CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Enlargement of the vocabulary in the OE period.

In this period, known as Old English, the vocabulary was basically enlarged with the own material of the language. As Barber comments, from Proto-Indo-European, the Germanic languages have inherited many ways of forming new words, especially by the use of prefixes and suffixes (2009:128). However, Old English also borrowed words from other languages due to contact with different peoples. On of these sources is, of course, Latin. But only the 3 percent of the Old English word stock comes from Latin (Stockwell, 2001:32Latin was the official language of the Christian Church, and consequently, the spread of Christianity was accompanied by a new period of Latin borrowings (Şekerci, 2007:152). Some of these Latin borrowings are biscop, munuc (Barber, 2009:129) or priest, psalter (Jespersen,1972:39). However, some of the words in this way created do not exist presently as they were replaced by Latin or French words, for example powere (from prowian, 'to suffer') by martyr, from these period, there are also borrowings which designates names for division of time, for utensils, for articles of wearing apparel, and particularly in names of plants and trees and beast, real and mythological For example: paper, school or polite, radish (Stockwell, 2001:32). Although during this period there was a high contact between the two languages, there were not many Latin borrowings:

Old English did not borrow more Latin vocabulary because at that time there were no Latin-speaking nation or community in actual intercourse with the English [ ] Old English language, then, was rich in possibilities, and its speakers were fortunate enough to possess a language that might [ ] express everything that human speech can be called upon to express (Jespersen, 1972:45-46).

31. What is the origin of the Mod E plural ending ES and the genitive s.

In Modern English we have one major declension consisting of nouns that make their plural by adding -s; this comes to us from the Old English strong declension. But some nouns make plurals by adding -en (e.g. oxen), and these are descended from the weak declension; still others make plurals by changing their vowel (e.g. mice), and these are from the athematic declension.

The Modern English possessive is descended from the Old English masculine/neuter genitive.

32.Minor groups of verbs in OE(suppletive, preterite-presents, anomalous)

Minor groups of verbs in OE.

Suppletive, anomalous, preterite-present.

Several minor groups of OE verbs belong neither to strng, nor to weak verbs. Preterite-present (or past-present) is the most important of them. Originally the present tense forms of these verbs wore the past form, later they received present meaning, but preserved many formal features of the past tense (infinitive and participles).

The verbs were inflected in the present like the past tense of strong verbs.

In the past tense the pr?t-pres were inflected like weak verbs.

Among the verbs of the minor groups there were some anomalous verbs with irregular forms. (OE willan)

Two OE verbs were suppletive:

OE gan was built from a different root

beon is an ancient IE suppletive verb.

33. What new letters and digraphs denoting consonants appeared in ME?

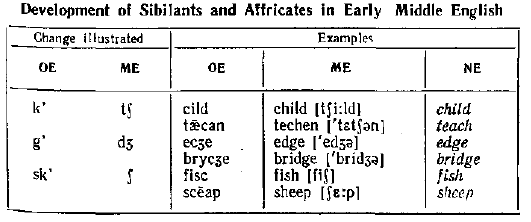

In the course of ME many new devices were introduced in the system of spelling. There were numerous graphic replacements in OE letters by new letters and digraphs. In ME runic letters passed out of use. Thorn p, and crossed d were replaced by the diagraph TH, which retained the same sound value θ and ᵹ. New sounds appeared sibilants and affricates. In early ME 3 new phonemes [tᶘ] [d ᵹ] and [ᶘ] began to be indicated by special letters and digraphs, which came into use mainly under the influence of the French scribal tradition ch, tch, g, dg, sh, ssh, sch.

34. The OE verb.

The system of the OE verb was less developed than it is now. The form building devices were gradation(vowel interchange), the use of suffixes, inflections, and suppletion. All the paradigmatic forms of the verb were synthetic. The non-finite forms of the verb in OE were the Infinitive and 2 Participles. They had categories of the finite verb but shared many features with the nominal parts of speech. 1.The infinitive had the suffix an/ian + the preposition TO. It could be used to indicate the direction or purpose of an action, and in the impersonal sentences. Participle 1 was formed by means of the suffix ende added to the stem of the infinitive: writan-writende. It was active in meaning and declined like a strong adjective. Participle 2 expressed acrions and states resulting from past acrion and was passive an meaning/ Depending on the class of the verb it was formed by vowel interchange and the suffix en (strong v) or dental suffix d/t (weak v). It was active in meaning and declined like strong adjective. The verb in OE had the following categories: Number(singular, plural, dual), Person -3, Mood imperative, indicative, subjunctive, Tense past,nonpast (present)

35.OE syntax. Types of sentences, of predicate.

The syntax of the sentances was relatively simple. Coordination of clauses prevailed over subordination. Complicated constructions werw rare. The syntactic structure of a language can be described at the level of phrase or sentence. In OE texts we find a variety of word phrases groups patterns. One of the conspicuous features of OE syntax was multiple negation. There were simple sentences compound and complex. Word order of words in OE was free. The position of word in the sentence was determined by logical and stylistic factor.

36.How did the forms of perfect tenses develop in the English language?

DEVELOPMENT OF PERFECT TENSES IN ENGLISH

The evolution of a future and perfect tense represents the most significant innovation of Modern English in comparison to earlier stages of that language. Old English had a two tense .

Crosslinguistic work (Bybee/Dahl 1989) has shown that future tense markers typically derive from:

verbs of volition

verbs of obligation

verbs of motion

During a process of grammaticalization such verbs lose specific aspects of their meaning, and thus also broadening their distribution (e. g. to human beings) and/or morphological properties: Words may, in the process of grammaticalization, also acquire semantic substance. In the development of future tense markers it is the element of prediction and intention that is newly acquired. In specific contexts (e. g. future time reference), the choice of lexical or grammatical future tense marking is obligatory (e. g. will and going to), lending support to the view that the grammaticalization in this area is advanced. The expression that has advanced furthest as a future tense marker in English is will, as it combines freely with any type of verb and aspect. The perfect is another example of the latest developments of the English tense system. Comparative linguists have identified typical historical sources of perfect markers, such as the verb have and the adverb already (K?nig 1995: 164). The English perfect has developed from originally resultative sentences with be (John is gone) and have (I have the enemy bound). Such resultative sentences express states and/or possession over states. The perfect is also used as a narrative tense, thus gradually replacing (and presumably eventually eliminating) the past tense (preterite).

All other categories of the English tense system are constituted by a combination of one of the two above-mentioned tenses with either a modal verb, or the perfect marker have. The advocates of this approach often conveniently stress the combinatorial character (K?nig 1995: 154) of these members by naming them

present perfect

past perfect

future perfect

rather than

perfect

pluperfect

future II

37.Borrowings from Latin and Greek in the period of Renaissance.

The mixed character of the English vocabulary facilitated an easy adoption of words from Latin. Many of these belong to certain derivational types. The most easily recognizable are the following:

verbs in ate, derived from the past participle of Latin verbs of the 1st conjugation in -are: aggravate, irritate, abbreviate, narrate.

verbs in ute, derived from the past participle of a group of Latin verbs of the 3rd conjugation in uere: attribute, constitute, pollute, and from the Latin deponent verb sequi with various prefixes: persecute, execute, prosecute.

verbs derived from the past participle of other Latin verbs of the 3rd conjugation: dismiss, collect, affect, correct, collapse, contradict.

verbs derived from the infinitive of Latin verbs of the 3rd conjugation: permit, admit, compel, expel, produce, also introduce, reproduce, conclude, also include, exclude.

adjectives derived from Latin present participles in ant and ent. verbs of the 2nd, 3rd, 4th conjugation: arrogant, evident, patient.

adjectives derived from the comparative degree of Latin adj. with the ior suffix: superior, junior, minor.

It is often hard or even impossible to tell whether a word was adopted into English from Latin or from French. Thus, many substantives in tion are doubtful in this respect.

38.Rise of definite and indefinite articles.

