CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

TO NORMAN SHERRY

March 20, 1991

Dear Norman,

I have been thinking over again your letter of queries. I think you should pay more attention to the background of the war at that point. The importance of Freetown was this. The Mediterranean was completely closed and all convoys military or otherwise had to go to Egypt and North Africa via the Atlantic and the West Coast, and Freetown was the main port of call. After de Gaulle had attacked Dakar unsuccessfully we were militarily at war with Vichy France and Freetown was more than half bordered by French Guinea in Vichy hands. We had to be prepared at any time for a military assault. I had to have agents near the border on the look out for any possible movements by the French. I imagine this was why I was travelling a number of times in the interior to find agents and to check with them.

My final quarrel with the man in Lagos was when he refused permission for me to go up to the border of French Guinea where I had made an appointment with the English Commissioner because a Portuguese boat was arriving at the same time in Freetown. The search was perfectly competently done by the police and didn’t need me, but I had to cancel my appointment with the Commissioner which angered him and caused trouble. The quarrel reached a point where Lagos cut me off my pay which used to come by diplomatic bag. I had to borrow money from the Commissioner of Police who luckily became a great friend, although it must have been embarrassing for him.52NS 2: 117 and Shelden, 294, identify this man as Captain Brodie. Because of my cover all my telegrams came in to the police station in a code unknown to the police and I had to send all my telegrams out from the police station in a code unknown to them. Anyway this was the end of my relations with Lagos and I was allowed in future to deal direct with London.

[—]

‘All I do is go from one room to another,’ said Graham Greene on 12 February 1991. His health continued to decline and, exhausted, he entered Providence Hospital in Vevey, where Yvonne Cloetta and Caroline Bourget were in constant attendance. On 2 April he received the last sacraments from Father Durán, who was following an arrangement for his death made years earlier. On 3 April at 11.40 a.m. he died. He was buried in the village cemetery at Corseaux. Of his life’s work, he remarked to Martine Cloetta on 1 April, ‘A few, yes, are good books. Perhaps people will think of me from time to time as they think of Flaubert.’

1 Mikhail Gorbachev had taken over as Secretary General of the Communist Party on 11 March 1985. His first summit with Ronald Reagan was set for November.

2 Christopher Hawtree’s edition of the magazine Night and Day had recently appeared with a preface by Greene.

3 Ronald Reagan had a portion of his colon removed on 13 July 1985.

4 Greene arrived in Panama on 30 November.

5 See Alberto Huerta, ‘El lugar de Don Quijote: Miguel de Unamuno, Graham Greene y Carlos Fuentes’, in Religion y Cultura (Julio–Agosto 1986).

6 Congratulating him on being awarded the Order of Merit.

7 She had been one of a number of friends who attempted to support Raymond Chandler in times of depression. (Obituary of Rickards, Guardian, 14 July 2005)

8 J. B. Priestley received his OM in 1977.

9 They made love in a first-class carriage. See obituary of Jocelyn Rickards, Telegraph (12 July 2005).

10 A cover endorsement for The Painted Banquet, published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson in 1987.

11 Durán, 268–9; ODNB.

12 James Greene is himself a distinguished poet and translator. See Woman, Child, Alphabet (forthcoming) and other works already in print.

13 Julia Camoys Stonor’s brother, the 7th Lord Camoys.

14 The playwright and memoirist John Mortimer (b. 1923) is a leading barrister.

15 He was, in fact, held at Ravensbrück concentration camp and shot in Berlin (see p. 59).

16 The text is now available in Reflections, 316–17.

17 A Georgian restaurant in Moscow; it is referred to in The Human Factor, 248.

18 Sir Basil Zaharoff (1849–1936), the director and chairman of the munitions firm Vickers-Armstrong during World War I. He is very likely the model for Sir Marcus in A Gun For Sale (see Mockler, 118).

19 In a letter to The Times (15 September 1980) Greene referred to the Prime Minister as ‘Zaharoff-Thatcher’ over the sale of arms to the Pinochet regime in Chile. See Yours etc., 196–8.

20A Far Cry from Kensington.

