CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Michael McIntyre - Life And Laughing. My StoryPenguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published 2010

Copyright © Michael McIntyre, 2010

All images courtesy of the author except: FremantleMedia (Michael’s father with Kenny Everett and Barry Cryer); © The Sun and 01.06.1984 / nisyndication.com (Newspaper clipping of Michael’s mother with Kenny Everett); Richard Young / Rex Features (Michael with his wife at the GQ Awards); Dave M. Benett / Getty Images (Michael with Ronnie Corbett, Rob Brydon and Billy Connolly); Ken McKay / Rex Features (Michael with Prince Charles); Ellis O’Brien (DVD advert at Piccadilly Circus, Michael on stage at the Comedy Roadshow, Michael on stage at Wembley)

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-141-96971-8

For Kitty, Lucas and Oscar

Table of Contents Chapter 1Chapter 2Chapter 3Chapter 4Chapter 5Chapter 6Chapter 7Chapter 8Chapter 9Chapter 10Chapter 11Chapter 12Chapter 13Chapter 14Chapter 15Chapter 16Chapter 17Chapter 18Chapter 19Chapter 20Chapter 21Chapter 22Chapter 23Chapter 24Chapter 25

I am writing this on my new 27-inch iMac. I have ditched my PC and gone Mac. I was PC for years, but Microsoft Word kept criticizing my grammar, and I think it started to affect my self-esteem. It had a lot of issues with a lot of my sentences, and after years of its making me feel stupid I ended the relationship and bought a Mac. It’s gorgeous and enormous, and I bought it especially to write my book (the one you’re reading now). For the last six months, I’ve been looking to create the perfect writing environment. Aside from the computer, I have a new desk, a new chair and a new office with newly painted walls in my new house.

When my wife and I were looking at houses, she would be busily opening and closing cupboards and chattering about storage (after a few months of house-hunting, I became convinced my wife’s dream home would be the Big Yellow Storage Company), and I would be searching for the room to write my book. The view seemed very important. Previously, views hadn’t been that important to me. I prefer TV. Views only really have one channel. But suddenly I was very keen to find a room with a view to inspire me to write a classic autobiography. Like David Niven’s, but about my life and not his.

The house we fell in love with had a room with a beautiful view of the garden and even a balcony for closer viewing of the view of the garden. It was a room with a view. It was perfect. I could create magic in this room. Soon after moving in, I plonked my desk directly in front of the balcony window. I stood behind the desk drinking in the view of my garden and thought, ‘I need a new chair’, a throne of creativity. With this view and the right chair, I can’t possibly fail.

The big question when office chair purchasing is ‘to swivel or not to swivel?’ I would love to find out how many of the great literary works of the twentieth century have been written by swivelling writers. Were D. H. Lawrence, J. R. R. Tolkein or Virginia Woolf slightly dizzy when they penned their finest works? I tried out several swivel chairs in Habitat on the Finchley Road for so long that I got told off. I realized a swivel chair would be a mistake. I’d have too much fun. I might as well put a slide, a seesaw or a bouncy castle in my office. So I settled on a chair whose biggest selling feature was that you can sit on it.

With my chair, desk and view sorted, it was time to address the décor. The previous owner had painted the walls of my new office orange. I’ll try to be more specific. They were Tangerine. No, they were more a Clementine or maybe a Mandarin. Come to think of it, they were Satsuma. Now, there was no way on God’s earth I could write this book with a Satsuma backdrop, so I went to Farrow & Ball on Hampstead’s high street. Farrow & Ball is the latest in a long line of successful high street double acts (Marks & Spencer, Dolce & Gabbana, Bang & Olufsen). It’s basically paint for posh people. I don’t know who Farrow was, or indeed Ball, but I bet they were posh. Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe Ball is Bobby Ball from Cannon and Ball, who tried his luck in the paint industry encouraged by Cannon’s success manufacturing cameras.

I perused the colour chart in Farrow & Ball. There are so many colours, it makes you go a bit mad trying to decide. It’s also very hard to distinguish between many of them. A quick googling of the Farrow & Ball colour chart reveals ten different shades of white. All White, Strong White, House White, New White, White Tie … you get the idea. I once bought a white sofa from DFS. It was white. If you asked a hundred people what colour it was, I would say that a hundred of them would say it was white. In actual fact, they would all be wrong; it was Montana Ice. I would suggest that even if you asked a hundred Montanans during a particularly cold winter what colour it was, they would say, ‘White.’

After a brief discussion with my wife (she’s actually colour blind, but I find it hard to reach decisions on my own), I popped for the unmistakable colour of Brinja No. 222. A slightly less pretentious description would be aubergine. Most people call it purple.

My surroundings were now nearly complete: new desk, new chair, lovely view and Brinja No. 222 walls. I placed my Mac on the desk and lovingly peeled off the see-through plastic that protects the screen, took a deep breath and sat down. Unfortunately 27 inches of screen meant that my view was completely obscured. Panic. Why didn’t I think of that? The whole window was blocked by this enormous piece of technology. I was forced to move the desk to the opposite wall. I now had a face full of Brinja No. 222 and my back to the view. I would have to turn the chair around at regular intervals to be inspired by my view. I should have bought the swivel chair.

