CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

The swooning economy is in desperate need of investment

NINA KULIKOVA hid in her bathtub and cried when the war neared her home this summer in Sloviansk, a city in eastern Ukraine. A shell hit a neighbouring stairwell, shattering her windows and punching a crater in the middle of her apartment block. No one has come to rebuild 4 Bulvarnaya Street. Ms Kulikova has nowhere to go. Meanwhile, the prices of food, medicine and utilities have all spiked. Her husband collects bottles and cartons for recycling to make ends meet.

√од революции и войны зан€ла мрачное сказываетс€ на экономике ”краины. ¬¬ѕ может упасть на 10% в этом году. ¬алюта, гривна, погрузилс€ почти 50% по отношению к доллару в 2014 году инфл€ци€ ударил 19%; ¬ начале этого года, цены были стабильными. ÷ентральный банк повысил ставки на этой неделе, в третий раз в этом году, до 14%. ѕотребительские расходы во втором квартале вырос на 5% по сравнению с предыдущим годом, но это, веро€тно, отражает ажиотажного спроса; это, веро€тно, спад в ближайшее врем€ тоже.

In April the IMF co-ordinated a bail-out to which it pledged to contribute $17 billion over two years. A coalition of Western countries provided smaller amounts. So far about $7 billion has been dispersed. But Ukraine needs more than temporary financing, and the conditions attached may be exacerbating its woes.

UkraineТs economic problems have been long in the making. Two decades of stalled reforms and rapacious leadership have left the average Ukrainian about 20% poorer than she was when the Soviet Union collapsed. Ill-planned privatisations in the 1990s spawned an oligarchic class that sucked up most of the countryТs wealth for itself. Corruption is a way of life. University students bribe their professors to get a good grade; taxmen reckon the majority of businesses pay their workers at least partly in cash to evade tax. Transparency International, an advocacy group, puts Ukraine 144th out of 177 countries in a global ranking of public perceptions of corruption.

The war in the provinces of Donetsk and Luhansk, the countryТs industrial powerhouse, has compounded these failings. The two normally account for 16% of UkraineТs GDP, supply 95% of its coal and produce a disproportionate share of exports. In September industrial production in Luhansk fell by 85% year-on-year; in Donetsk it fell by 60%. Other parts of the country are also suffering, as imports get more expensive and credit impossible to find. Even agriculture, which many had hoped would power growth, is struggling: Macquarie, a bank, expects wheat farmers to produce 12% less next season.

On the surface, UkraineТs public finances, at least, seem reasonably sound. Public debt has risen in the past decade but it is no Greece. According to the IMF, the debt-to-GDP ratio will be around 70% by the end of the year (though this calculation includes the separatist regions). This year UkraineТs interest payments will amount to 3% of GDP, which is low by international standards.

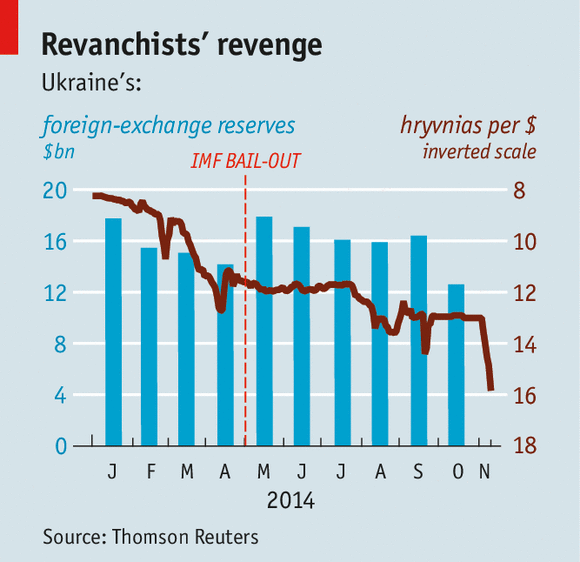

But Ukraine is running out of the money to service these debts. Few people, least of all the IMFТs technocrats, predicted that the fighting would be so fierce. As investors pull money out of Ukraine, the central bank has spent billions of dollars in a desperate attempt to prop up the tumbling hryvnia: foreign-exchange reserves are now at their lowest level in a decade. The central bankТs efforts have done little: this week alone the hryvnia fell 14% (see chart).

From now until the end of 2016 about $14 billion of debts denominated in foreign currencies are due. Ukraine must also pay $700m a month for gas imports from Russia. Its foreign-exchange reserves have probably dwindled to about $12 billion. Worse, the debts falling due may rise. A year ago Russia agreed to lend Ukraine И3 billion ($4.1 billion) via an international bond. The money came with an important condition: if UkraineТs debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds 60%, Russia can demand early repayment, which might, in turn, trigger an automatic default on UkraineТs other international bonds. Official figures due in March are expected to show the governmentТs debt well above the 60% threshold, enabling Russia to precipitate a default.

Meanwhile, in return for its support, the IMF wants an overhaul of UkraineТs economy. Western officials believe that Petro PoroshenkoТs government is serious about reform. Last monthТs parliamentary elections removed obstructive deputies. There have been other positive steps, such as forcing government ministers to declare their financial interests. The government has scrapped the most bizarre loopholes in its procurement rules, which are a massive source of corruption (including one that turned feed for circus animals into a conduit for graft).

The government is also tightening its belt. The IMF expects that spending, as a percentage of GDP, will fall by 4.8 percentage points over the next five yearsЧa similar diet to GreeceТs in 2010-14. According to Macro-Advisory, a consultancy, the jobs of 1m civil servants are Уunder reviewФ. An update of the Уsubsistence-minimumФ amount that pensioners receive has been put on hold. Domestic gas prices were raised by 56% this year in order to improve the finances of Naftogaz, the state-owned gas monopolist.

Though higher energy prices and a smaller budget deficit are necessary, the scale of todayТs spending cuts and price rises is likely to clobber demand in an economy that is already slumping. Austerity programmes also tend to lead to political unrestЧjust look at Greece. Ukraine is much poorer than the euro-zone periphery, and is filled with traumatised men returning from the front.

Ukraine will only prosper when private investors venture back in. That will require big investments in infrastructure, especially in the war-torn east of the country. The IMF cannot provide that; it deals in short-term financing. Yet other potential benefactors, including America and the EU, have been dragging their feet.

UkraineТs energy sector is crying out for investment. If the country were as energy-efficient as the EU average, it could probably avoid importing gas from Russia. Alongside higher prices for consumers, projects to improve home insulation, to replace old boilers and to fix leaky pipes would help. Investing in gas production also makes sense: Ukraine has big reserves but output has fallen by two-thirds since the 1970s. Mr Poroshenko has doubled taxes on domestic gas companiesЧa poor way to court investment. Unless he and his Western allies start focusing on measures to boost the economy, a slide into disarray and default seems inevitable.

Date: 2015-01-29; view: 1155

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| | | UNIT 2 SUBJECTS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW |