonstrate two different approaches to language teaching. In straight arrows sequences the teacher knows what the students need and takes them logically to the point where they can Activate the knowledge which he or she has helped them to acquire. For the boomerang sequence, however, the teacher selects the task the students need to perform, but then waits for the boomerang to come back before deciding what they need to Study.

Many lessons aren’t quite as clear-cut as this, however. Instead, they are a mixture of procedures and mini-procedures, a variety of short episodes building up to a whole. Here is an example of this kind of ‘Patchwork’ lesson.

1Engage: students look at a picture of sunbathers and respond to it by commenting on the people and the activity they are taking part in. Maybe they look at each other’s holiday photos etc.

2Activate: students act out a dialogue between a doctor and a sunburn victim after a day at the beach.

3Activate: students look at a text describing different people and the effects the sun has on their skin. They say how they feel about it. (The text is on page 75 in this book.)

4Study: the teacher does vocabulary work on words such as pale, fairskinned, freckles, tan’ etc., ensuring that students understand the meaning, the hyphened compound nature of some of them, and that they are able to say them with the correct pronunciation in appropriate contexts.

5Activate: students describe themselves or people they know in the same kind of ways as the reading text.

6Study: the teacher focuses the students’ attention on the relative clause construction used in the text (e.g. ‘I’m the type of person who always burns’, £I’m the type of person who burns easily’). The use of the who’ clause is discussed and students practise sentences saying things like ‘They’re the kind of people who enjoy movies’ etc.

7Engage: the teacher discusses advertisements with the students. What are they for? What different ways do they try to achieve their effect? What are the most effective ads the students can think of? Perhaps the teacher plays some radio commercials or puts some striking visual ads on an overhead projector.

8Activate: the students write a radio commercial for a sunscreen. The teacher lets them record it using sound effects and music.

The patchwork diagram for this teaching sequence is shown on the next page.

|

EAASASEA (etc.) Patchwork sequence

Such classes are very common, especially at intermediate and advanced levels. Not only do they probably reflect the way we learn - rather chaotically, not always in a straight line - but they also provide an appealing balance between Study and Activation, between language and topic. They also give the students the kind of flexibility we talked about in Chapter 1.

| What teaching models have influenced current teaching practice? |

There have been some traditional language learning techniques that have been used for many years. In more recent times, there have been five teaching models which have had a strong influence on classroom practice - and which teachers and trainers still refer to. They are Grammar- translation, Audio-lingualism, PPP, Task-Based Learning, and Communicative Language Teaching.

Grammar-translation: this was probably the most commonly used way of learning languages for hundreds of years - and it is still practised in many situations. Practitioners think that, by analysing the grammar and by finding equivalents between the students’ language and the language to be studied, the students will learn how the foreign language is constructed.

It is certainly true that most language learners translate in their heads at various stages anyway, and we can learn a lot about a foreign language by comparing parts of it with parts of our own. But a concentration on grammar-translation stops the students from getting the kind of natural language input that will help them acquire language, and it often fails to give them opportunities to activate their language knowledge. The danger with grammar-translation, in other words, is that it teaches people about the language and doesn’t really help them to learn the language itself.

Audio-lingualism: this is the name given to a language-teaching methodology based heavily on behaviourist theories of learning. These

theories suggested that much learning is the result of habit formation through conditioning. As a result of this, audio-lingual classes concentrated on long repetition-drill stages, in which the teacher hoped that the students would acquire good language habits. By rewarding correct production during these repetition phases, students could be conditioned into learning the language.

Audio-lingualism (and behaviourism) went out of fashion because commentators from all sides argued that language learning was far more subtle than just the formation of habits. For example, students are soon able to say things they have never heard or practised before because all humans have the power to be creative in language based on the underlying knowledge they have acquired - including rules of construction, and a knowledge of when a certain kind or form of language is appropriate. Methodologists were also concerned that in audio-lingualism students were not exposed to real or realistic language.

However, it is interesting to note that drilling is still popular (in a far more limited way) during the Study phase, especially for low-level students

- as some of the examples in Chapter 6 will show.