21 Greene’s dislike for his own books is not to be taken seriously. The Captain and the Enemy, though on a smaller scale than the great works of his mid-career, may be an unnoticed masterpiece. It is at the very least a scouring of the rag and bone shop of the heart, bringing together with absolute narrative precision, material from his schooldays, his six-month truancy with the Richmonds and his sojourns in Panama. The opening paragraph about a boy won in a game of backgammon is certainly one of the most memorable in modern fiction.

22 They met again in early May 1989.

23 See Burgess’s obituary in the Daily Telegraph reprinted as ‘Graham Greene: A Reminiscence’ in One Man’s Chorus, ed. Ben Forkner (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1998), 252–6.

24 E-mail to RG, 3 March 2006. See ‘Our Man in Tallinn’, Articles of Faith, 165–79.

25 Graham’s friend, the Norwegian poet Nordahl Grieg.

26 An obvious error, Greene writes ‘days’.

27 See A. J. Ayer, ‘What I Saw when I was Dead’, National Review (14 October 1988); NS 3: 793; Cloetta, 186–7; and p. 367 of this volume.

28 David Footman was an MI6 officer, a friend of Maclean’s, and the author of various works on the Soviet Union. See Cecil’s A Divided Life: A Biography of Donald Maclean (London: The Bodley Head, 1988), 146.

29 See A Divided Life, 138 and 167.

30 Greene signed several petitions protesting against the fatwa.

31 Durán.

32 See Anthony Mockler, Graham Greene: Three Lives (1994). After seeing extracts in the Sunday Telegraph, Greene refused Mockler permission to quote from his works.

33 Professor Küng has no recollection of which essay he sent to Greene.

34 John Wilkins was the editor of The Tablet 1982–2004.

35 Burns, who had been involved with the ownership of the magazine since the 1930s, had taken over as editor from Douglas Woodruff in 1967.

36 See Ian Ker, John Henry Newman: A Biography (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988), 652–84.

37 Daniel and Sinyavsky (see p. 291).

38 French investigative journalist.

39 Greene’s final illness was a form of leukaemia.

40 John Cornwell, ‘Why I am Still a Catholic: Graham Greene on God, Sex and Death‘, Articles of Faith, 131.

41 See NYRB 2 Dec. 2004 and 10 Feb. 2005.

42 Marchese Bernardo Patrizi, a member of the papal nobility with an estate at Gerneto near Monza. The ‘meeting’ with Padre Pio took place at San Giovanni Rotondo near Foggia in southern Italy.

43 Catherine Walston.

44 For more on Padre Pio, see Allain, 156–7.

45 On p. 206 Graham refers to his audience with Pius XII occurring in 1950. The fiftieth anniversary of the Pope’s ordination to the priesthood occurred on 2 April 1949.

46 Woodward notes: ‘the only section of proofs where a whole page was missing was the chapter entitled “Sanctity and Sexuality.” For all his interest in Padre Pio, I like to think that is the chapter Greene turned to first.’

47 Shirley Temple was appointed ambassador to Prague by the elder George Bush. Far removed from the libel case of 1938 (see p. 83), she had struck up a late friendship with the novelist.

48 Amanda Saunders.

49 Greene had long believed in J. W. Dunne’s theory, expounded in An Experiment with Time (1927), that dreams could provide glimpses of the future. Greene also absorbed Dunne’s fascination with ‘serial’ dreams.

50 Despite the mollifying tone, Greene’s position is unchanged from p. 411.

51 Ben Greene, one of the ‘rich Greenes’ of Berkhamsted, was held under this wartime regulation that allowed the Home Secretary to have anyone of hostile origin or association detained (Shelden, 20). Jeremy Lewis, who is writing a book about the whole Greene family, will present further information about Ben Greene’s incarceration.

52 Durán, 91 and 340; Cloetta, 188.

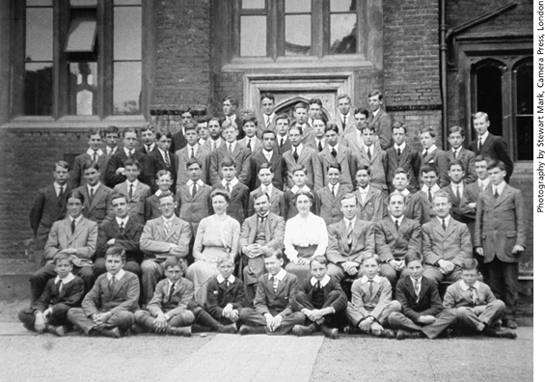

Berkhamsted School, 1914. Graham sits at the centre of the front row. His father Charles Greene, who was headmaster, sits directly behind him.