OK, I’m ready. I’m ready to start my book. It’s an autobiography, although I prefer the word ‘memoirs’. I think it’s from the French for ‘memories’, and that pretty much sums up what this book is going to be. A book about my French memories. No, it’s basically everything I can remember from my life. The bad news is that I don’t have a particularly good memory. You know when someone asks you what you did yesterday, and it takes you ages to remember even though it was just one day ago – ‘I can’t believe this, it was just yesterday’, you’ll say before finally remembering. Well, I’m like that, except sometimes it never comes to me. I never remember what I did yesterday. Come to think of it, what did I do yesterday?

‘Memoirs’ just sounds a lot sexier than ‘autobiography’. Not all words are better in French. ‘Swimming pool’ in French is piscine, which obviously sounds like ‘piss in’. ‘Do you piscine the piscine?’ was as funny as French lessons at school ever got for me. Only writing BOOB on a calculator using 8008 in Maths seemed funnier. We’ve borrowed loads of French words to spice up the English language: fiancé, encore, cul-de-sac, apéritif, chauffeur, pied-à-terre, déjà vu. In fact, you could probably speak an entire English sentence with more French in it than English. ‘I’m having apéritifs and hors d’oeuvres at my pied-à-terre in a cul-de-sac. After some mangetouts, I’m sending the kids to the crèche and having a ménage à trois with my fiancée and the au pair.’ Sounds like a great night.

The good news is I think there’s more than enough in my patchy memory for the book. Whatever the French for ‘patchy memories’ is, that’s what this book is. So where better to start than with my earliest memory? I was at a pre-school called Stepping Stones in North London in a class called the Dolphins. I must have been about four years old. I remember it being some kind of music group. We were all in a circle with instruments. I may have had a xylophone, but I can’t be sure. What I do remember is that there was the distinct smell of shit in the room. At this age kids are toilet-trained, so whereas only a couple years previously at nursery or playgroup the smell of shit was a given, in this environment it was unwelcome.

The simple fact was, a four-year-old kid had taken a shit in his or her little pants. It wasn’t me. I have never pooed my pants, although as this was my earliest memory, I can’t be sure. I remember trying to ignore the smell of shit and just get on with what I was doing, much like being on the top deck of a night bus.

‘I smell poo,’ said the teacher. Cue hysterical giggling. ‘Please tell me if you think it might be you. You’re not in trouble.’

Nobody responded. A chubby boy holding a triangle looked slightly guilty to me. A blonde girl with a bongo also looked a bit sheepish.

The teacher enquired again. No response. A third time she asked. You could cut the pungent atmosphere with some safety scissors.

Still nobody came clean about their dirty little secret. Then the teacher announced something that I think is the reason I remember this moment still to this day. She said that if nobody would own up, then everyone must, in turn, pull their pants down to prove it.

Horror. I couldn’t believe this. How humiliating. In fact the thought of it nearly made me shit myself. A Chinese kid gasped and dropped his tambourine. One by one, around the circle, we had to stand up and reveal our bottoms to the music group. The tension may have damaged me for life. I remember this unbearable swelling of fear as my turn approached. I frantically scanned the room for the crapping culprit. I ruled out the teacher, although I had my doubts about the elderly woman on the piano. I pinned my hopes on this kid who had a permanently solidified snotty nose. I think everyone can recall the kid in their class at pre-school with a permanently solidified snotty nose. Well, my class had one. He was about four kids to my right, and I prayed it wasn’t just the nose area he’d let himself down in.

My prime suspect stood up, seemingly in slow motion, and burst into tears. It WAS him! Thank God. I was saved, but the experience has been permanently etched on my mind. Incidentally, if you were in that circle and were one of the kids who had to pull their pants down, please get in touch. I’d love to know how your life turned out.

It is odd how we remember scenes from our childhood at random. Your first few years are, of course, a total blank. I’ve got two sons, who are four years and one year old, and they aren’t going to remember any of their lives so far. I was going to take them to a museum today. Why bother? I might just send them to their rooms until they’re old enough to remember some of this effort I’m putting in.

So everything prior to Poo-gate is a mystery to me. I have to rely on my parents, old photographs and Wikipedia to fill me in. According to Wikipedia, I was born in 1976 on 15 February. However, according to my mother, it was 21 February 1976. I don’t know who to believe. One thing they both agree on is that I was born in Merton. I think that’s in South London. I’m flabbergasted by this news as I am a North Londoner through and through. My opinion about South London is exactly the same as the opinion of South Londoners towards North London: ‘How can you live there? It’s weird.’ I get a chill when I drive over Hammersmith Bridge. I feel as though I’m entering a different world. I wonder if I need a passport and check that my mobile phone still has a signal. The roads seem to be too wide, they don’t have parks, they have ‘commons’, and everyone looks a bit like Tim Henman’s dad.

(I’ve just realized that I have to be careful about how much personal information I reveal. I think there’s already enough to answer most of the security questions at my bank and get access to all my accounts.)

I have details about my birth from my mother, who says she was there for most of it. I weighed 8 pounds and 11 ounces. I’m telling you that because the weight of babies seems very important to people. No other measurement is of interest: height, width, circumference – couldn’t give a shit. But the weight is must-have information.

I was a big baby. My mother tells me this, and so does everyone else when they learn of my opening weight. Like it was my fault, I let myself go, I could have done with losing a few ounces, a little less ‘womb service’ and a little more swimming and maybe those newborn nappies wouldn’t have been so tight.