PPP: this stands for Presentation, Practice and Production and is similar to the straight arrows kind of lesson described above. In PPP classes or sequences, the teacher presents the context and situation for the language (e.g. describing a robot), and both explains and demonstrates the meaning and form of the new language (can and cant’). The students then practise making sentences with can and can’t’ before going on to the production stage in which they talk more freely about themselves (‘I can play the viola but I can’t play the drums’) or other people in the real world (e.g. ‘My girlfriend can speak Spanish’ etc.). As with straight arrows lessons, PPP is extremely effective for teaching simple language at lower levels. It becomes less appropriate when students already know a lot of language, and therefore don’t need the same kind of marked presentation. A typical example of a basic Pf*P procedure is given in Chapter 6 (Example 1).

Task-Based Learning: here the emphasis is on the task rather than the language. For example, students might be encouraged to ask for information about train and bus timetables and to get the correct answers (that is the task). We give them the timetables and they then try and complete the task (after, perhaps, hearing someone else do it or asking for examples of the kind of language they might want to use). When they have completed the task, we can then, if necessary - and only if necessary - give them a bit of language study to clear up some of the problems they encountered while completing the task. Alternatively, we might ask them to write part of a guidebook for their area. When they have completed the task (which will involve finding facts, planning content and writing the brochure etc.), we can then read their efforts and do some language/writing study to help them to do better next time.

It will be noticed immediately that task-based learning sequences fit very neatly into our boomerang lesson description, where language Activation is the first goal and Study comes later if and when appropriate.

Communicative Language Teaching: this was a radical departure from the PPP-type lessons which had tended to dominate language teaching. Communicative Language Teaching has two main strands: the first is that language is not just bits of grammar, it also involves language functions such as inviting,, agreeing and disagreeing, suggesting etc., which students should learn how to use. They also need to be aware of the need for appropriacy when talking and writing to people in terms of the kind of language they use (formal, informal, tentative, technical etc.).

The second strand of Communicative Language Teaching developed from the idea that if students get enough exposure to language and opportunities for its use - and if they are motivated - then language learning will take care of itself. In other words, the focus of much communicative language teaching became what we have called Activation, and Study tended to be downplayed to some extent.

Communicative Language Teaching has had a thoroughly beneficial effect since it reminded teachers that people learn languages not so that they ‘know’ them, but so that they can communicate. Giving students different kinds of language, pointing them to aspects of style and appropriacy, and above all giving them opportunities to try out real language within the classroom humanised what had sometimes been too regimented. Above all, it stressed the need for Activation and allowed us to consider boomerang- and patchwork-type lessons where before they tended to be less widely used.

Debate still continues, of course. Recent theory and practice have included: the introduction of Discovery activities (where students are asked to ‘discover’ facts about language for themselves rather than have the teacher or the book tell them - see example 4 in Chapter 6); the Lexical Approach in which it is argued that words and phrases are far better building blocks for language than grammatical structure; classroom stages being given new names to help us describe teaching and learning in different ways (e.g. see the reference to Scrivener on page 187); and the study of the difference between spoken and written language to suggest different activities and content on language courses. Further reading on all these is given in Appendix B on page 187.

Whichever way of describing language teachers prefer, the three elements described here — Engage, Study and Activate - are the basic building blocks for successful language teaching and learning. By using them in different and varied sequences, teachers will be doing their best to promote their students’ success.

In this chapter we have

•

| Conclusions |

• described the three elements necessary for successful teaching and learning in class: E (Engage), S (Study) and A (Activate).

• described three different lesson sequences which contain the Engage, Study and Activate elements. In straight arrows lessons, the order is E-S-A, but in boomerang lessons, teachers may move straight from an Engage stage to an Activate stage. Study can then be based on how well students performed (E-A-S). Patchwork classes mix the three elements in various different sequences (e.g. E-A-A-S-A-S-E-A ... etc.).

• talked about different models which people have used to describe teaching such as PPP (Presentation, Practice and Production), Task- Based Learning (which puts the task first and language study last) and Communicative Language Teaching (with its twin emphasis on appropriate language use and Activation methodology).