Lady Ottoline Morrell was an early supporter of Graham Greene’s work. In this photograph from 1930 she stands on the left. Beside her are Vivien Greene, holding a dog, Graham, and the critic and journalist Basil de Sélincourt.

‘— think of us as moral lepers.’ (this page) Edith Sitwell shrewdly spotted Graham Greene as a rising talent in the mid-1920s and remained a close friend for forty years.

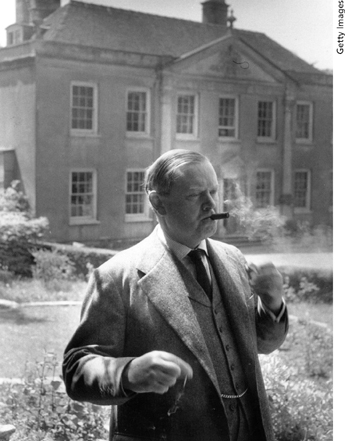

Lighting up a stinker at ‘Stinkers’, Evelyn Waugh stands in front of his house, Piers Court in Stinchcombe, Gloucestershire.

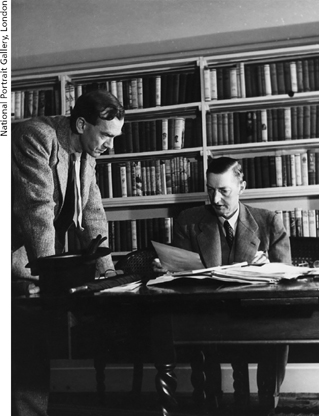

Graham Greene as publisher with Eyre & Spottiswoode in 1947. Seated is the managing director Douglas Jerrold. Greene soon resigned after a row with the novelist Anthony Powell.

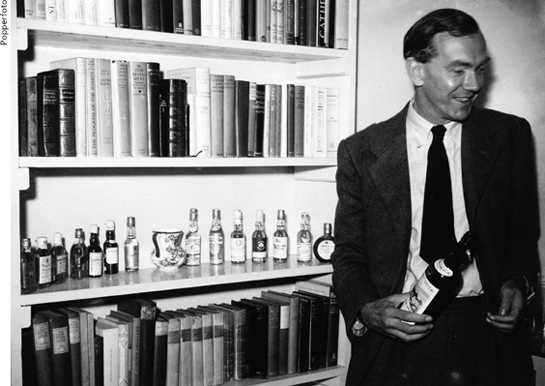

Graham uncorked. Note the miniature bottles in the background. A similar collection figures in Our Man in Havana.

The Swedish actress Anita Björk, with whom Graham had a loveaffair in the late 1950s. Here she sits beside Gregory Peck in a still from Night People (1954).

Graham Greene and Jocelyn Rickards (front right) had a brief affair in c. 1953. Here they are with friends at Battersea Funfair.

Graham on a picnic in Switzerland with his grandsons Andrew and Jonathan Bourget.

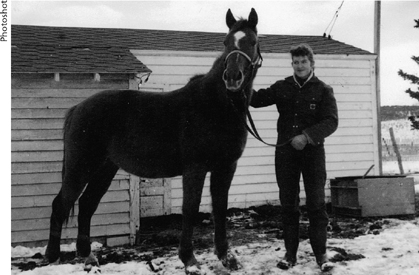

‘It makes one feel there’s some point in writing books after all.’ (this page) Graham helped his daughter Caroline to buy a ranch in Alberta, Canada. Here she stands with her horse Silence, the model for Seraphina in Our Man in Havana.

‘I can stir up a little trouble if necessary!’ (this page) Graham trying to slip over the American border from Canada, c. 1955.

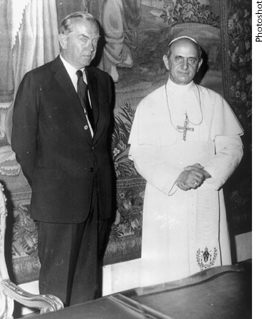

‘— a horrible photo of me and the Pope.’ (this page) Graham Greene at the Vatican with Pope Paul VI in 1966.