Not only was I a big baby, I was also remarkably oriental in appearance. Nobody really knows why I looked like Mr Miyagi from The Karate Kid and, let’s be honest, my appearance has been the source of quite a lot of material for me. A midwife asked my mother if my father was Chinese or Japanese. My grandparents thought my parents took home the wrong baby. Questions were asked about my mother’s fidelity. My father beat up our local dry cleaner, Mr Wu.

My mother wondering whether she’d accidentally picked up a Super Mario Brother from the hospital.

Every year I, like you, celebrate my own birth and the fact that I am still alive on my birthday. This is always a very emotional day for my mother, who annually telephones me throughout the day reliving my birth. She calls without fail at about 3 a.m. telling me that this is when her waters broke, and I get phoned throughout the morning and afternoon with her updating me on how far apart her contractions were. At 5.34 p.m., I get my final phone call announcing my birth, and then she reminds me that I was ‘8 pounds 11 ounces, a very big baby’.

Since I became a comedian, she now adds that the labour ward was also the scene of my very first joke. Apparently, when I was only a few minutes old, the doctor lay me down to give me a quick examination, and I promptly peed all over him. I’m told it got a big laugh from the small audience that included my mother, father, the midwife and the doctor. Knowing me, I probably laughed too.

It was the first laugh I ever got.

Why do I look foreign? Let’s examine my heritage. My parents are not English people. My father is from Montreal in Canada, and both my mother’s parents were from Hungary. I am therefore a ‘Canary’. I consider myself British. I have only visited Hungary and Canada once.

My one and only visit to Hungary was with my grandmother and my sister Lucy. I was twenty years old, Lucy was eighteen and my grandma was seventy-nine. My grandmother was an eccentric woman, to say the least. Think Zsa Zsa Gabor or Ivana Trump, and you wouldn’t be too far out. She was funny, glamorous and rich. A true character. I will do my best to convey her accent when I quote her.

‘Helllow, daaarling’, that kind of thing.

This is actually how she wrote English as well as spoke it. Born in Budapest, she claims to have ‘rrun avay vith the circuss’ as a child before marrying scientist Laszlo Katz. When the Nazis showed up in 1939, they fled their home country and settled in Roehampton, South London (I would have taken my chances with the Nazis). They lived in a Tudor house. You know, white with black beams. Well, according to my mother, my grandma painted the black beams bright blue until the council made her paint them black again three weeks later. She didn’t speak a word of English when she arrived and learned it from eavesdropping and watching television, much like E.T. or Daryl Hannah in Splash.

‘Hellooo Daaarlings!’ My glamour Gran.

My grandmother was undoubtedly a bright cookie, and her vocabulary soon increased enough for her to get by. However, her accent would still hold her back. Trying to buy haddock at her local fishmonger’s, she would ask politely, ‘Do you hev a heddek?’

Unfortunately, the fishmonger thought she was saying, ‘Do you have a headache?’

‘No, I’m fine, thank you, love,’ he would reply. He thought she was a nutty foreign lady enquiring after his well-being. He was only half right.

The headache/haddock misunderstanding occurred several times until my grandmother burst into tears in her blue Tudor house. She asked her husband through her sobs, ‘Vot iz it vith dis cuntry, vy vont dey give me a heddek?’

My grandfather, whose accent was no better, stormed round to the fishmonger’s. He called the fishmonger a racist and demanded to know why he didn’t give his wife a ‘headache’ when there were several ‘headaches’ in the window. Luckily, the mistake was realized before they came to blows, which would have resulted in one of them having a genuine ‘heddek’.

My grandmother soon became fluent in English, so much so that she became quite the best Scrabble player I’ve ever encountered. She was even better than the ‘Difficult’ setting on the Scrabble App for my iPhone and would repeatedly beat her second husband, Jim, a Cambridge-educated Englishman. She was not only a tremendously talented Scrabbler, but also fiercely competitive and uncharacteristically arrogant when involved in a game, often calling me a ‘loozer’ or claiming she was going to give me a good ‘vipping’ or exclaiming, ‘Yuv got nothing, English boy!’

I enjoyed countless games of Scrabble with her in my late teens and early twenties. Not only did I enjoy the games, but there were serious financial rewards. You see, the Cambridge-educated Englishman was loaded, having made a fortune as a stockbroker. After his untimely death, my glamour gran was left to fend for herself. So I would visit her, and we would play Scrabble. If I won, she would give me a crisp £50 note, and if I lost, she would give me a crisp £50 note. So you see how this was quite an attractive proposition for a poor student. A lot of my friends were working as waiters and in telesales to make extra money, whereas I was playing Scrabble with my grandma at least five times a week.

You might wonder where these £50 notes were coming from. Well, my glamour gran didn’t really trust banks, so when her husband died, she withdrew a lot of money and kept it hidden around her lavish apartment in Putney. I’d open a cupboard in the kitchen looking for a mug and find one at the back packed with fifties. I once found 400 quid in a flannel next to the bath and two squashed fifties when I changed the batteries in her TV remote control.

K5 E1 R1 R1 I1 T1 Z10

‘Triple vurd score and “E” is on a duble letteer, so that’s sixty-six points. Read it a veep, loozer,’ said my grandmother in a particularly competitive mood as she stretched her lead.

Now, although she was a wonderfully gifted wordsmith in her second language, she never learned how to spell many of the words. Often she would get a word that bore no resemblance to the one she was attempting. The best of which was undoubtedly ‘Kerritz’. It was a sensational Scrabble word. To use the Z and K on a triple letter score and score sixty-six – exceptional. The only problem was that outside of her mind the word was fictitious. It soon transpired that only the two Rs were correct and that the actual word she was attempting was ‘carrots’. I must have laughed for about half an hour.

