CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

UNDERUSE OF LABOR-POWER

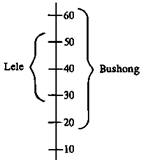

That the labor forces of primitive communities are also underused is easier to document, thanks to a greater ethnographic attention. (Besides, this dimension of primitive underproduction conforms closely to European prejudices, so that many others besides anthropologists have noticed it, although the more appropriate deduction from the cultural differences might have been that Europeans are overworked.) It is only necessary to keep in mind that the manner by which labor-power is withheld from production is not everywhere the same. The institutional modalities vary considerably: from marked cultural abbreviations of the individual working-life span to immoderate standards of relaxation—or, what is probably a better understanding of the latter, very moderate standards of "sufficient work." One of the main conclusions of Mary Douglas's brilliant comparison of Lele and Bushong economies is that in some societies people work for a much greater part of their lifetime than in others. "Everything the Lele have or do," Douglas wrote, "the Bushong have more and can do better. They produce more, live better as well as populating their region more densely than the Lele" (1962, p. 211). They produce more largely because they work more, as demonstrated along one dimension by the remarkable diagram Douglas presents of male working life span in the two societies (Figure 2.1 ).Beginning before age 20 and finishing after 60, a Bushong man is productively occupied almost twice as long as a Lele, the latter retiring comparatively early from a career that began well after physical maturity. Without intending to repeat Douglas's detailed analysis, some of the reasons might be noted briefly for their pertinence to the present discussion. One is the Lele practice of polygyny, which as a privilege of the elders entails for younger men a considerable postponement of marriage, hence of adult responsibilities.8 Moving into the political domain, Douglas's more general explanations of the Lele-Bushong contrast strike a note already familiar. But Douglas carries the analysis to new dimensions. It is not only differences in political scale or morphology that make one or another system more effective economically, but the different relations they entail between the powers that be and the process of production.9

8. This is not at all unique to Lele. Polygyny in a society of more or less balanced sex ratio usually means late first marriages for most men. While an only casual interest in production is not also necessary, it is at least consistent and often encountered. 9. Again I merely raise the point here, reserving it for fuller discussion later (Chapter 3).

Figure 2.1. Male Working-Span: Lele and Bushong (after Douglas, 1962, p. 231)

Scant use of young adult labor, however, is not characteristic of the Lele alone. It is not even the exclusive privilege of agricultural societies. Hunting and gathering do not demand of /Kung Bushmen that famous "maximum effort of a maximum number of people." They manage quite well without the full cooperation of younger men, who are fairly idle sometimes to the age of 251: Another significant feature of the composition of the [/Kung Bushmen] work force is the late assumption of adult responsibility by the adolescents. Young people are not expected to provide food regularly until they are married. Girls typically marry between the ages of IS and 20, and boys about five years later, so that it is not unusual to find healthy, active teenagers visiting from camp to camp while their older relatives provide food for them (Lee, 1968, p. 36). This contrast between the indolence of youth and industry of elders may appear also in a developed political setting, as in centralized African chiefdoms such as Bemba. Now the Bemba are not markedly polygynous. Audrey Richards proposes yet another explanation, one that calls to anthropological mind still other examples: In pre-European days there was a complete change of ambition between ... youth and age. The young boy, under the system of matrilocal marriage [entailing bride-service in the wife's family], had no individual responsibility for gardening. He was expected to cut trees [for making gardens], but his main way of advance in life was to attach himself to a chief or to a man of rank and not to make large gardens or to collect material goods. He often went on border raids or foraging expeditions. He did not expect to work in earnest until middle age, when his children were "crying from hunger" and he had settled down. Nowadays we saw in concrete cases the immense difference between the regularity of work done by the old and young.10 This is partly due to the new insubordination of the boys, but partly also to a perpetuation of an old tradition. In our society youths and adolescents have, roughly speaking, the same economic ambitions throughout youth and early manhood. . . . Among the Bemba this was not so, any more than it was among such warrior peoples as the Masai of East Africa with their regular age-sets.11 Each individual was expected to be first a fighter and later a cultivator and the father of a family (Richards, 1961, p. 402).

10. The concrete case described in greatest detail concerns the village of Kasaka, for which Richards recorded a general calendar of activities covering mainly September 1933, and work diaries of 38 adults over 23 days (Richards, 1961, pp. 162-64 and Table E). Only the old men worked regularly, "those reckoned by the Government as too feeble to pay tax." Richards observes: "Five old men worked 14 days out of 20; seven young men worked seven days out of 20 ... it is obvious that any community in which the young and active males work exactly half as much as the old must suffer as regards its food production" (p. 164 n). The records refer to a season of less-than-average agricultural intensity, but not the famous Bemba hunger period. 11. "The herding of livestock does not absorb the energies of the entire [Masai] population, and the young men from the ages of about sixteen to thirty live apart from their families and clans as warriors" (Forde, 1963 [1934], p. 29f).