‘— he always carried a revolver in his pocket!’ (this page) A poet and a member of General Omar Torrijos’s security guard, Chuchu took Graham to see whatever he wanted in Panama, including the canal and a haunted house.

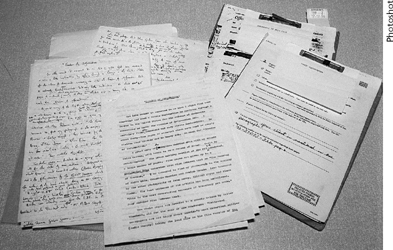

FBI file on Graham Greene offered for sale at Sotheby’s. Oddly enough, the file contained almost nothing he had not made public himself.

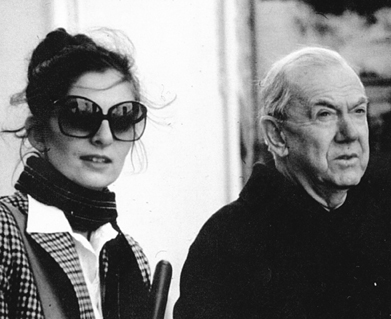

‘I have absolute trust in you …’ (this page) Graham and his niece Louise Dennys. She edited his last works and was his Canadian publisher.

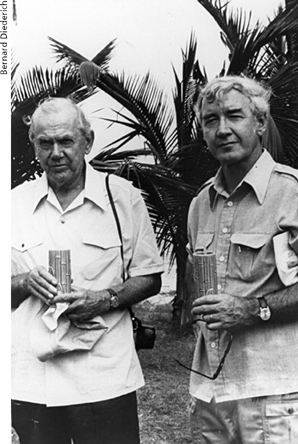

‘I doubt if the C.I.A. will enjoy having me around!’ (this page) Graham’s travels in Central America were guided by Time correspondent Bernard Diederich. Here they are sipping rum punch on the Panamanian island of Contadora.

‘You have reached the point when all the little people become jealous.’ (this page) Greene thought Dame Muriel Spark one of the few brilliant novelists of his time.

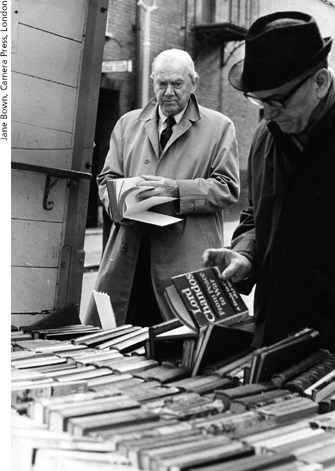

Hunting for bargains. Greene believed that if he had not been a novelist he might have been a bookseller.

The burial of Graham Greene in Corseaux, Switzerland, in 1991. In the background are, from left, his estranged wife Vivien Greene, daughter Caroline Bourget and companion Yvonne Cloetta.

Abbreviations

| Adamson | Judith Adamson, Graham Greene and Cinema (Norman, OK: Pilgrim Books, 1984) |

| Allain | Marie-Françoise Allain, The Other Man: Conversations with Graham Greene, trans. Guido Waldman (London: The Bodley Head, 1983) |

| Amory | Mark Amory, ed., The Letters of Evelyn Waugh (London: George Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1980) Articles of Faith Ian Thomson, ed., Articles of Faith: The Collected Tablet Journalism of Graham Greene (Oxford: Signal Books, 2006) |

| Cash | William Cash, The Third Woman (London: Little, Brown, 2000) |

| Cloetta | Yvonne Cloetta and Marie-Françoise Allain, In Search of a Beginning: My Life with Graham Greene, trans. Euan Cameron (London: Bloomsbury, 2004) |

| Diederich and Burt | Bernard Diederich and Al Burt, Papa Doc: Haiti and its Dictator (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972) |

| Durán | Leopoldo Durán, Graham Greene: Friend and Brother, trans. Euan Cameron (London: Harper Collins, 1994) |

| Falk | Quentin Falk, Travels in Greeneland: The Cinema of Graham Greene (London: Quartet Books, 1984) |

| Hazzard | Shirley Hazzard, Greene on Capri: A Memoir (London: Virago, 2000) |

| Mockler | Anthony Mockler, Graham Greene: Three Lives (Angus: Hunter Mackay, 1994) |