One of the directions of the development of the demonstrative pronouns se, seo, ??t led to the formation of the definite article. This development is associated with a change in form and meaning. In the manuscripts of 11&12th c. this use of the dem. pron. becomes more and more common.

In ME there arose an important formal difference between the demonstrative pronoun and the definite article: as a dem. pron., that preserved number distinctions, whereas as a def. art. usually in the weakened form it was uninflected.

The meaning and functions of the definite article became more specific when it came to be opposed to the indefinite article.

In OE there existed 2 words: an (numeral) & sum (indefinite pron.), which were often used in functions approaching those of the modern indefinite article. An was more colloquial, and sum more literary and soon lost its functions.

In early ME an lost its inflection, and in the 13th c. the uninflected oon/one and their reduced forms an/a were firmly established in all regions.

39.Development of the English vocabulary in NE.

In addition to three main sources:Greek,Latin and French(French borrowings in NE have not been assimilated and retained foreign appearance to the present day) English speakers of NE period borrowed freely from many other lang.(Italian,Dutch,Spanish,German,Russian)

Italian-words relating to art duet

Spanish-as a result of contacts with Spain in military-barricade

Russian-many technical terms came from Russian-sputnik

40.Why is English spelling different from its pronunciation?

The most conspicuous feature of Late ME texts in comparison with OE texts is the difference in spelling. The written forms in ME resemble modern forms, though the pronunciation was different.

- In ME the runic letters passed out of use. Thorn and the crossed d: đ were replaced by the digraph th-, which retained the same sound value: [Ө] & [?]; the rune wynn was displaced by double u: -w-;the ligatures ? & ? fell into disuse.

- Many innovations reveal an influence of the French scribal tradition. The digraphs ou, ie&ch were adopted as new ways of indicating the sounds [u:], [e:] & [t∫] : e.g. OE ūt, ME out [u:t]; O Fr double, ME double [duble].

- The letters j,k,v,q were first used in imitation of French manuscripts.

- The two-fold use of g- & -c- owes its origin to French: these letters usually stood for [dz] & [s] before front vowels & for [g]&[k] before back vowels: ME gentil [dzentil], mercy [mersi] & good[go:d].

- A wider use of digraphs: -sh- is introduced to indicate the new sibilant [∫]: ME ship(from OE scip); -dz- to indicate [dz]: ME edge [edze], joye [dzoiə]; the digraph wh- replaced hw-: OE hw?t, ME what [hwat].

- Long sounds were shown by double letters: ME book [bo:k]

- The introduction of the digraph gh- for [x]& [x]: ME knight [knixt] & ME he [he:].

- Some replacements were made to avoid confusion of resembling letters: o was employed to indicate u: OE munuc> ME monk; lufu> love. The letter y an equivalent og i : very, my [mi:].

41.The main historical events of ME and NE periods.

THE MIDDLE ENGLISH PERIOD

1066-1075 William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy, invades and conquers England.

English becomes the language of the lower classes (peasants and slaves). Norman French becomes the language of the court and propertied classes. Churches, monasteries gradually filled with French-speaking functionaries, who use French for record-keeping. After a while, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is no longer kept up. Authors write literature in French, not English. 1204 The English kings lose the duchy of Normandy to French kings. England is now the only home of the Norman English.

1205 First book in English appears since the conquest.

1337 Start of the Hundred Years' War between England and France.

1362 English becomes official language of the law courts. More and more authors are writing in English.

1380 Chaucer writes the Canterbury tales in Middle English. the language shows French influence in thousands of French borrowings.

1474 William Caxton brings a printing press to England from Germany. Publishes the first printed book in England. 1500-present THE MODERN ENGLISH PERIOD

1500-1650 Early Modern English period. The Great Vowel Shift gradually takes place. There is a large influx of Latin and Greek borrowings and neologisms.

1616 Shakespeare dies. Recognized even then as a genius of the English language.Wove native and borrowed words together in amazing and pleasing combinations.

1700s vocabulary (e.g. writings of Samuel Johnson).

