CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Subsistence

When Herskovits was writing his Economic Anthropology (1958), it was common anthropological practice to take the Bushmen or the native Australians as "a classic illustration of a people whose economic resources are of the scantiest," so precariously situated that "only the most intense application makes survival possible." Today the "classic" understanding can be fairly reversed—on evidence largely from these two groups. A good case can be made that hunters and gatherers work less than we do; and, rather than a continuous travail, the food quest is intermittent, leisure abundant, and there is a greater amount of sleep in the daytime per capita per year than in any other condition of society.

Some of the substantiating evidence for Australia appears in early sources, but we are fortunate especially to have now the quantitative materials collected by the 1948 American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land. Published in 1960, these startling data must provoke some review of the Australian reportage going back for oyer a century, and perhaps revision of an even longer period of anthropological thought. The key research was a temporal study of hunting and gathering by McCarthy and McArthur (1960), coupled to Mc-Arthur's analysis of the nutritional outcome.

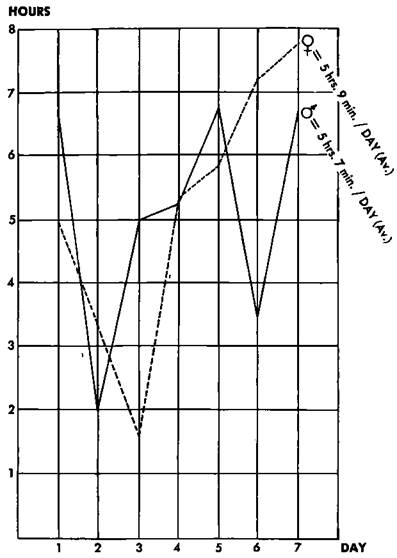

Figures 1.1 and 1.2 summarize the principal production studies. These were short-run observations taken during nonceremonial periods. The record for Fish Creek (14 days) is longer as well as more detailed than that for Hemple Bay (seven days). Only adults' work has been reported, so far as I can tell. The diagrams incorporate information on hunting, plant collecting, preparing foods and repairing weapons, as tabulated by the ethnographers. The people in both camps were free-ranging native Australians, living outside mission or other settlements during the period of study, although such was not necessarily their permanent or even their ordinary circumstance.13

13. Fish Creek was an inland camp in western Arnhem Land consisting of six adult males and three adult females. Hemple Bay was a coastal occupation on Groote Eylandt; there were four adult males, four adult females,and five juveniles and infants in the camp. Fish Creek was investigated at the end of the dry season, when the supply of vegetable foods was low; kangaroo hunting was rewarding, although the animals became increasingly wary under steady stalking. At Hemple Bay, vegetable foods were plentiful; the fishing was variable but on the whole good by comparison with other coastal camps visited by the expedition. The resource base at Hemple Bay was richer than at Fish Creek. The greater time put into food-getting at Hemple Bay may reflect, then, the support of five children. On the other hand, the Fish Creek group did maintain a virtually full-time specialist, and part of the difference in hours worked may represent a normal coastal-inland variation. In inland hunting, good things often come in large packages; hence, one day's work may yield two day's sustenance. A fishing-gathering regime perhaps produces smaller if steadier returns, enjoining somewhat longer and more regular efforts.

Figure 1.1. Hours per Day in Food-Connected Activities: Fish Creek Group (McCarthy and McArthur, 1960)

Figure 1.2. Hours per Day in Food-Connected Activities: Hemple Bay Group (McCarthy and McArthur, 1960)

One must have serious reservations about drawing general or historical inferences from the Arnhem Land data alone. Not only was the context less than pristine and the time of study too brief, but certain elements of the modern situation may have raised productivity above aboriginal levels: metal tools, for example, or the reduction of local pressure on food resources by depopulation. And our uncertainty seems rather doubled than neutralized by other current circumstances that, conversely, would lower economic efficiency: these semi-independent hunters, for instance, are probably not as skilled as their ancestors. For the moment, let us consider the Arnhem Land conclusions as experimental, potentially credible in the measure they are supported by other ethnographic or historic accounts.

The most obvious, immediate conclusion is that the people do not work hard. The average length of time per person per day put into the appropriation and preparation of food was four or five hours. Moreover, they do not work continuously. The subsistence quest was highly intermittent. It would stop for the time being when the people had procured enough for the time being, which left them plenty of time to spare. Clearly in subsistence as in other sectors of production, we have to do with an economy of specific, limited objectives. By hunting and gathering these objectives are apt to be irregularly accomplished, so the work pattern becomes correspondingly erratic.