If I’m honest, I’ve never really been that into history, neither of the world nor of my ancestors. I hadn’t asked many questions about my Hungarian ancestry, and I suppose I must have tuned out if it was ever mentioned prior to my Budapest trip. But the time had come. My grandmother, sister and I were off to half my family’s homeland. Astonishingly, nobody had mentioned to me or my sister that we still had family in Hungary; nor did they mention that they were Jewish.

So when we were met at Budapest airport by a man resembling a stocky Jesus Christ, I assumed he was the cab driver. When he kissed me and my sister all over our faces, I assumed he was quite the friendliest cab driver I had ever encountered. When Grandma told us he wasn’t the cab driver, I thought for a fleeting moment it was Jesus.

‘Heelloo, I im yur Unkal Peeeteer.’ His accent was worse than my grandmother’s.

It turned out Uncle Peter was the son of my real grandfather’s sister, my real grandfather being Laszlo Katz, the Hungarian scientist, and not Jim, the rich English stockbroker who was my grandmother’s second husband and the man who enabled us to afford the Hyatt Regency Hotel, Budapest. Are you following this? I’m not and couldn’t at the time.

Uncle Peter was Jewish. There was no mistaking that. He had the hair and beard of the Messiah and a trait that is stereotypically shared by Jewish men. He had a nose nearly the size of the plane we’d just got off. I didn’t know I had Jewish blood; I always thought that my grandfather was Catholic. In fact, he was. He changed his faith, as Judaism wasn’t all that trendy circa 1940. But nobody told me.

Suddenly I’m Jewish. I instantly started to feel more neurotic and speak with the rhythm of Jackie Mason. I turned to my grandmother, ‘Oy vey, why did you not tell me already? I thought I was Gentile, but I have Jewish blood pumping through my veins. Did you not have the chutzpah to tell me? Did you think I was such a klutz I couldn’t cope with it? You wait till we schlep all the way over here, treating me like a nebbish. This is all too much, I have a headache.’

‘Vy have you bought a heddek? Did yu not eat enuf on de plane that you need to smuggel fish? And we just valked through “Nuuthing to declare”!’

Uncle Peter was so pleased to see Lucy and me that it became quite emotional. His mother, Auntie Yoli, and he were the last remaining family in Hungary after the horrors of the war. By Hungarian standards, Peter had done very well for himself. I can’t remember exactly what he did, but I know there was a factory involved. He spoke good English and had love in his eyes. But looking at him, I could not help but wonder how I could possibly be related to the man.

In the car park we approached his 4x4. It was by far the most luxurious car on display. ‘Shtopp!’ hollered Peter, much like the man from the Grolsch adverts. He then took out his keys, pointed a device through the window and waited for a beep. ‘It is now safe to enter.’ Safe? What was he talking about? ‘You must vait for mi to disingage the sacurrity system,’ he continued, ‘othurwide, verrrryy dangeruss.’

‘Isn’t it just an alarm?’ I asked.

‘No, iiit iz gas.’

‘Gas? What do you mean?’

‘In Hungarry is verrry meny criimes. So if break in my caar, you get gas in fece, verry bed burning in eyes. Blind for meny minnuts,’ he said, quite matter of fact.

‘You can gas burglars in the face here? What happens if you forget to disengage it and open the car door?’

‘I have bin in hosspitaal three times!’

It turned out he had forgotten to turn off his car security system and, on three occasions gassed himself in the face. Each time he was hospitalized. In fact one time, while he was rolling around on the pavement in agony holding his eyes and screaming, somebody had casually taken his keys and nicked his stereo.

It was on hearing this that I was convinced. We are related.

I spent three days learning a lot about Budapest and my family. Unfortunately, the only thing I really remember is Peter gassing himself in the face – oh, and that he had green leather sofas. Hideous. Maybe the self-gassing affected his sight.

I have been to Montreal, my father’s birthplace, only once. As has been reported at length in every Daily Mail interview I’ve done, my father died when I was seventeen years old. I recently did interviews with the Daily Mail and Heat magazine back to back in a hotel in Manchester. The Mail grilled me at length about the passing of my dad until I had tears in my eyes. The interview ended, the tape recorder stopped, my tears were wiped, and the Mail journalist was replaced by the one from Heat, whose first question was ‘How do you get your hair so bouncy?’, at which point my publicist jumped in: ‘Michael doesn’t want to answer any personal questions.’

I was in Montreal for the Comedy Festival a few years ago. Montreal is split into French- and English-speakers, and as you can imagine, they don’t really get on. My first introduction to French in Montreal was an unfortunate incident in my hotel shower. When the letter ‘C’ is on a tap, I normally feel pretty confident I’m reaching for the ‘Cold’ tap. However, ‘C’ on French taps stands for ‘Chaud’ which means ‘Hot’. I turned up the ‘Chaud’, thinking it was ‘Cold’. When the water got hotter, I simply added more ‘Chaud’. I was scalded.

This wasn’t the only Anglo-French misunderstanding I encountered in Canada. When businessmen are on the road, often the only highlight is watching pornography in hotel rooms. Sad but true. In fact, checking out of a hotel can feel a bit like confession. ‘Forgive me, Novotel Leeds receptionist, for I have sinned; I watched four pornos. I also had two Toblerones, the Maltesers, the sour cream and chive Pringles and five miniature Cognacs from the mini-bar. And I have one of your towels in my bag.’

