CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Love begins, or should begin, at home. For me that means Sam and Grace, Dad and Mom, who have loved me for more than fifty years. Without them I would still be seeking love instead of writing about it. Home also means Karolyn, to whom I have been married for more than forty years. If all wives loved as she does, fewer men would be looking over the fence. Shelley and Derek are now out of the nest, exploring new worlds, but I feel secure in the warmth of their love. I am blessed and grateful.

I am indebted to a host of professionals who have influenced my concepts of love. Among them are psychiatrists Ross Campbell, Judson Swihart, and Scott Peck. For editorial assistance, I am indebted to Debbie Barr and Cathy Peterson. The technical expertise of Tricia Kube and Don Schmidt made it possible to meet publication deadlines. Last, and most important, I want to express my gratitude to the hundreds of couples who, over the past thirty years, have shared the intimate side of their lives with me. This book is a tribute to their honesty.

chapter one

WHAT HAPPENS TO LOVE AFTER THE WEDDING?

At 30,000 feet, somewhere between Buffalo and Dallas, he put his magazine in his seat pocket, turned in my direction, and asked, “What kind of work do you do?”

“I do marriage counseling and lead marriage enrichment seminars,” I said matter-of-factly.

“I’ve been wanting to ask someone this for a long time,” he said. “What happens to the love after you get married?”

Relinquishing my hopes of getting a nap, I asked, “What do you mean?”

“Well,” he said, “I’ve been married three times, and each time, it was wonderful before we got married, but somehow after the wedding it all fell apart. All the love I thought I had for her and the love she seemed to have for me evaporated. I am a fairly intelligent person. I operate a successful business, but I don’t understand it.”

“How long were you married?” I asked.

“The first one lasted about ten years. The second time, we were married three years, and the last one, almost six years.”

“Did your love evaporate immediately after the wedding, or was it a gradual loss?” I inquired.

“Well, the second one went wrong from the very beginning. I don’t know what happened. I really thought we loved each other, but the honeymoon was a disaster, and we never recovered. We only dated six months. It was a whirlwind romance. It was really exciting! But after the marriage, it was a battle from the beginning.

“In my first marriage, we had three or four good years before the baby came. After the baby was born, I felt like she gave her attention to the baby and I no longer mattered. It was as if her one goal in life was to have a baby, and after the baby, she no longer needed me.”

“Did you tell her that?” I asked.

“Oh, yes, I told her. She said I was crazy. She said I did not understand the stress of being a twenty-four-hour nurse. She said I should be more understanding and help her more. I really tried, but it didn’t seem to make any difference. After that, we just grew further apart. After a while, there was no love left, just deadness. Both of us agreed that the marriage was over.

“My last marriage? I really thought that one would be different. I had been divorced for three years. We dated each other for two years. I really thought we knew what we were doing, and I thought that perhaps for the first time I really knew what it meant to love someone. I genuinely felt that she loved me.

“After the wedding, I don’t think I changed. I continued to express love to her as I had before marriage. I told her how beautiful she was. I told her how much I loved her. I told her how proud I was to be her husband. But a few months after marriage, she started complaining; about petty things at first—like my not taking the garbage out or not hanging up my clothes. Later, she went to attacking my character, telling me she didn’t feel she could trust me, accusing me of not being faithful to her. She became a totally negative person. Before marriage, she was never negative. She was one of the most positive people I have ever met. That is one of the things that attracted me to her. She never complained about anything. Everything I did was wonderful, but once we were married, it seemed I could do nothing right. I honestly don’t know what happened. Eventually, I lost my love for her and began to resent her. She obviously had no love for me. We agreed there was no benefit to our living together any longer, so we split.

“That was a year ago. So my question is, What happens to love after the wedding? Is my experience common? Is that why we have so many divorces in our country? I can’t believe that it happened to me three times. And those who don’t divorce, do they learn to live with the emptiness, or does love really stay alive in some marriages? If so, how?”

The questions my friend seated in 5A was asking are the questions that thousands of married and divorced persons are asking today. Some are asking friends, some are asking counselors and clergy, and some are asking themselves. Sometimes the answers are couched in psychological research jargon that is almost incomprehensible. Sometimes they are couched in humor and folklore. Most of the jokes and pithy sayings contain some truth, but they are like offering an aspirin to a person with cancer.

The desire for romantic love in marriage is deeply rooted in our psychological makeup. Almost every popular magazine has at least one article each issue on keeping love alive in a marriage. Books abound on the subject. Television and radio talk shows deal with it. Keeping love alive in our marriages is serious business.

With all the books, magazines, and practical help available, why is it that so few couples seem to have found the secret to keeping love alive after the wedding? Why is it that a couple can attend a communication workshop, hear wonderful ideas on how to enhance communication, return home, and find themselves totally unable to implement the communication patterns demonstrated? How is it that we read a magazine article on “101 Ways to Express Love to Your Spouse,” select two or three ways that seem especially good to us, try them, and our spouse doesn’t even acknowledge our effort? We give up on the other 98 ways and go back to life as usual.