In the event, a third characteristic of hunting and gathering un-imagined by the received wisdom: rather than straining to the limits of available labor and disposable resources, these Australians seem to underuse their objective economic possibilities.

The quantity of food gathered in one day by any of these groups could in every instance have been increased. Although the search for food was, for the women, a job that went on day after day without relief [but see our Figures 1.1 and 1.2], they rested quite frequently, and did not spend all the hours of daylight searching for and preparing food. The nature of the men's food-gathering was more sporadic, and if they had a good catch one day they frequently rested the next. . . . Perhaps unconsciously they weigh the benefit of greater supplies of food against the effort involved in collecting it, perhaps they judge what they consider to be enough, and when that is collected they stop (McArthur, 1960, p. 92).

It follows, fourthly, that the economy was not physically demanding. The investigators' daily journal indicates that the people pace themselves; only once is a hunter described as "utterly exhausted" (McCarthy and Mc Arthur, 1960, pp. 150f). Neither did the Arnhem Landers themselves consider the task of subsistence onerous. "They certainly did not approach it as an unpleasant job to be got over as soon as possible, nor as a necessary evil to be postponed as long as possible" (McArthur, 1960, p. 92).14

14. At least some Australians, the Yir-Yiront, make no linguistic differentiation between work and play (Sharp, 1958, p. 6).

In this connection, and also in relation to their underuse of economic resources, it is noteworthy that the Arnhem Land hunters seem not to have been content with a "bare existence." Like other Australians (cf. Worsley, 1961, p. 173), they become dissatisfied with an unvarying diet; some of their time appears to have gone into the provision of diversity over and above mere sufficiency (McCarthy and McArthur, 1960, p. 192).

In any case, the dietary intake of the Arnhem Land hunters was adequate—according to the standards of the National Research Council of America. Mean daily consumption per capita at Hemple Bay was 2,160 calories (only a four-day period of observation), and at Fish Creek 2,130 calories (11 days). Table 1.1 indicates the main daily consumption of various nutrients, calculated by McArthur in percentages of the NRCA recommended dietary allowances.

Table 1.1 Mean daily consumption as percentage of recommended allowances (from McArthur, 1960)

| Calories | Protein | Iron | Calcium | Ascorbic Acid | |

| Hemple Bay | |||||

| Fish Creek |

Finally, what does the Arnhem Land study say about the famous question of leisure? It seems that hunting and gathering can afford extraordinary relief from economic cares. The Fish Creek group maintained a virtually full-time craftsman, a man 35 or 40 years old, whose true specialty however seems to have been loafing:

He did not go out hunting at all with the men, but one day he netted fish most vigorously. He occasionally went into the bush to get wild bees' nests. Wilira was an expert craftsman who repaired the spears and spear-throwers, made smoking-pipes and drone-tubes, and hafted a stone axe (on request) in a skillful manner; apart from these occupations he spent most of his time talking, eating and sleeping (McCarthy and McArthur, 1960, p. 148).

Wilira was not altogether exceptional. Much of the time spared by the Arnhem Land hunters was literally spare time, consumed in rest and sleep (see Tables 1.2 and 1.3). The main alternative to work, changing off with it in a complementary way, was sleep:

Apart from the time (mostly between definitive activities and during cooking periods) spent in general social intercourse, chatting, gossiping and so on, some hours of the daylight were also spent resting and sleeping. On the average, if the men were in camp, they usually slept after lunch from an hour to an hour and a half, or sometimes even more. Also after returning from fishing or hunting they usually had a sleep, either immediately they arrived or whilst game was being cooked. At Hemple Bay the men slept if they returned early in the day but not if they reached camp after 4.00 p.m. When in camp all day they slept at odd times and always after lunch. The women, when out collecting in the forest, appeared to rest more frequently than the men. If in camp all day, they also slept at odd times, sometimes for long periods (McCarthy and McArthur, 1960, p. 193).