Checking in to my Montreal hotel, I had a few hours to kill until the gig so, and I apologize to younger readers, I was contemplating the potentially higher calibre of Canadian ‘adult’ entertainment awaiting me in room 417. The receptionist handed me the key for my room and then enquired whether it was the only key I required.

‘Do you want one key?’ she asked. However, in her thick French accent this became ‘Do you want wanky?’ I was startled to say the least. What kind of a hotel was this? I immediately went to my room for a cold shower, but as you know scalded myself.

Being in Montreal, I naturally felt nostalgic for my dad, but, unlike my trip to Hungary, I was alone. I sent an email to my father’s brother, Hazen. The last I had heard from him was that he was playing a cross-dresser in a Chinese sitcom (my family have had varying degrees of success in showbusiness). In the last twenty years, I had had lunch with him once, when he visited London. It was eerie as he shared mannerisms with my father, as well as his accent and intonations.

Hazen had remarried, to a seemingly sweet Chinese lady who smiled politely through lunch as Hazen reminisced about my dad. He literally didn’t stop talking while his spaghetti meatballs went cold in Café Pasta just off Oxford Street. His wife never spoke. ‘In all the years we’ve been married, she’s only ever said thirty-seven words to me. Two of them were “I do.’’’ He was funny. He spoke about my father’s dry sense of humour and how in the early sixties my dad had come to London as a comedian in search of stardom. And here I was, back in his native Montreal doing the same thing.

In his email, Hazen told me about the neighbourhood where he and my dad grew up in the fifties and places they used to go as kids. In particular, he mentioned my dad’s favourite deli. I searched for the neighbourhood and the deli on a map given to me by the concierge. Having located the deli, I was all set to go when I had second thoughts about my sentimental sojourn. I imagined a bustling deli full of lunching Canadians and wondered what I would gain by eating a pastrami sandwich on my own among them. The fact is, my dad wasn’t going to be there.

But he lived on in me and he also lived on in his other kids. Aside from my sister Lucy, my dad had two further children after my parents divorced, Billy and Georgina, both of whom I had had very little contact with since my father died. So I found them on Myspace (my computer just underlined Myspace in red and suggested I meant Facebook. Apple iMacs are so cool) and sent messages.

Within hours they both got back to me. Billy, it transpired, was in Vermont for the summer. A mere three hours’ drive. A few hours later, there was a knock on my hotel room door and standing there was my father’s son, Billy McIntyre. Billy was an all-American kid. He was twenty years old, the lead singer in a band and good-looking. In short, nothing like me. We shared a special few days together that I’m sure would have meant more to our dad than me sitting alone in his favourite deli.

I was in Montreal primarily to work, so Billy came with me to a number of my shows. I introduced him to my fellow comedians as ‘my long-lost brother’, not realizing that this seemed dubious to say the least. It soon got back to me that the word was I was a homosexual. It looked for all the world as if I had picked up a local rent boy. It never crossed my mind how strange it seemed that I was suddenly hanging around with this young American kid who was also sleeping in my room.

All of the comedians were staying in the same hotel. Billy and I would walk past a gaggle of gagsters who would stop their conversation and stare, muttering to each other about the shameless exhibiting of my new sexual direction. To me, it was an emotional reunion; to everybody else, it was like a gay version of the film Pretty Woman.

On my last day of the Festival, I was in the lobby saying goodbye to Billy and slipped him a few hundred quid. It was the big brotherly thing to do, but at this very moment Frank Skinner walked past and gave me a knowing nod. I must admit; it didn’t look good.

Now, older readers all remember the year of my birth. Not because my entering the world made international news headlines:

CHINESE TAKEAWAY!

BRITISH PARENTS TAKE HOME

ORIENTAL BABY

It’s because 1976 was the last baking hot summer. It has become a legendary year, referenced by middle-aged Brits every time there is a heat wave (two hot days in a row), a mini-heat wave (one hot day in a row) or a micro-heat wave (the sun comes out between two clouds). This just winds me up as every spring I, like you, yearn for a long hot summer that never materializes. Well, it turns out I was actually alive for the best summer of them all. London was scorching and everyone was brown (although I was yellow due to jaundice). It was my first experience of weather and it was fantastic. I thought I lived in California, my mother didn’t need to buy me clothes for eight months, my first word was ‘Nivea’.

Me, during my brief stint as an East End Crime Lord.

In truth, the heat wave of 1976 was probably greatly exaggerated. In future years when we talk about the winter we’ve just endured, we’ll probably add a few inches of snow and deduct a few degrees from the temperature and the wind chill factor. When our grandchildren are longing for snow, we will wax lyrical about the snow of 2010 (of course, when I am a grandparent, I will then look almost exactly like Mr Miyagi so I will ‘Wax lyrical ON, Wax lyrical OFF’ about the snow of 2010… This joke requires the viewing of The Karate Kid, the original film starring Ralph Macchio.):

‘The blizzard lasted six long weeks. Sixteen feet of snow fell solidly. They were using a blank white sheet of paper for the weather forecast. Cars, houses, entire villages, disappeared. The whole country was housebound apart from Torvill and Dean, and Omar Sharif, who had experienced similar conditions during his portrayal of Dr Zhivago.’