• seen how PPP is a form of straight arrows lessons, while Task- Based Learning is more like boomerang or patchwork sequences. We pointed out that Communicative Language Teaching was responsible for the modern emphasis on the Activate stages of lessons.

• mentioned, in passing, some of the issues which people are currently debating.

• pointed out that good teachers vary the ESA sequences they use with their students - to avoid monotony and offer a range of learning sequences. The three elements are always present, but in many and different combinations.

•

| Looking ahead |

• In the chapters on reading, writing, listening and speaking (Chapters 7-10) we will see how the teaching examples can fit into different ESA procedures.

• Next, though, we are going to look at what teachers and students need to know about language.

How to describe language

What does this chapter do?

Sentence constructions

Parts of speech

Noun types

Verb types

Verb forms

Pronouns

Adjectives

Adverbs

Prepositions

Articles

Conjunctions and conditionals Forms and meanings Language functions Words together: collocation Speaking and writing Pronunciation

What does this Both students and teachers need to know how to talk about language at

chapter do? various points during learning and teaching. This is not only so that

teachers can explain and students come to understand, but also so that teachers know what’s going wrong where and how to correct it. While it is perfectly possible to learn a language outside the classroom with no reference to the technical aspects of language, in classrooms with teachers it will help if all the participants are able to say how the sounds /b/ (as in ‘berry’) and /v/ (as in Very’) are made, why we don’t say T have 3ccn him yesterday’, or what is wrong with childish-efimc’ when we mean juvenile crime’.

In order to be able to talk about language, we need to know how to describe its various elements. In this chapter, we will therefore look at some fairly basic language descriptions and issues. However, it is

important to realise that a short chapter can only scratch the surface of an extremely complex and challenging collection of different language issues. It can only be a basic beginning to a much much bigger area for investigation. It is intended only as an introduction to some of the terms and issues which teachers and students may need. Teachers must follow up the themes touched on here; indeed they need to have at least one of the grammar books mentioned in Appendix B on page 187 (or an equivalent) on their shelves so that they can learn and investigate further, and as a constant reference work during their teaching lives. In other words, this chapter only introduces concepts which teachers (and students) need to become familiar with and which they will then need to build on in their different ways and at different levels.

In order to work out some of the issues raised in this chapter, it will be a good idea to read about them in conjunction with the Task File for the chapter on pages 148-52. In doing the tasks, some of the issues will become clearer, some of the contrasts will becomes starker.

We will start by looking at a number of‘Grammar’ issues.

| Sentence constructions |

Complements: a complement is used with verbs like ‘be’, ‘seem’, ‘look’ etc. to give information about the subject. For example, the sentence ‘She seems happy’ contains a subject (‘She’), a verb (‘seems’) and a complement (‘happy’). Examples of other sentences with complements are ‘They are Irish’, ‘He was a brilliant pianist’, ‘She was in a bad mood’.

Subject + verb only: some sentences are formed with only subjects and verbs (e.g. ‘He laughed’, ‘They disagreed’, ‘It poured!’). Verbs such as these which can’t take an object are called intransitive, e.g. ‘laugh’, ‘disagree’. Some verbs can be either transitive or intransitive, e.g. ‘She opened the door/The door opened’.

Two objects: there are two kinds of objects, direct and indirect. Direct objects refer to things or persons affected by the verb, e.g. ‘He sang a song’. ‘Pizarro conquered Peru’, ‘She loved him’.

An indirect object refers to the person or thing that (in one grammarian’s phrase) ‘benefits’ from the action, e.g. ‘He sang me a song’, ‘She painted him a picture, ‘I gave a ring to my girlfriend’. ‘Why should we pay taxes to the government?’.

Adverbial (phrases): adverbials or adverbial phrases complement the verb in the same way that a complement ‘complements’ the subject, e.g. ‘He lived in Paris’ (adverbial of place), ‘They arrived late/at night’ (adverbial of

time), ‘She sings beautifullv/like an angel’ (adverbial of manner).