Table 1.2. Daytime rest and sleep, Fish Creek group (data from McCarthy and McArthur, 1960)

| Day | Male Average | Female A verage |

| 2'15" | 2'45" | |

| l'30'f | l'0" | |

| Most of the day | ||

| Intermittent | ||

| Intermittent and most of late afternoon | ||

| Most of the day | ||

| Several hours | ||

| 2'0" | 2'0" | |

| 50" | 50" | |

| Afternoon | ||

| Afternoon | ||

| Intermittent, afternoon | ||

| — | — | |

| 3'15" | 3'15" |

Table 1.3. Daytime rest and sleep, Hemple Bay group (data from McCarthy and McArthur, 1960)

| Day | Male verage | Female Average |

| — | 45" | |

| Most of the day | 2'45" | |

| l'0" | — | |

| Intermittent | Intermittent | |

| — | 1'30" | |

| Intermittent | Intermittent | |

| Intermittent | Intermittent |

The failure of Arnhem Landers to "build culture" is not strictly from want of time. It is from idle hands.

So much for the plight of hunters and gatherers in Arnhem Land. As for the Bushmen, economically likened to Australian hunters by Herskovits, two excellent recent reports by Richard Lee show their condition to be indeed the same (Lee, 1968; 1969). Lee's research merits a special hearing not only because it concerns Bushmen, but specifically the Dobe section of/Kung Bushmen, adjacent to the Nyae Nyae about whose subsistence—in a context otherwise of "material plenty"—Mrs. Marshall expressed important reservations. The Dobe occupy an area of Botswana where/Kung Bushmen have been living for at least a hundred years, but have only just begun to suffer dislocation pressures. (Metal, however, has been available to the Dobe since 1880-90). An intensive study was made of the subsistence production of a dry season camp with a population (41 people) near the mean of such settlements. The observations extended over four weeks during July and August 1964, a period of transition from more to less favorable seasons of the year, hence fairly representative, it seems, of average subsistence difficulties.

Despite a low annual rainfall (6 to 10 inches), Lee found in the Dobe area a "surprising abundance of vegetation." Food resources were "both varied and abundant," particularly the energy-rich man-getti nut—"so abundant that millions of the nuts rotted on the ground each year for want of picking" ( all references in Lee, 1969, p. 59).15 His reports on time spent in food-getting are remarkably close to the Arnhem Land observations. Table 1.4 summarizes Lee's data.

15. This appreciation of local resources is all the more remarkable considering that Lee's ethnographic work was done in the second and third years of "one of the most severe droughts in South Africa's history" (1968, p. 39; 1969, p. 73 n.).

The Bushman figures imply that one man's labor in hunting and gathering will support four or five people. Taken at face value, Bushman food collecting is more efficient than French farming in the period up to World War II, when more than 20 percent of the population were engaged in feeding the rest. Confessedly, the comparison is misleading, but not as misleading as it is astonishing. In the total population of free-ranging Bushmen contacted by Lee, 61.3 percent (152 of 248) were effective food producers; the remainder were too young or too old to contribute importantly. In the particular camp under scrutiny, 65 percent were "effectives." Thus the ratio of food producers to the general population is actually 3 :5 or 2 : 3. But, these 65 percent of the people "worked 36 percent of the time, and 35 percent of the people did not work at all"! (Lee, 1969, p. 67).

For each adult worker, this comes to about two and one-half days labor per week. ("In other words, each productive individual supported herself or himself and dependents and still had 3-1/2 to 5-1/2 days available for other activities.") A "day's work" was about six hours; hence the Dobe work week is approximately 15 hours, or an average of 2 hours 9 minutes per day. Even lower than the Arnhem Land norms, this figure however excludes cooking and the preparation of implements. All things considered, Bushmen subsistence labors are probably very close to those of native Australians.

Table 1.4. Summary ofDobe Bushmen work diary (from Lee, 1969)

| Week | Mean Group Size* | Man-Days of Consumption ** | Man-Days of Work | Days of Work/ Week/Adult | Index of Subsistence Effort** |

| 1 (July 6-12) | 25.6 (23-29) | 2.3 | .21 | ||

| 2 (July 13-19) | 28.3 (23-37) | 1.2 | .11 | ||

| 3 (July 20-26) | 34.3 (29-40) | 1.9 | .18 | ||

| 4 (July 27-Aug. 2) | 35.6 (32-40) | 3.2 | .31 | ||

| 4-week totals | 30.9 | 2.2 | .21 | ||

| Adjusted totals § | 31.8 | 2.5 | .23 |

*Group size shown in average and range. There is considerable short-term population fluctuation in Bushmen camps.