I think Sharif would also have coped well in the heat wave of 1976, thanks to his sterling work on Lawrence of Arabia. Anyway, this isn’t Omar Sharif’s autobiography, it’s mine, so let’s get back to it. I’m born, it’s hot, and I move into a tiny flat with my parents in Kensington Church Street, London. My birth certificate states that at the time my father was a ‘Record producer’. I know bits about his career in comedy, but little about his days in the music industry other than that he had one big hit, the novelty record ‘Grandad’ by Clive Dunn, which was number 1 for three weeks in 1971.

My mother, who has produced no novelty records about family members, was beautiful. I’m basing this on old photographs. In every one, she looks stunning, but let’s be honest, she would have weeded out any less than flattering photos over the years and destroyed them. This is what women do; they constantly edit their photo albums so that history may remember them looking their best. Old people basically get the best photo from their youth and use it as a sort of publicity shot – ‘Look at me, I could have been a model, I had an 18-inch waist, I got asked for ID at the pictures when I was thirty-two.’ That’s the great thing about being old – you can say what you like to your grandkids. Not only because they weren’t there, but also because they’re not really listening.

My mum, Kati Katz, a teenage pregnancy waiting to happen.

Personally, I am particularly un-photogenic. Cruelly, it is suggested that people who are not photogenic are ugly. I had some stand-up material along those lines about passport photos and how people hide them claiming, ‘It’s a terrible photo, I’m really ugly in it, I don’t look anything like this.’

If this was true, they wouldn’t get past immigration, but the fact is they do. The immigration guy never says, ‘You don’t look anything like this photo. This photo is of an ugly person. You, on the other hand, have a sculpted beauty that brings to mind a young Brando. I will not let you into this country, you gorgeous liar.’ No, they look at your ugly photo and then look at your ugly face and let you go to baggage reclaim.

I’ve been lucky enough to be photographed by some seasoned snappers, but it is very difficult to get a good shot of me. I would say that I am happy with about 1 in 10 photos of me. I would say that my wife is happy with maybe 4 in 10 photos of her. Therefore the odds of getting a good photo of us together are 0.4 in 10 (I wasn’t just reading the word ‘BOOB’ on my calculator in Maths). To put it another way: very unlikely. The odds on a family photo where my wife, our two boys and I look good all at the same time: impossible. The result is that there are very few photos of my wife and me together that haven’t been deleted or destroyed by one of us.

To get a photo of my wife and me together, somebody else has to take it. On our honeymoon in the Maldives, we kept taking photos of each other; me in bed alone, her swimming alone, me in a hammock alone, her in a jacuzzi alone. The woman in Boots, Brent Cross, developing our holiday snaps must have thought we’d each gone on an 18–30 singles holiday and not pulled. Who was I supposed to ask to take our photo? I’ve never really taken to asking waiters when you have to explain that your camera works in exactly the same way as every other camera on earth – ‘it’s the button on the right’ – and it still takes them so long to work it out that you develop a slightly annoyed smirk, ruining the photo.

Having no photos of us together on our honeymoon simply wouldn’t do. So on the last day when I had one photo remaining on our disposable camera, I asked a sweet gentleman called Nizoo who was delivering room service if he could take a photo. ‘Of course,’ he agreed, before standing up as straight as he could and smiling inanely at us. He was under the misapprehension that we wanted to photograph him. I didn’t have the heart to tell him that it was us I wanted him to photograph. The upshot is that the only couple who appear in my honeymoon photos are Nizoo and myself.

I imagine the woman in Boots, Brent Cross, sitting in the darkroom thinking, ‘Ah, sweet, he met someone right at the end.’

My mother may also have looked good in 1976 because she was nineteen years old. Yes, I am the result of a teenage pregnancy. My father, on the other hand, was thirty-seven. He was a cradle snatcher, which was good for me as I was now sleeping in the vacated cradle. Thirty-seven! That’s four years older than I am now, and I’m writing my autobiography. He had a whole life before me. Born, as you know, in Montreal, he was named Thomas Cameron McIntyre, but changed his name to Ray Cameron to make this book slightly more confusing. Ray Cameron was his stage name. My mum called him Cameron, showbiz associates called him Ray, his mother called him Tommy and I called him Dad.

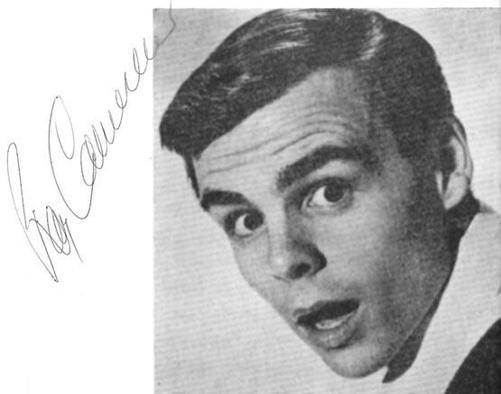

An early publicity shot of new Canadian comedian Ray Cameron, my dad.

He decided that he’d have a better shot at fame and fortune with a new name. Loads of celebs have changed their name. In most cases I think artists would have found the same success with their original names: Elton John (Reginald Dwight), Cliff Richard (Harry Webb), Kenny Everett (Maurice Cole), Michael Caine (Maurice Micklewhite), Tina Turner (Anna Bullock), Omar Sharif (Michael Shalhoub – I’m obsessed with him today), Meatloaf (Steak Sandwich – I made this one up). In some cases, however, you can see why a change was necessary. Would you have been comfortable listening to ‘Wonderful Tonight’ by Eric Clapp? Laughing at Fawlty Towers with John Cheese? Or watching Newsnight with Jeremy Fuxmen (I made this one up, too)?

