CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Mexican Three Card Monte

WHEN the game is played in the following manner the better has no possible chance to win, and yet it

appears simpler and easier shall the other. An entirely different subterfuge is employed by the dealer. The three cards are left perfectly flat. Sometimes the four corners are turned the very least upwards, merely enough to allow one card to be slipped under the other when Lying face down on the table, but the bend is not necessary.

The dealer now shows the faces of the three cards, and slowly lays them in a row. Then he makes a pretense of confusing the company by changing their places on the table. Now in explaining the game, he shows the faces of the cards by picking up one, and with it turning over the others, by slipping it under them and tilting them over face up. Then he turns them down again in the same manner and lays down the third card. This procedure is continued until the company understands the game, and the manner of showing the cards has grown customary, as it were.

When the bet is made and the player indicates his choice the dealer at once proclaims that the player has lost, and to prove it he picks one of the other cards and with it rapidly turns over the player's card, and then the third card, and the third card proves to be the ace.

Of course the better can really select the ace every time, but he is not permitted to turn the cards himself, or touch them at all. The dealer exchanges the card he picks up for the player's card, and again exchanges that for the third card, when apparently turning them over. The exchange is absolutely impossible to note, and is made as follows:

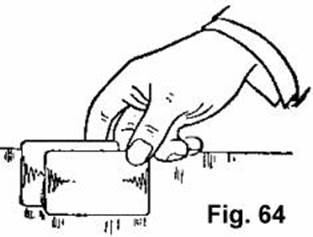

Hold the card in the right hand between the tips of thumb and first finger close to right inner end corner, thumb on top. Slide the free side of this card under the right side of the card on the table, until it is about two-thirds concealed, but half an inch exposed at the outer end. (See Fig. 63.) This will bring the upper, inner end corner of the table card, against the tip of the second finger. Now shift the thumb to the corner of the table card, holding it against the second finger, carrying it to the left and turning over the lower card with the tip of the first finger. (See Fig. 64.)

Of course there is no hesitation in the action.

The slipping of the

hand card under the table card, and the turning over of the hand card, is done with one movement. The table card is not shown at this stage, but is slipped under the third card and the exchange is again made in like manner. Then the last card is shown.

This method of exchanging can be worked with the first method of dealing or throwing, but in such case the cards are not crimped.

To perform this feat perfectly a cloth covered table must be used. When the table is of polished wood the cards slip about, and it is much more difficult to slip the hand card into position under the other.

Previous | Next

Previous | Next

Legerdemain

THERE is no branch of conjuring that so fully repays the amateur for his labor and study as slight-of-hand

with cards. The artist is always sure of a comprehensive and appreciative audience. There is no amusement or pastime in the civilized world so prevalent as card games, and almost everybody loves a good trick. But the special advantage in this respect is that the really clever card-handler can dispense with the endless devices and preparations that encumber the performer in other branches. He is ever prepared for the most unexpected demands upon his ability to amuse or mystify, and he can sustain his reputation with nothing but the family deck and his nimble fingers, making his exhibition all the more startling because of its known impromptu nature and simple accessories.

To the student who wishes to make the most rapid progress towards the actual performance of tricks, we suggest that he first take up the study and practice of our "System of Blind Shuffles" as taught in the first

part of this book, acquiring thorough proficiency in forming and using the "jog" and "break," which make this style of shuffle possible. . We are aware that all conjurers advise the shift or pass, as the first accomplishment, and while we do not belittle the merits of the shift when perfectly performed, we insist that all or any of the various methods of executing it, are among the most difficult feats the student will be called upon to acquire, and imposing such a task at the outset has a most discouraging effect. But so far as we can learn from the exhibitions and literature of conjurers, not one of them knows of, or at least employs or writes of, a satisfactory substitute; hence their entire dependence upon that artifice to produce certain results.

When the blind shuffles with the coincident jog and break, are thoroughly understood, the student should take up our "System of Palming," also treated in the first part, paying particular attention to the "bottom

palm," and with even a moderate degree of skill in these accomplishments he will be enabled to perform many of the best tricks that conjurers make entirely dependent on the shift.

For example, the common process for obtaining possession of a selected card when it is replaced in the deck is to insert the little finger over it, make a shift bringing the lower packet with the selected card to the top, palm it off in the right hand, and give the deck to the spectator to shuffle. Now it may be a matter of opinion, but we think it would appear quite as natural if the performer were to shuffle the deck himself, immediately when the card is replaced in the middle, then palm off and hand the deck to the spectator to shuffle. If the spectator shuffles for the purpose of concealing any knowledge of its whereabouts, the performer's shuffle may reasonably be expected to increase the impression that it is hopelessly lost, and especially because his shuffle is made without the least hesitation, turn, swing, concealment or patter, and apparently in the most natural and regular way. Then the performer's shuffle gives a tacit reason for holding the deck while the card is inserted, instead of permitting the spectator to take the deck in his own hands. Well executed, the blind shuffle brings the card to the top or bottom at will, defying the closest scrutiny to detect the manipulation. The card is then palmed while squaring up, and the deck now handed over for further shuffling.

Should the performer wish to palm off the selected card without employing a shuffle, we believe the "Diagonal Palm Shift" is easier and far more imperceptible than the shifting of the two packets and then

palming, assuming that the different processes are performed equally well. For this reason we suggest the early acquirement of the mentioned shift.

However, the enthusiast will not rest until every slight in the calendar has been perfectly mastered, so that he may be enabled to nonplus and squelch that particularly obnoxious but ever present individual, who with his smattering of the commoner slights always knows "exactly how it is done." Acquiring the art is in itself a most fascinating pastime, and the student will need no further incentive the moment the least progress is made.

The finished card-table expert will experience little or no difficulty in accomplishing the various slights that lie at the bottom of the conjurer's tricks. The principal feats have been already mastered in acquiring the blind shuffles, blind cuts, bottom deal, second deal, palming and replacing, the run, the crimp, culling, and stocking; and his trained fingers will readily accommodate themselves to any new positions or actions. But the mere ability to execute the slights by no means fits him for the stage or even a drawing-room entertainment. In this phase of card-handling, as with card-table artifice, we are of the opinion that the less the company knows about the dexterity of the performer, the better it answers his purpose. A much greater interest is taken in the tricks, and the denouement of each causes infinitely more amazement, when the entire procedure has been conducted in an ordinary manner, and quite free of ostensible cleverness at prestidigitation. If the performer cannot resist the temptation to parade his digital ability, it will mar the effect of his endeavors much less by adjuring the exhibition of such slights as palming and producing, single-hand shifts, changes, etc., until the wind up of the entertainment. But the slights should be employed only as a means to an end.

The amateur conjurer who is not naturally blessed with a "gift of the gab" should rehearse his "Patter" or monologue as carefully as his action. The simplest trick should be appropriately clothed with chicanery or plausible sophistry which apparently explains the procedure but in reality describes about the contrary of what takes place.

The principal slights employed in card tricks, that are not touched upon in the first part of this book, are known as "forcing," "changes," "transformations," and various methods of locating and producing selected cards. We shall also describe other methods of shifting and palming. We should mention that a shift is termed by the conjurer a "pass."

Previous | Next

Previous | Next

Shifts

● Single Handed Shift

● The Longitudinal Shift

● The Open Shift

● The S.W.E. Shift

● The Diagonal Palm-Shift

Date: 2016-04-22; view: 966

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Replacing Palm When Cutting | | | The Longitudinal Shift |