** Includes both children and adults, to give a combined total of days of provisioning required/week.

** This index was constructed by Lee to illustrate the relation between consumption and the work required to produce it: S = W/C, where W = number of man-days of work, and C = man days of consumption. Inverted, the formula would tell how many people could be supported by a day's work in subsistence.

§ Week 2 was excluded from the final calculations because the investigator contributed some food to the camp on two days.

Also like the Australians, the time Bushmen do not work in subsistence they pass in leisure or leisurely activity. One detects again that characteristic paleolithic rhythm of a day or two on, a day or two off—the latter passed desultorily in camp. Although food collecting is the primary productive activity, Lee writes, "the majority of the people's time (four to five days per week) is spent in other pursuits, such as resting in camp or visiting other camps" (1969, p. 74):

A woman gathers on one day enough food to feed her family for three days, and spends the rest of her time resting in camp, doing embroidery, visiting other camps, or entertaining visitors from other camps. For each day at home, kitchen routines, such as cooking, nut cracking, collecting firewood, and fetching water, occupy one to three hours of her time. This rhythm of steady work and steady leisure is maintained throughout the year. The hunters tend to work more frequently than the women, but their schedule is uneven. It is not unusual for a man to hunt avidly for a week and then do no hunting at all for two or three weeks. Since hunting is an unpredictable business and subject to magical control, hunters sometimes experience a run of bad luck and stop hunting for a month or longer. During these periods, visiting, entertaining, and especially dancing are the primary activities of men (1968, p. 37),

The daily per-capita subsistence yield for the Dobe Bushmen was 2,140 calories. However, taking into account body weight, normal activities, and the age-sex composition of the Dobe population, Lee estimates the people require only 1,975 calories per capita. Some of the surplus food probably went to the dogs, who ate what the people left over. "The conclusion can be drawn that the Bushmen do not lead a substandard existence on the edge of starvation as has been commonly supposed" (1969, p. 73).

Taken in isolation, the Arnhem Land and Bushmen reports mount a disconcerting if not decisive attack on the entrenched theoretical position. Artificial in construction, the former study in particular is reasonably considered equivocal. But the testimony of the Arnhem Land expedition is echoed at many points by observations made elsewhere in Australia, as well as elsewhere in the hunting-gathering world. Much of the Australian evidence goes back to the nineteenth century, some of it to quite acute observers careful to make exception of the aboriginal come into relation with Europeans, for "his food supply is restricted, and ... he is in many cases warned off from the waterholes which are the centers of his best hunting grounds" (Spencer and Gillen, 1899, p. 50).

The case is altogether clear for the well-watered areas of southeastern Australia. There the Aboriginals were favored with a supply of fish so abundant and easily procured that one squatter on the Victorian scene of the 1840s had to wonder "how that sage people managed to pass their time before my party came and taught them to smoke" (Curr, 1965, p. 109). Smoking at least solved the economic problem— nothing to do: "That accomplishment fairly acquired ... matters went on flowingly, their leisure hours being divided between putting the pipe to its legitimate purpose and begging my tobacco." Somewhat more seriously, the old squatter did attempt an estimate of the amount of time spent in hunting and gathering by the people of the then Port Phillip's District. The women were away from the camp on gathering expeditions about six hours a day, "half of that time being loitered away in the shade or by the fire"; the men left for the hunt shortly after the women quit camp and returned around the same time (p. 118). Curr found the food thus acquired of "indifferent quality" although "readily procured," the six hours a day "abundantly sufficing" for that purpose; indeed the country "could have supported twice the number of Blacks we found in it" (p. 120). Very similar comments were made by another old-timer, Clement Hodgkinson, writing of an analogous environment in northeastern New South Wales. A few minutes fishing would provide enough to feed "the whole tribe" (Hodgkinson, 1845, p. 223; cf. Hiatt, 1965, pp. 103-104). "Indeed, throughout all the country along the eastern coast, the blacks have never suffered so much from scarcity of food as many commiserating writers have supposed" (Hodgkinson, 1845, p. 227).