We must be willing to learn our spouse’s primary love language if we are to be effective communicators of love.

The answer to those questions is the purpose of this book. It is not that the books and articles already published are not helpful. The problem is that we have overlooked one fundamental truth: People speak different love languages.

In the area of linguistics, there are major language groups: Japanese, Chinese, Spanish, English, Portuguese, Greek, German, French, and so on. Most of us grow up learning the language of our parents and siblings, which becomes our primary or native tongue. Later, we may learn additional languages but usually with much more effort. These become our secondary languages. We speak and understand best our native language. We feel most comfortable speaking that language. The more we use a secondary language, the more comfortable we become conversing in it. If we speak only our primary language and encounter someone else who speaks only his or her primary language, which is different from ours, our communication will be limited. We must rely on pointing, grunting, drawing pictures, or acting out our ideas. We can communicate, but it is awkward. Language differences are part and parcel of human culture. If we are to communicate effectively across cultural lines, we must learn the language of those with whom we wish to communicate.

In the area of love, it is similar. Your emotional love language and the language of your spouse may be as different as Chinese from English. No matter how hard you try to express love in English, if your spouse understands only Chinese, you will never understand how to love each other. My friend on the plane was speaking the language of “Affirming Words” to his third wife when he said, “I told her how beautiful she was. I told her I loved her. I told her how proud I was to be her husband.” He was speaking love, and he was sincere, but she did not understand his language. Perhaps she was looking for love in his behavior and didn’t see it. Being sincere is not enough. We must be willing to learn our spouse’s primary love language if we are to be effective communicators of love.

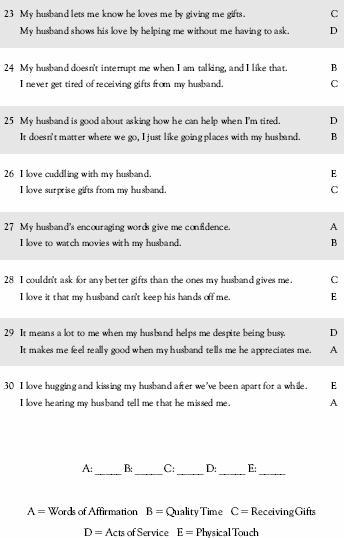

My conclusion after thirty years of marriage counseling is that there are basically five emotional love languages—five ways that people speak and understand emotional love. In the field of linguistics a language may have numerous dialects or variations. Similarly, within the five basic emotional love languages, there are many dialects. That accounts for the magazine articles titled “10 Ways to Let Your Spouse Know You Love Her,” “20 Ways to Keep Your Man at Home,” or “365 Expressions of Marital Love.” There are not 10, 20, or 365 basic love languages. In my opinion, there are only five. However, there may be numerous dialects. The number of ways to express love within a love language is limited only by one’s imagination. The important thing is to speak the love language of your spouse.

We have long known that in early childhood development each child develops unique emotional patterns. Some children, for example, develop a pattern of low self-esteem whereas others have healthy self-esteem. Some develop emotional patterns of insecurity whereas others grow up feeling secure. Some children grow up feeling loved, wanted, and appreciated, yet others grow up feeling unloved, unwanted, and unappreciated.

The children who feel loved by their parents and peers will develop a primary emotional love language based on their unique psychological makeup and the way their parents and other significant persons expressed love to them. They will speak and understand one primary love language. They may later learn a secondary love language, but they will always feel most comfortable with their primary language. Children who do not feel loved by their parents and peers will also develop a primary love language. However, it will be somewhat distorted in much the same way as some children may learn poor grammar and have an underdeveloped vocabulary. That poor programming does not mean they cannot become good communicators. But it does mean they will have to work at it more diligently than those who had a more positive model. Likewise, children who grow up with an underdeveloped sense of emotional love can also come to feel loved and to communicate love, but they will have to work at it more diligently than those who grew up in a healthy, loving atmosphere.

Seldom do a husband and wife have the same primary emotional love language. We tend to speak our primary love language, and we become confused when our spouse does not understand what we are communicating. We are expressing our love, but the message does not come through because we are speaking what, to them, is a foreign language. Therein lies the fundamental problem, and it is the purpose of this book to offer a solution. That is why I dare to write another book on love. Once we discover the five basic love languages and understand our own primary love language, as well as the primary love language of our spouse, we will then have the needed information to apply the ideas in the books and articles.

Once you identify and learn to speak your spouse’s primary love language, I believe that you will have discovered the key to a long-lasting, loving marriage. Love need not evaporate after the wedding, but in order to keep it alive most of us will have to put forth the effort to learn a secondary love language. We cannot rely on our native tongue if our spouse does not understand it. If we want him/her to feel the love we are trying to communicate, we must express it in his or her primary love language.

chapter two

Date: 2015-02-03; view: 1206

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Holiday in London | | | KEEPING THE LOVE TANK FULL |