| NS | Norman Sherry, The Life of Graham Greene, 3 vols (London: Jonathan Cape, 1989–2004) |

| ODNB | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography RKN R. K. Narayan, My Days (1973; London: Picador, 2001) |

| Shelden | Michael Shelden, Graham Greene: The Man Within (London: William Heinemann, 1994) |

| St John | John St John, William Heinemann: A Century of Publishing, 1890–1990 (London: William Heinemann, 1990) |

| Tracey | Michael Tracey, A Variety of Lives: A Biography of Sir Hugh Greene (London: The Bodley Head, 1983) |

| Waugh | Michael Davie, ed., The Diaries of Evelyn Waugh (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1976) |

| West | W. J. West, The Quest for Graham Greene (London : Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1997) |

| Yours etc. | Christopher Hawtree, ed., Yours etc.: Letters to the Press (London and New York: Reinhardt in Association with Viking, 1989) |

Acknowledgements and Sources

I am grateful, above all, to Francis Greene and Caroline Bourget, who encouraged me to undertake this work and then patiently answered literally thousands of my queries over a period of five years. I note with great sadness the passing of Amanda Saunders (née Dennys), who was involved in every stage of the preparation of this book apart from its appearance. As Graham Greene’s secretary, she was very close to her uncle while he lived and then devoted an enormous effort to the affairs of his literary estate, sacrificing time that she might have given to her own work as a photographer and painter. Her sister Louise Dennys of Knopf Canada has devoted a great effort to this project in the very painful time of her sister’s illness and death.

I have likewise enjoyed the extraordinary kindness and good counsel of other members of Graham Greene’s family including Nicholas Dennys, James Greene, Oliver Greene and Rupert Graf Strachwitz. I would like to make special note of my debt to two of Graham Greene’s surviving close friends, Bernard Diederich and Professeur Michel Lechat, who lavished their time on my concerns. Bruce Hunter of David Higham Associates has advised me and watched out for my interests over a period of almost twenty years. Richard Beswick of Little, Brown has exercised great patience with a slow author and keen insight over his manuscript.

The list of people who lent their time and assistance to this project is long and my sense of obligation to them is great: Judith Adamson, Nobuko Albery, Marie Françoise Allain, Christopher Andrew, Verity Andrews, John Atteberry, John Baird, Lisa Bankoff, Shelley Barber, Jill Bialosky, Andrew Biswell, Anita Björk, Mike Bott, Carol Bowie, Bill Burns, Euan Cameron, Priscilla Chadwick, Greg Chamberlain, Giles Clark, Chérie Collins, Rowan Cope, Jan Culik, Barry Day, Hugo de Quehen, Kildare Dobbs, Linda Dobbs, Mitch Douglas, Richard Eder, Jarmila Emmerova, Patrice Fox, Miranda France, Frederick Franck, Alan Friedman, Paul Goring, Deirdre Greene, Dustin Griffin, Peter Grogan, Molly O’Hagan Hardy, Selina Hastings, Christopher Hawtree, James Hodkinson SJ, Alberto Huerta, Ian Hunter, Dom Philip Jebb, Pierre Joannon, the late Aubelin Jolicoeur, David Knight, James Knox, Michael Korda, Hans Küng, Jørgen Leth, Jeremy Lewis, Harold Love, Iain Antony Macleod, John Maddicott, Diane Martin, Lucy McCann, Michael Mewshaw, Michael Millman, Janet Moat, Anthony Mockler, Gilles Mongeau SJ, the late John Muggeridge, Karl Orend, David Pearce, Rolando Pieraccini, Joan Reinhardt, Timothy Rogers, Jean Rose, Hilary Rost, Nicholas Scheetz, Ken Sherwood, Rosemary Shipton, the late Francis Sitwell, Josef Skvorecky, Sam Solecki, Thomas Staley, Hon. Mrs Julia Camoys Stonor, Nicholas and Margaret Swarbrick, Ian Thomson, Robert Vilain, James Watson, Alexander Waugh, Lady Teresa Waugh, Tara Wenger, Peter Winnington and Ralph Wright OSB.

I am for ever in the debt of my wife, Marianne Marusic, and my children Sarah and Samuel Greene for their constant encouragement and their forbearance.

Date: 2015-02-03; view: 6544

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| TO NORMAN SHERRY | | | OWNERS OF LETTERS |