According to his brother Hazen, when we chatted in Café Pasta, the young Thomas McIntyre originally wanted to be a singer, but suffered a serious throat infection (I don’t remember the details) in his teens. He lost his voice for months, communicating by writing things down. Apparently he already had a wonderfully dry sense of humour, but his time spent voiceless meant he couldn’t waste any words when communicating through notes. This sharpened his comedy mind, and he often presented notes that had surrounding Canadian people in stitches. When he could speak again, his singing voice was lost, but his comedy voice was found. He started to perform stand-up locally with success before crossing the pond to try his luck in the bright lights of London. This might be a romanticized version of events, but I like it, so I’m going with it.

In the early Swinging Sixties, my father, who was in his early swinging twenties, was performing live comedy in swinging London. The sixties stand-up scene was very different to what it is today. There were no comedy clubs. This was the age of cabaret and variety. My dad was the MC, introducing dancing girls and novelty acts while telling jokes in between. I feel extremely lucky to have some of his actual scripts. Only one of them, dated 11 November 1962, mentions a venue, the nightclub Whiskey a Go Go. I researched it thoroughly (typed it into Google) and it seems to have been the original name of the Wag Club in Wardour Street and is described as a ‘late-night dive bar’. The office for Open Mike Productions, who make Live at the Apollo and Michael McIntyre’s Comedy Roadshow, is just a few doors down Wardour Street. In the last few years, I have spent countless days working there.

In fact, I’ve probably spent more time than I should have at the Wardour Street office. This is mainly due to Itsu, the sushi restaurant at number 103. I’m a big fan of raw fish. Although Itsu itself is synonymous with poisoning Russian spies with Polonium-210, the sushi that doesn’t contain radiation is divine, particularly the scallops. Itsu has one of those carousels, where you sit down and the food just passes by you: salmon, tuna, squid, miso soup, edamame beans. I once saw a Samsonite holdall around the time Terminal 5 opened at Heathrow. You pick what you want from colour-coded plates that relate to their price, and I literally cannot stop eating. My rule is that once the plates are piled up so high that I cannot see the carousel, I should probably get the bill.

I’m glad there isn’t an Itsu closer to home. You know the expression ‘There are plenty more fish in the sea’? Well, I don’t think that’s the case any more. What I don’t understand about the Russian spy murderers is, how did they know he was going to pick the Polonium-poisoned piece from the carousel? Maybe they just wanted to kill somebody at random. Like Russian roulette, they poisoned one piece of sushi and watched it go round and round the carousel waiting for one unlucky luncher to select it. It could have been some advertising exec but ended up being a Russian spy. I don’t know. What I do know is that it’s a bloody cheek having 12.5 per cent service included in the bill. I picked the dishes off the carousel and brought them to my table. The waiter only takes them away. I figure this is worth a maximum of 6 per cent.

It’s incredible to think that as I sit in Itsu arguing over the service charge in front of a tower of empty plates resembling the Burj Khalifa building in Dubai, fifty years earlier my dad was performing just a few yards away, clutching these very notes I have in my hand today.

It’s fascinating for me to see my dad’s notes. A comedian’s notes tend to make little sense. They will consist of subject headings and key words. My dad’s notes say things like ‘Westminster Abbey’, ‘School teacher’, ‘The house bit’ and ‘Your horse has diabetes …’ Comedians carry around these scribbles of key words that they hope contain the DNA of a good gag. Looking at some of the notes from my last tour, it’s the same kind of thing: ‘Wrinkle cream’, ‘Morning’, ‘Last day sunbathing’. I once thought it would be fun to swap notes with other comics on the bill and try to make jokes about each other’s subjects onstage. This suggestion wasn’t met with much enthusiasm in Jongleurs, Leeds, circa 2005.

In among the notes there is a script, and it’s hilarious. So here’s my dad in a Soho nightclub in 1962:

I’d like to tell you a bit about myself … I’m one of the better lower priced performers … I’m from Canada. I realize that it may be a little difficult because you’ve never heard of me here but don’t let it worry you ’cause I have the same problem in Canada …But it’s real nice to be here … I brought my wife over with me … You know how it is … You always pack a few things you don’t need …We had a very interesting flight over here, we came on a non-scheduled airline … You know what that is? … That’s the type of airline who aren’t sure when the crash is going to be … You see, they use old planes … In fact this one was so old that the ‘No Smoking’ sign came on in Latin …But don’t get me wrong it wasn’t all bad … There were only a few things that I didn’t like … For instance when I fly I like to have … Two wings …It’s such a treat to have so many attractive ladies in the audience … Especially for me … Because I come from a very small town … And I don’t want to say the girls in my home town were ugly, but we had a beauty contest there once … And nobody won …They finally picked one girl and called her the winner, actually she wasn’t that bad … She had a beautiful bone structure in her face … Those eyes … Those lips … That tooth … She had this one tooth right in the front and it was three inches long … The first time I saw her I thought it was a cigarette and tried to light it … To see her eating spaghetti was really something … She used to put her tooth right in it and spin the plate … But I married her anyway …I got married because I wanted to have a family and it wasn’t long before we had the pitter-patter of tiny feet around the house … My mother-in-law’s a midget … I told her to treat the house as if it were her own … And she did. She sold it … I hope you found that as funny as I did. I particularly like the ‘I thought it was a cigarette and tried to light it’ bit. This is proper old-school stuff, wives and mother-in-laws being the butt of the joke. I don’t know if he wrote all of it, some of it or none of it. I know that comedians back in those days used to share jokes around a lot, but nevertheless it’s still funny. I have gags, I couldn’t really survive without punchlines, but a lot of my material is observational or mimicry. It’s a different approach to making people laugh – it makes me laugh, which is why I say it. But you can understand how ‘old-school’ comedians can be baffled by ‘alternative’ comedy, because there are so few proper ‘gags’. ‘Where are the jokes?’ they’ll say, normally in a northern accent. For me, it’s quite simple: if people are laughing, it’s comedy … or tickling.