But the people who occupied these more fertile sections of Australia, notably in the southeast, have not been incorporated in today's stereotype of an Aborigine. They were wiped out early.16 The European's relation to such "Blackfellows" was one of conflict over the continent's riches; little time or inclination was spared from the process of destruction for the luxury of contemplation. In the event, ethnographic consciousness would only inherit the slim pickings: mainly interior groups, mainly desert people, mainly the Arunta. Not that the Arunta are all that bad off—ordinarily, "his life is by no means a miserable or a very hard one" (Spencer and Gillen, 1899, p. 7).17

16. As were the Tasmanians, of whom Bonwick wrote: "The Aborigines were never in want of food; though Mrs. Somerville has ventured to say of them in her 'Physical Geography' that they were 'truly miserable in a country where the means of existence were so scanty.' Dr. Jeannent, once Protector, writes: 'They must have been superabundantly supplied, and have required little exertion or industry to support themselves.* "(Bonwick, 1870, p. 14).

17. This by way of contrast to other tribes deeper in the Central Australian Desert, and specifically under "ordinary circumstances," not the times of long-continued drought when "he has to suffer privation" (Spencer and Gillen, 1899, p. 7).

But the Central tribes should not be considered, in point of numbers or ecological adaptation, typical of native Australians (cf. Meggitt, 1964). The following tableau of the indigenous economy provided by John Edward Eyre, who had traversed the south coast and penetrated the Flinders range as well as sojourned in the richer Murray district, has the right to be acknowledged at least as representative:

Throughout the greater portion of New Holland, where there do not happen to be European settlers, and invariably when fresh water can be permanently procured upon the surface, the native experiences no difficulty whatever in procuring food in abundance all the year round. It is true that the character of his diet varies with the changing seasons, and the formation of the country he inhabits; but it rarely happens that any season of the year, or any description of country does not yield him both animal and vegetable food… Of these [chief] articles [of food], many are not only procurable in abundance, but in such vast quantities at the proper seasons, as to afford for a considerable length of time an ample means of subsistence to many hundreds of natives congregated at one place. ... On many parts of the coast, and in the larger inland rivers, fish are obtained of a very fine description, and in great abundance. At Lake Victoria ... I have seen six hundred natives encamped together, all of whom were living at the time upon fish procured from the lake, with the addition, perhaps, of the leaves of the mesembryanthemum. When I went amongst them I never perceived any scarcity in their camps.... At Moorunde, when the Murray annually inundates the flats, fresh-water cray-fish make their way to the surface of the ground... in such vast numbers that I have seen four hundred natives live upon them for weeks together, whilst the numbers spoiled or thrown away would have sustained four hundred more. ... An unlimited supply of fish is also procurable at the Murray about the beginning of December. . . . The number [of fish] procured ... in a few hours is incredible. . . . Another very favourite article of food, and equally abundant at a particular season of the year, in the eastern portion of the continent, is a species of moth which the natives procure from the cavities and hollows of the mountains in certain localities. . . . The tops, leaves, and stalks of a kind of cress, gathered at the proper season of the year . . . furnish a favourite, and inexhaustible supply of food for an unlimited number of natives. . . . There are many other articles of food among the natives, equally abundant and valuable as those I have enumerated (Eyre, 1845, vol. 2, pp. 250-254).

Both Eyre and Sir George Grey, whose sanguine view of the indigenous economy we have already noted ("I have always found the greatest abundance in their huts") left specific assessments, in hours per day, of the Australians' subsistence labors. (This in Grey's case would include inhabitants of quite undesirable parts of western Australia.) The testimony of these gentlemen and explorers accords very closely with the Arnhem Land averages obtained by McCarthy and McArthur. "In all ordinary seasons," wrote Grey, (that is, when the people are not confined to their huts by bad weather) "they can obtain, in two or three hours a sufficient supply of food for the day, but their usual custom is to roam indolently from spot to spot, lazily collecting it as they wander along" (1841, vol. 2, p. 263; emphasis mine). Similarly, Eyre states: "In almost every part of the continent which I have visited, where the presence of Europeans, or their stock, has not limited, or destroyed their original means of subsistence, I have found that the natives could usually, in three or four hours, procure as much food as would last for the day, and that without fatigue or labour" (1845, pp. 254-255; emphasis mine).