In sum, for a variety of cultural reasons, the lifetime working span may be seriously curtailed. Indeed, economic obligations can be totally unbalanced in relation to physical capacity, the younger and stronger adults largely disengaged from production, leaving the burden of society's work to the older and weaker. An unbalance to the same effect may obtain in the division of labor by sex. Half the available labor power may be providing a disproportionately small fraction of the society's output. Differences of this kind are common enough, at least in the subsistence sector, to have long lent credence to crude materialist explanations of the customary descent rule, matrilineal or 'patrilineal, by the specific economic weight of female versus male labor. I have myself had ethnographic occasion to observe a marked unbalance in the sexual division of labor. Excluded from agriculture, the women of the Fijian island of Moala show much slighter interest than do their men in main productive activities. True that the women, especially younger women, maintain the homes, cook, fish periodically, and are charged with certain crafts. Yet the ease they enjoy by comparison with their sisters elsewhere in Fiji, where women do cultivate, is enough to credit the local saying that "in this land, women rest." One Moalan friend confided that all they really did was sit around all day and break wind. (This was a slander; gossip was the more consuming occupation.) The reverse emphasis, on female labor, is probably more widespread in primitive communities (exception made for pastoralists, where the women often—but sometimes many of the men too—are not concerned with the daily husbandry).12

12. Cf. Clark, 1938, p. 9; Rivers, 1906, pp. 566-67. As for middle-eastern Arabs, however, "The male Arab is quite content to pass the day smoking, chatting and drinking coffee. Herding the camels is his only office. All the work of erecting tents, looking after sheep and goats and bringing water, he leaves to his women" (Awad, 1962, p. 335).

One example we have already noted is worth repeating, as it again concerns hunters, who less than anyone might be thought able to afford the extravagance of one whole idle sex out of the two usually available. Yet such are the Hadza that the men pass six months a year (the dry season) in gambling—effectively inhibiting those who have lost their metal-tipped arrows from hunting big game the rest of the year (Woodburn, 1968, p. 54). It is impossible from these few instances to infer an extent, let alone attribute a universality, to the differential economic engagement by sex and age. Again I would merely raise a problem, which is also to cast a doubt on a common presupposition. The problem concerns the composition of the labor force. This composition is clearly a cultural and not simply a natural (physical) specification. Clearly too, the cultural and natural specifications need not correspond. By custom the individual working career is variously abbreviated or alleviated, and whole classes of the able-bodied, perhaps the most able-bodied, are exempted from economic concern. In the event, the disposable working force is something less than the available labor-power, and the remainder of the latter is otherwise spent or dissipated. That this diversion of manpower is sometimes necessary is not contested. It may well be functional, even inevitable, to the society and economy as organized. But that is the problem: we have to do with the organized withdrawal of important social energies from the economic process. Nor is it the only problem. Another is how much the others, the effective producers, actually do work. While no anthropologist today would concede the truth of the imperialist ideology that the natives are congenitally lazy, and many would testify rather that the people are capable of sustained labor, probably most would also observe that the motivation to do so is not constant, so that work is in fact irregular over the longer or shorter term. The work process is sensitive to interference of various kinds, vulnerable to suspension in, favor of other activities as serious as ritual, as frivolous as repose. The customary working day is often short; if it is protracted, frequently it is interrupted; if it is both long and unremitting, usually this is only seasonal. Within the community, moreover, some people work much more than others. By the norms of the society, let alone of the stakhonovite, considerable labor-power remains underemployed. As Maurice Godelier writes, labor is not a scarce resource in most primitive societies (1969, p. 32).13

