CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

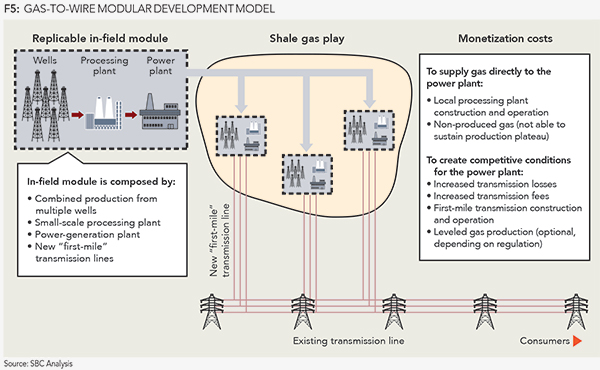

Opportunity for gas-to-wire modular developmentIn several of the 10 largest shale gas countries outside the US, electricity transmission networks are considerably more extensive and dense than gas pipeline systems. The electricity networks of China and South Africa, for example, are 10 times denser than their respective gas networks. Examples of prospective shale-gas basins that lack pipeline access but that are served by transmission lines include Paraná in Brazil, Karoo in South Africa, and Songliao in China. Some of these resources are more than 500 kilometers (about 310 miles) away from the nearest gas pipeline. Relatively extensive electricity infrastructure creates opportunities for an alternative, gas-to-wire (GTW) monetization model. This alternative model, which is being proposed in this article, is designed to develop shale-gas reserves in relatively small modules that can be systematically replicated within the field, consisting of a group of wells capable of producing at an expected plateau, connected to in-field gas processing and power generation plants, to generate electricity and send it to consumers through existing transmission lines (Figure 5).

The plant's capacity determines the size of modular reserve required - i.e. the amount of gas needed to supply the power plant over its operating life. As such, this alternative monetization model enables sustainable economic production in regions with no gas infrastructure when only a relatively small amount of gas reserves is proved, which requires a limited number of wells before final investment decision: a 100 MW combustion turbine (CT) would require, over its 20-year operating life, modular reserves of 0.15 tcf, which can be proven by an estimated 30 wells; a 500 MW natural gas combined-cycle (NGCC) power plant, meanwhile, would need 0.6 tcf, or an estimated 120 wells in order to prove reserves. Several incremental costs, or monetization costs, would need to be factored into the local gas-sale price in order to make the gas-to-wire model successful. These costs falls into two groups: (1) the incremental costs of supplying gas directly to a power plant; and (2) the incremental costs of creating competitive operating conditions for the power plant. The first group comprises: the costs of constructing and operating an in-field gas-processing plant; and the cost of non-produced gas (the portion of the reserves that will not be able to sustain the expected production plateau, due to combined well declines). The second group comprises: costs related to increased transmission losses; higher transmission fees; the construction and operation of first-mile transmission (i.e. connection between the in-field power plant and the nearest transmission line); and the incremental cost of producing gas with little variability from the expected production plateau, which will be necessary in case regulation or commercial terms impose the need for a constant supply of electricity. Date: 2015-12-11; view: 886

|