The same discontinuity of subsistence of labor reported by McArthur and McCarthy, the pattern of alternating search and sleep, is repeated, furthermore, in early and late observations from all over the continent (Eyre, 1845, vol. 2, pp. 253-254; Bulmer, in Smyth, 1878, vol. 1, p. 142; Mathew, 1910, p. 84; Spencer and Gillen, 1899, p. 32; Hiatt, 1965, pp. 103-104). Basedow took it as the general custom of the Aboriginal: "When his affairs are working harmoniously, game secured, and water available, the aboriginal makes his life as easy as possible; and he might to the outsider even appear lazy" (1925, p. 116).18

18. Basedow goes on to excuse the people's idleness on the grounds of overeating, then to excuse the overeating on the grounds of the periods of hunger natives suffer, which he further explains by the droughts Australia is heir to, the effects of which have been exacerbated by the white man's exploitation of the country.

Meanwhile, back in Africa the Hadza have been long enjoying a comparable ease, with a burden of subsistence occupations no more strenuous in hours per day than the Bushmen or the Australian Aboriginals (Woodburn, 1968). Living in an area of "exceptional abundance" of animals and regular supplies of vegetables (the vicinity of Lake Eyasi). Hadza men seem much more concerned with games of chance than with chances of game. During the long dry season especially, they pass the greater part of days on end in gambling, perhaps only to lose the metal-tipped arrows they need for big game hunting at other times. In any case, many men are "quite unprepared or unable to hunt big game even when they possess the necessary arrows." Only a small minority, Woodburn writes, are active hunters of large animals, and if women are generally more assiduous at their vegetable collecting, still it is at a leisurely pace and without prolonged labor (cf. p. 51; Woodburn, 1966). Despite this nonchalance, and an only limited economic cooperation, Hadza "nonetheless obtain sufficient food without undue effort." Woodburn offers this "very rough approximation" of subsistence-labor requirements: "Over the year as a whole probably an average of less than two hours a day is spent obtaining food" (Woodburn, 1968, p. 54).

Interesting that the Hadza, tutored by life andnotby anthropology, reject the neolithic revolution in order to keep their leisure. Although surrounded by cultivators, they have until recently refused to take up agriculture themselves, "mainly on the grounds that this would involve too much hard work."19 In this they are like the Bushmen, who respond to the neolithic question with another: "Why should we plant, when there are so many mongomongo nuts in the world?" (Lee, 1968, p. 33). Woodburn moreover did form the impression, although as yet unsubstantiated, that Hadza actually expend less energy, and probably less time, in obtaining subsistence than do neighboring cultivators of East Africa (1968, p. 54).20

19. This phrase appears in a paper by Woodburn distributed to the Wenner-Gren symposium on "Man the Hunter," although it is only elliptically repeated in the published account (1968, p. 55). I hope I do notcommitan indiscretion or an inaccuracy citing it here.

20. "Agriculture is in fact the first example of servile labor in the history of man. According to biblical tradition, the first criminal, Cain, is a farmer" (Lafargue, 19U[1883], p. 11 n.). It is notable too that the agricultural neighbours of both Bushmen and Hadza are quick to resort to the more dependable hunting-gathering life come drought and threat of famine (Woodbum, 1958, p. 54; Lee, 1968, pp. 39-40).

To change continents but not contents, the fitful economic commitment of the South American hunter, too, could seem to the European outsider an incurable "natural disposition":

. . . the Yamana are not capable of continuous, daily hard labor, much to the chagrin of European farmers and employers for whom they often work. Their work is more a matter of fits and starts, and in these occasional efforts they can develop considerable energy for a certain time. After that, however, they show a desire for an incalculably long rest period during which they lie about doing nothing, without showing great fatigue. ... It is obvious that repeated irregularities of this kind make the European employer despair, but the Indian cannot help it. It is his natural disposition (Gusinde, 1961, p. 27).21

21. This common distaste for prolonged labor manifested by recently primitive peoples under European employ, a distaste not restricted to ex-hunters, might have alerted anthropology to the fact that the traditional economy had known only modest objectives, so within reach as to allow an extraordinary disengagement, considerable "relief from the mere problem of getting a living." The hunting economy may also be commonly underrated for its presumed inability to support specialist production. Cf. Sharp, 1934-35, p. 37; Radcliffe-Brown, 1948, p. 43; Spencer, 1959, pp. 155,196,251; Lothrup, 1928, p. 71; Steward, 1938, p. 44. If there is not specialization, at any rate it is clearly for lack of a "market," not for lack of time.