13. Among Tiv, " "Labor' is the factor of production in greatest supply" (Bohannan and Bohannan, 1968, p. 76).

In the subsistence sector, a man's normal working day (in season) may be as short as four hours, as among the Bemba (Richards, 1961, pp. 398-399), the Hawaiians (Stewart, 1828, p. Ill) or the Kuikuru (Carneiro, 1968, p. 134), or perhaps it is six hours, as for/Kung Bushmen (Lee, 1968, p. 37) or Kapauku (Pospisil, 1963, pp. 144-145). Then again, it may last from early to late: But let us follow a (Tikopian) working party as they leave home on a fine morning, bound for the cultivations. They are going to dig turmeric, for it is August, the season for the preparation of this highly valued sacred dye. The group sets off from the village of Matautu, straggles along the beach to Rofaea and then turning inland begins to ascend the path running up to the crest of the hills. The turmeric plant ... grows on the mountain-side and to reach the orchard ... involves a steep climb of several hundred feet ... The party consists of Pa Nukunefu and his wife, their young daughter, and three older girls, these latter having been coopted from the households of friends and neighbors ... Soon after these people arrive they are joined by Vaitere, a youth whose family owns the neighbouring orchard ... The work is of very simple nature ... Pa Nukunefu and the women share the work fairly among them, he doing most of the clearing of vegetation and the digging, they some of the digging and replanting, and nearly all the cleaning and sorting ... the tempo of the work is an easy one. From time to time members of the party drop out for a rest, and to chew betel. To this end, Vaitere, who takes no very active part in the work itself, climbs a nearby tree to collect some leaves of pita, the betel plant.... About mid-morning the customary refreshment is provided in the shape of green coconuts, for which Vaitere is again sent to climb .... The whole atmosphere is one of labour diversified by recreation at will.... Vaitere, as the morning draws on, busies himself with the construction of a cap out of banana leaf, his own invention, and of no practical use… So between work and leisure the time passes, until as the sun declines perceptibly from the zenith the task of the party is done, and bearing their baskets of turmeric roots they go off down the mountain-side to their homes (Firth, 1936, pp. 92-93.). On the other hand, the daily labors of Kapauku seem more sustained. Their workday begins about 7:30 a.m. and proceeds fairly steadily until a late morning break for lunch. The men return to the village in the early afternoon, but the women continue on until four or five o'clock. Yet the Kapauku "have a conception of balance in life": if they work strenuously one day, they rest the next. Since the Kapauku have a conception of balance in life, only every other day is supposed to be a working day. Such a day is followed by a day of rest in order to "regain the lost power and health." This monotonous fluctuation of leisure and work is made more appealing to the Kapauku by inserting into their schedule periods of more prolonged holidays (spent in dancing, visiting, fishing, or hunting...). Consequently, we usually find only some of the people departing for their gardens in the morning, the others are taking their "day off." However, many individuals do not rigidly conform to this ideal. The more conscientious cultivators often work intensively for several days in order to complete clearing a plot, making a fence, or digging a ditch. After such a task is accomplished, they relax for a period of several days, thus compensating for their "missed" days of rest (Pospisil, 1963, p. 145). Following this course of moderation in all things, Kapauku over the long run allow an unextraordinary amount of time to agriculture. From records that he kept through an eight-month period (Kapauku cultivation is not seasonal) and on the assumption of a potential eight-hour day, Pospisil estimates that Kapauku men spend approximately one-fourth their "working time" in gardening, the women about one-fifth. More precisely, men average 2hl8m/day in agricultural tasks, the women lh42m. Pospisil writes: "These relatively small portions of total working time seem to cast serious doubt on the claim, so often made, that native cultivation methods are wasteful, time consuming and economically inadequate" (1963, p. 164). For the rest, aside from relaxation and "prolonged holidays," Kapauku men are more concerned with politicking and exchange than with other areas of production (crafts, hunting, house building).14

14. Here is another society, however, in which labor obligation seems unevenly divided by sex, and also by age-class. For in addition to gardening, Kapauku women do a substantial amount of fishing, pig tending,and housework, even as their men are sometimes away three and four months in trading or war expeditions, and the unmarried men in particular maintain all the while a steady indifference to cultivation (Pospi-sil, 1963, p. 189).

In their studied habit of one day on, one day off, Kapauku are perhaps unusual for the regularity of their economic tempo,15 but not for its intermittency. A similar pattern was documented in Chapter One for hunters: Australians, Bushmen, and other peoples—their labors chronically punctuated by days of slack, not to mention sleep. And notoriously among many agriculturalists of seasonal regime the same cadence recurs, although on a different time scale. Agricultural off-seasons are given over as much to relaxation and diversion, to rest, ceremony and visiting, as they are to other works. Taken over the extended term, therefore, all these modes of livelihood reveal themselves unintensive: they make only fractional demands on the available labor-power.

15. Although Tiv also "prefer to work very hard and at a terrific pace and then do almost nothing for a day or two" (Bohannan and Bohannan, 1968, p. 72).

Fractional use of labor-power is detectable also in the individual work-diaries sometimes collected by ethnographers. Although these diaries typically account for only a very few people as well as a very brief time, they are usually extensive enough to show important domestic differences in economic effort. At least one of the six or seven people concerned turns out to be the village indolent (cf. Provinse, 1937; Titiev, 1944, p. 196). The diaries thus manage to convey a suggestion of unequal productive commitment, that is to say, a relative underemployment of some even within the unspectacular conscientiousness of all. A certain flavor of this pattern, if not an accurate measure, is provided in Table 2.3, a reproduction of F. Nadel's journal for three Nupe farm families (1942, pp. 222-224).,16 The two weeks of observation fall into different periods of the annual cycle. The second week is a time of peak intensity.

16. Of course, even as there remains a question whether such a slight record can be representative of the Nupe economic condition, it is also questionable whether Nupe are truly representative of a primitive economy.

Table 2.3. Journal of three Nupe farm families (after Nadel 1942, pp. 222-224)

Audrey Richard's diaries for two Bemba villages lend themselves to quantitative assessment. The first and longer, from Kasaka village, is presented in Table 2.4: it covers the activities of 38 adults over 23 days (September 13-October 5, 1934). This was a season of reduced agricultural labor, although not the Bemba hungry period. Men engaged in little or no work for approximately 45 percent of the time. Only half their days could be classed as productive or working days, of an average duration of 4.72 hours of labor (but see below, where the figure of 2.75 hours for a working day was apparently calculated on a base of all available days). Women's time was more equally divided between working days (30.3 percent), days of part-time work (35.1 percent) and days of little or no work (31.7 percent). For both men and women, this unstrenuous program would be modified during the busier agricultural season.17 Table 2.5, representing the work of 33 adults of Kampamba village over seven to ten days of January 1934, attests to the periodic intensification of productive tempo.18

Date: 2014-12-21; view: 977

|