17th-19th centuries British imperialism. Borrowings from languages around the world.

19th-20th centuries Scientific and Industrial Revolutions.Development of technical vocabularies. English has gone from an island tongue to a world language.

1945Becomes most widely studied second language, and a scientific lingua franca.

42. What is meant by the outer and inner history of a language?

The internal(inner)history of English:all the aspects of the development of language structure,i.e.,the evolution of phonology,grammar,vocabulary and writing.

The external(outer)history of English:all non-structural factors.These factors are of varied nature beginning with political(the formation of states,wars),social(changes in social structure),economic(industrialization),scientific (new inventions requiring new 'special'languages) and ending with cultural(religion,literature,introduction of printing,cultural movements).

43.After the Norman Conquest French language became very popular in England. Norman conquerors came to Britain as French speakers and bearers of French culture. Their tongue in Britain is often referred to as anglo-French or Anglo-Norman. For almost three hundred yearsFrench was the official lang. of administration: the kings court, the law courts, the church, the army and the castle. It was also everyday lang. of many nobles, of he higher clergy and of many towns-people in the South. French, alongside Latin, was the language of writing. Teaching was conducted in French. A good knowledge of French would mark a person of higher standing giving him a certain social prestige.

For all that, England never stopped being an Engish speaking country. The lower classes in the towns, and especially in the country-side, those who lived in the Midlands and North continued to speakEnglish, French was strange and hostile for them.

The struggle between French and English was bound to end in the complete victory of English. In the 13th c. only a few steps were made in hat direction. The earliest sign of the official recognition of English by the Norman kings was the famous PROCLAMATION issued by Henry III in 1258 to the councilors in Parliament. It was written in 3 languages: French, Latin and English.

44.In the Middle and NE periods the main character and directions of the evolution of unstressed vowels were the same as before: the unstressed vowels had lost many of their former distinctions their differences in quantity as well as some of their differences in quality were neutralised.In the Middle English period the pronunciation of unstressed syllables became increasingly indistinct. As compared to OE which distinguished five short vowels in unstressed position (representing three phonemes [e/i], [a] and [o/u]), ME reduced them to [e/i] or rather [ý/i], the first variant being a neutral sound. Compare: OE fiscas ME fishes [`fijýs] Fisces

The occurrence of only two vowels [i] and [ý] in unstressed final syllables is regarded as an important mark of the ME language distinguishing it on the onehand, from OE with its greater variety of unstressed vowels, and on the other hand,from the NE, when this final [ý] was altogether lost. (Compare NE risen, tale.)Some of the new unstressed vowels were not reduced to the same degree asthe OE vowels and have retained their quantitative and qualitative differences, e.g.

NE consecrate [ei], disobey [o].These examples, as well as modern polysyllabic words like alternant with[o] and [o:], direct with [ai] and [i] and others show that a variety of vowels canoccur in unstressed position, although the most frequent vowels are [i] and [ý], thelatter confined to unstressed position alone, being the result of phonetic reductionof various vowels.These development show that the gap between the set of stressed andunstressed vowels has narrowed, so that in Middle and NE we need no longerstrictly subdivide the system of vowels into two sub-systems that of stressed andunstressed vowels (as was done for OE), - even though the changes of the vowelsin the two positions were widely different and the phonetic contrast between thestressed and unstressed syllables remained very strong.

45. Development of analytical forms and new grammatical categories of verbs in OE and ME.

Since the OE period the gramatical type of the language has changed: from synthetic or inflected language into a language of the analytical type.

many changes in the verb conjugation, such as the loss of some person and number distinctions or the loss of the declension of participles,

many developments of the morphological system and the growth of new grammatical distinctions.

The number of grammatical categories grew, as did the number of categorial forms within the existing categories (e.g. a new category of aspect, or the future tense forms within the category of tense).

The changes involved the non-finite forms too, for the infinitive and the participle developed verbal features; the gerund, which arose in the Late ME period as a new type of verbal, has also developed verbal distinctions: passive and perfect forms.