The hunter's attitude towards farming introduces us, lastly, to a few particulars of the way they relate to the food quest. Once again we venture here into the internal realm of the economy, a realm sometimes subjective and always difficult to understand; where, moreover, hunters seem deliberately inclined to overtax our comprehension by customs so odd as to invite the'extreme interpretation that either these people are fools or they really have nothing to worry about. The former would be a true logical deduction from the hunter's nonchalance, on the premise that his economic condition is truly exigent. On the other hand, if a livelihood is usually easily procured, if one can usually expect to succeed, then the people's seeming imprudence can no longer appear as such. Speaking to unique developments of the market economy, to its institutionalization of scarcity, Karl Polanyi said that our "animal dependence upon food has been bared and the naked fear of starvation permitted to run loose. Our humiliating enslavement to the material, which all human culture is designed to mitigate, was deliberately made more rigorous" (1947, p. 115). But our problems are not theirs, the hunters and gatherers. Rather, a pristine affluence colors their economic arrangements, a trust in the abundance of nature's resources rather than despair at the inadequacy of human means. My point is that otherwise curious heathen devices become understandable by the people's confidence, a confidence which is the reasonable human attribute of a generally successful economy.22

22. At the same time that the bourgeois ideology of scarcity was let loose, with the inevitable effect of downgrading an earlier culture, it searched and found in nature the ideal model to follow if man (or at least the workingman) was ever to better his unhappy lot: the ant, the industrious ant. In this the ideology may have been as mistaken as in its view of hunters. The following appeared in the Ann Arbor News, January 27, 1971, under the head, "Two Scientists Claim Ants a little Lazy": Palm Springs, Calif. (AP)—"Ants aren't all they are reported [reputed?] to be," say Drs. George and Jeanette Wheeler.

Consider the hunter's chronic movements from camp to camp. This nomadism, often taken by us as a sign of a certain harassment, is undertaken by them with a certain abandon. The Aboriginals of Victoria, Smyth recounts, are as a rule "lazy travellers. They have no motive to induce them to hasten their movements. It is generally late in the morning before they start on their journey, and there are many interruptions by the way" (1878, vol. 1, p. 125; emphasis mine). The good Pere Biard in his Relation of 1616, after a glowing description of the foods available in their season to the Micmac ("Never had Solomon his mansion better regulated and provided with food ") goes on in the same tone:

In order to thoroughly enjoy this, their lot, our foresters start off to their different places with as much pleasure as if they were going on a stroll or an excursion; they do this easily through the skillful use and great convenience of canoes ... so rapidly sculled that, without any effort, in good weather you can make thirty or forty leagues a day; nevertheless we scarcely see these Savages posting along at this rate, for their days are all nothing but pastime. They are never in a hurry. Quite different from us, who can never do anything without hurry and worry . . . (Biard, 1897, pp. 84-85).

The husband-wife researchers have devoted years to studying the creatures, heroes of fables on industriousness.

"Whenever we view an anthill we get the impression of a tremendous amount of activity, but that is merely because there are so many ants and they all look alike," the Wheelers concluded.

"The individual ants spend a great deal of time just loafing. And, worse than that, the worker ants, who are all females, spend a lot of time primping."

Certainly, hunters quit camp because food resources have given out in the vicinity. But to see in this nomadism merely a flight from starvation only perceives the half of it; one ignores the possibility that the people's expectations of greener pastures elsewhere are not usually disappointed. Consequently their wanderings, rather than anxious, take on all the qualities of a picnic outing on the Thames.

A more serious issue is presented by the frequent and exasperated observation of a certain "lack of foresight" among hunters and gatherers. Oriented forever in the present, without "the slightest thought of, or care for, what the morrow may bring" (Spencer and Gillen, 1899, p. 53), the hunter seems unwilling to husband supplies, incapable of a planned response to the doom surely awaiting him. He adopts instead a studied unconcern, which expresses itself in two complementary economic inclinations.

The first, prodigality: the propensity to eat right through all the food in the camp, even during objectively difficult times, "as if," LeJeune said of the Montagnais, "the game they were to hunt was shut up in a stable." Basedow wrote of native Australians, their motto "might be interpreted in words to the effect that while there is plenty for today never care about tomorrow. On this account an Aboriginal is inclined to make one feast of his supplies, in preference to a modest meal now and another by and by" (1925, p. 116). LeJeune even saw his Montagnais carry such extravagance to the edge of disaster:

In the famine through which we passed, if my host took two, three, or four Beavers, immediately, whether it was day or night, they had a feast for all neighboring Savages. And if those people had captured something, they had one also at the same time; so that, on emerging from one feast, you went to another, and sometimes even to a third and a fourth. I told them that they did not manage well, and that it would be better to reserve these feasts for future days, and in doing this they would not be so pressed with hunger. They laughed at me. "Tomorrow" (they said) "we shall make another feast with what we shall capture." Yes, but more often they capture only cold and wind (LeJeune, 1887, pp. 281-283).