Multi-clause sentences: all the sentences we have looked at so far are simple sentences, that is, they only have one clause. We can make much longer and more complex sentences by joining and amalgamating a number of different clauses. For example, the following sentences:

‘The girl met the woman.’

‘The woman was standing by the canal.’

‘They went to a café.’

‘They had a meal.’

‘They enjoyed it very much.’ can be amalgamated into a multi-clause sentence like this:

‘The girl met the woman who was standing by the canal and they went to a café and had a meal, which they enjoyed very much.’

It is possible also to convert some elements of the separate sentences into phrases, e.g. ‘The girl met the woman standing by the canal...’ etc.

| Parts of speech |

The parts of speech which teachers must be able to recognise are summarised in the chart on page 37.

We can now look at each of these parts of speech in more detail.

| Noun types |

Many words are sometimes countable when they mean one thing but uncountable when they mean something different. For example, the word ‘sugar’ is uncountable when we say ‘I like sugar’, ‘I’d like some sugar’, but countable if we say ‘One sugar or two?’ (where ‘sugar’ = spoonful/cube of sugar). When we talk about someone’s hair, it is an uncountable noun (we don’t say ‘He’s going bald, he hasn’t got many hairs’ - instead, we say ‘He hasn’t got much hair’), but we can talk about ‘a hair’ or ‘the hairs on his neck’ in which case the word (which has a different meaning) is countable.

Plural nouns, singular verbs: there are some nouns that appear to be plural, but which behave as if they are singular - you can only use them with singular verbs, e.g. ‘Darts is a popular pub game’, ‘The news is depressing’.

| part of speech | description | examples (words) | examples (sentences etc.) |

| noun (noun phrase) | a word (or group of words) that is the name of a person, a place, a thing or activity or a quality or idea; nouns can be used as the subject or object of a verb | Eleanor Devon book sense walking stick town hall | Eleanor arrives tomorrow. 1 love Devon. 1 recommend this book. Use your common sense. 1 don't need a walking stick. Meet me at the town hall. |

| pronoun | a word that is used in place of a noun or noun phrase | her she him they | Jane's husband loves her. She met him two years ago. Look at him! They don't talk much. |

| adjective | a word that gives more information about a noun or pronoun | kind better impetuous best | What a kind man! We all want a better life! She's so impetuous. That's the best thing about her. |

| verb | a word (or group of words) which is used in describing an action, experience or state | write ride be set out | He wrote a poem. 1 like riding horses. We are not amused. She set out on her journey. |

| adverb (adverbial phrase) | a word (or group of words) that describes or adds to the meaning of a verb, adjective, another adverb or a whole sentence | sensibly carefully at home in half an hour | Please talk sensibly. He walked across the bridge carefully. 1 like listening to music at home. See you in half an hour. |

| preposition (prepositional phrase) | a word (or group of words) which is used to show the way in which other words are connected | for of in on top of | a plan for life Bring me two bottles of wine. Put that in the box. You'll find it on top of the cupboard. |

| determiner | definite article indefinite article possessives demonstratives quantifiers | the a an my, your etc. this, that, these, those some,many, few etc. | the queen of hearts a princess in love an article in the paper my secret life Look at those photographs! Few people believed him. |

| conjunction | a word that connects sentences, phrases or clauses | and so but | fish and chips My car broke down, so 1 went by bus. 1 like it but 1 can't afford it. |

examples (See Countable and uncountable nouns on page 36.) The weather is terrible today, (uncountable)

There isn't much doubt about the future, (uncountable)

He hasn't got much money, (uncountable)

There aren't many people out in this storm, (countable)

She's got a lot of friends to help her through this, (countable) I've only got a few coins in my pocket, (countable)

Collective nouns: nouns which describe groups or organisations (e.g. ‘family’, ‘team’, ‘government’) are called collective nouns. They can either be singular or plural depending on whether we are describing the unit or its members. We can say ‘The army are advancing’ or ‘The army is advancing’. This choice isn’t usually available in American English, however, where you would expect speakers to use singular verbs only.

Date: 2015-02-16; view: 5261

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| How to Teach English 3 page | | | How to Teach English 5 page |