46. OE written records: runic inscriptions, religious works, Anglo-Saxon chronicles.

The earliest written records of English are inscriptions on hard material made in a special alphabet known as runes. This word originally ment secret, later it was applied to the characters used in writing these inscriptions. the runes were used as letters, each symbol indicated a separate sound; each rune has its name. In some inscriptions the runes were found arranged in a fixed order making a sort of alphabet. The runic alphabet is specifically Germanic.

The number of runes in different OG languages varied from 28 to 33 in Britain against 16 or 24 on the continent.

The 2 best known runic inscriptions in England are the earliest extant OE written records: the Franks Casket and the Ruthwell Cross (both in the Northumbrian dialect).

Religious works. The most widely known secular author of Old English was King Alfred the Great (849899), who translated several books, many of them religious, from Latin into Old English. Alfred produced the following translations: Gregory the Great'sThe Pastoral Care, a manual for priests on how to conduct their duties; The Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius; and The Soliloquies of Saint Augustine.

Other important Old English translations include: Historiaeadversumpaganos by OrosiusandBede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People.

?lfric of Eynsham, wrote in the late 10th and early 11th century. He was the greatest and most prolific writer of Anglo-Saxon sermons, which were copied and adapted for use well into the 13th century. He translated the first six books of the Bible (Old English Hexateuch), and glossed and translated other parts of the Bible. The oldest collection of church sermons are the Blickling homilies in the Vercelli Book and dates from the 10th century.

OE prose is the most valuable source of information for the history of the language. The earliest samples of continuous prose are the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, brief annals of the years happenings made at various monasteries. In the 9th c they were unified at Winchester, the capital of Wessex. Though sometimes dropped or started again, they developed into a fairly complete prose history of England. Several versions of the ASC have survived.

47. Speak about the historical events which affected the development of English l.

Old English: the vocabulary is mostly West Germanic(Germanic settlement) / there are some borrowings from other languages, including Latin (through the christianization of England) and Norse (through the Viking invasions and settlements) as well as some faint traces of Celtic (from the previous rulers of the British Isles).

Middle English: the vocabulary is very heavily influenced by French, which was brought to English as the new prestige language by the Normans (the Norman conquest 1066);(the War of Roses.)1475 introduction of printing..

Middle Early Modern English: the vocabulary is very heavily influenced by Greek and Roman (think of the Renaissance, the wide spread use of the printing press to print English translations of Classical literature and by languages from around the world (think of Columbus, etc., and the discovery of plants new to English speakers that lead to the introduction of new words into English, including "coffee" and "chocolate," "muskrat" and "skunk)

50. What do we mean by the statement that 2 languages are related?

Many groups of languages are partly mutually intelligible, i.e. most speakers of one language find it relatively easy to achieve some degree of understanding in the related language(s). Often the languages are genetically related, and they are likely to be similar to each other in grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, or other features.

Linguists generally use mutual intelligibility as one of the primary factors in deciding between the two cases.

Asymmetric intelligibility is a term used by linguists to describe two languages that are considered mutually intelligible, but where one group of speakers has more difficulty understanding the other language than vice versa. There can be various reasons for this. If, for example, one language is related to another but has simplified its grammar, the speakers of the original language may understand the simplified language, but not vice versa. For example, Dutch speakers tend to find it much easier to understand Afrikaans than vice versa as a result of Afrikaans's simplified grammar.

In other cases, two languages have very similar written forms, but are pronounced very differently. If the spoken form of one of the languages is more similar to the common written form, speakers of the other language may understand this language more than vice versa. This may account for the common claim that Portuguese speakers can understand Spanish more easily than the other way around.

In some cases it is hard to distinguish between mutual intelligibility and a basic knowledge of other language. Many Belarusian and Ukrainian speakers have extensive knowledge of Russian and use it as a second language or lingua franca, or even as a first language in public or at work. Thus they can easily understand Russian, whereas speakers of Russian often can understand Ukrainian and Belarusian only partially.

Date: 2015-01-29; view: 3411

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| The greatVowel Shift | | | Pre-Roman Britain |