Sympathetic writers have tried to rationalize the apparent impracti-cality. Perhaps the people have been carried beyond reason by hunger: they are apt to gorge themselves on a kill because they have gone so long without meat—and for all they know they are likely to soon do so again. Or perhaps in making one feast of his supplies a man is responding to binding social obligations, to important imperatives of sharing. LeJeune's experience would confirm either view, but it also suggests a third. Or rather, the Montagnais have their own explanation. They are not worried by what the morrow may bring because as far as they are concerned it will bring more of the same: "another feast." Whatever the value of other interpretations, such self-confidence must be brought to bear on the supposed prodigality of hunters. More, it must have some objective basis, for if hunters and gatherers really favored gluttony over economic good sense, they would never have lived to become the prophets of this new religion.

A second and complementary inclination is merely prodigality's negative side: the failure to put by food surpluses, to develop food storage. For many hunters and gatherers, it appears, food storage cannot be proved technically impossible, nor is it certain that the people are unaware of the possibility (cf. Woodburn, 1968, p. 53). One must investigate instead what in the situation precludes the attempt. Gusinde asked this question, and for the Yahgan found the answer in the selfsame justifiable optimism. Storage would be "superfluous," because throughout the entire year and with almost limitless generosity the sea puts all kinds of animals at the disposal of the man who hunts and the woman who gathers. Storm or accident will deprive a family of these things for no more than a few days. Generally no one need reckon with the danger of hunger, and everyone almost anywhere finds an abundance of what he needs. Why then should anyone worry about food for the future! . . . Basically our Fuegians know that they need not fear for the future, hence they do not pile up supplies. Year in and year out they can look forward to the next day, free of care. . . . (Gusinde, 1961, pp. 336, 339).

Gusinde's explanation is probably good as far as it goes, but probably incomplete. A more complex and subtle economic calculus seems in play—realized however by a social arithmetic exceedingly simple. The advantages of food storage should be considered against the diminishing returns to collection within the compass of a confined locale. An uncontrollable tendency to lower the local carrying capacity is for hunters au fond des choses: a basic condition of their production and main cause of their movement. The potential drawback of storage is exactly that it engages the contradiction between wealth and mobility. It would anchor the camp to an area soon depleted of natural food supplies. Thus immobilized by their accumulated stocks, the people may suffer by comparison with a little hunting and gathering elsewhere, where nature has, so to speak, done considerable storage of her own—of foods possibly more desirable in diversity as well as amount than men can put by. But this fine calculation—in any event probably symbolically impossible (cf. Codere,1968)—would be worked out in a much simpler binary opposition, set in social terms such as "love" and "hate." For as Richard Lee observes (1969, p. 75), the technically neutral activity of food accumulation or storage is morally something else again, "hoarding." The efficient hunter who would accumulate supplies succeeds at the cost of his own esteem, or else he gives them away at the cost of his (superfluous) effort. As it works out, an attempt to stock up food may only reduce the overall output of a hunting band, for the have-nots will content themselves with staying in camp and living off the wherewithal amassed by the more prudent. Food storage, then, may be technically feasible, yet economically undesirable, and socially unachievable.

If food storage remains limited among hunters, their economic confidence, born of the ordinary times when all the people's wants are easily satisfied, becomes a permanent condition, carrying them laughing through periods that would try even a Jesuit's soul and worry him so that—as the Indians warn—he could become sick:

I saw them, in their hardships and in their labors, suffer with cheerfulness. ... I found myself, with them, threatened with great suffering; they said to me, "We shall be sometimes two days, sometimes three, without eating, for lack of food; take courage, Chihine, let thy soul be strong to endure suffering and hardship; keep thyself from being sad, otherwise thou wilt be sick; see how we do not cease to laugh, although we have little to eat" (LeJeune, 1897, p. 283; cf. Needham, 1954, p. 230).

Date: 2014-12-21; view: 1296

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| At least to the time Lucretius was writing (Harris, 1968, pp. 26-27). | | | Rethinking Hunters and Gatherers |