Browsing my dad’s notes, I’m not sure he was the most confident performer. There are two pages entitled ‘No Laughs’, back-up in case the jokes weren’t working. Here are some of them:

Well, I wasn’t born here, but I’m certainly dying here.That gag is twenty years ahead of its time. It’s just your bad luck that you had to hear it tonight.Well, from now on, it’s a comeback.I don’t mind you going to sleep, but you could at least say goodnight. Ouch. I certainly never had a plan for dying onstage. I’ve always found that once you’ve lost an audience, there’s nothing you can do to win them back.

Comedians talk about stand-up in very hostile terms. If you have a good gig, you ‘killed’, and if you have a bad gig, you ‘died’. It’s kill or be killed. Witnessing a death onstage is excruciating. Experiencing it is indescribable. The worst death I ever saw was during my brief stint at Edinburgh University, years before I took to the stage myself. I never knew the comic’s name and haven’t seen him since. This career path was certainly evident that night, as he performed to near silence. It was a packed audience of about 400, including a gallery. The comedian was fighting for his life, sweating, dry mouth, throwing every joke he could think of at it. No response. People were turning away, chatting among themselves.

Now, I don’t know if it was thrown or dropped, but somehow a lit cigarette originating from the gallery landed on the comedian’s head. As it burned away atop his full head of hair, the audience started noticing the cigarette and giggling. Unaware of the lit cigarette, the comedian’s eyes lit up, too. ‘I’ve cracked them!’ he was thinking. He then started to loosen up, moisture flooded back into his throat, the sweat on his brow began to clear, and he confidently launched into more material. Flames started to plume from his head. The giggles now escalated into fully blown laughter. He thought he was Richard Pryor, but looked more like Michael Jackson making a Pepsi commercial.

‘You’re on fire, mate!’ someone shouted from the crowd.

He took this as a compliment.

‘Do you like impressions?’ he said, feeling like a star.

The audience were now weak from laughter, tears rolling down their student faces as he broke into his ‘Michael Crawford’, not realizing he was already doing a pretty good ‘Guy Fawkes’. It looked for all the world as though this ‘dying’ comedian might die for real. People were laughing so hard at the situation, they were unable to tell him he was ablaze, and he was so thrilled at the response to his ‘ooh Betty’ to notice. Eventually, just after he’d commented on the non-existent smoke machine, he ran from the stage screaming. It was a horror story and not for a moment was I thinking, ‘That’s what I want to do for a living.’

However bulletproof you think your ‘set’ is, a comic can die onstage at any time. From what I’ve been told, my dad didn’t need to use his ‘No Laughs’ jokes very often. He opened for the Rolling Stones and lived for a while with Irish comedian Dave Allen, who told my mum years later that my dad was extremely talented. But, unlike myself, I don’t think his vocation was to perform, and his move behind the camera began when he devised the comedy panel show Jokers Wild for Yorkshire Television. Hosted by Barry Cryer, the format was simple: Barry would give two teams of three comedians a subject to make a joke about. During the joke, a member of the other team could buzz in and finish it for points. It’s like Mock the Week but with flares, corduroy and more manners. The show was a hit and ran for eight series, regularly featuring Les Dawson, John Cleese (Cheese), Arthur Askey, Michael Aspel and my dad himself.

As indicated by my birth certificate, my dad was primarily involved in the music industry. It was during Jokers Wild that he met Clive Dunn and recorded ‘Grandad’. He and his partner Alan Hawkshaw (who signs his emails ‘Hawk’) were writing and recording songs. I met Alan when I was about thirteen. He’s a hilarious character. My dad, my sister and I went to his enormous house in Radlett, Hertfordshire. Music had been good to the Hawk, one piece of music in particular. He wrote a thirty-second tune that made him a fortune. Can you guess it?

Here’s a clue … It’s exactly thirty seconds long.

Here’s another … Du-du … Du-du … De-de-de-de … Boom!

Yes, that’s right, Countdown.

(I actually met Carol Vorderman once in a lift. I got in and she was standing at the numbers and asked me, ‘What floor?’ If I couldn’t make a joke in these circumstances, I’m in the wrong business. ‘One from the top and four from anywhere else, please, Carol.’)

Those thirty seconds netted the Hawk a fortune. His house had its own recording studio, swimming pool, snooker room. He gets paid every time it’s played, that’s every weekday at about 4.56 p.m. He actually gets paid by the second, so the longer it takes for people to guess the conundrum, the more money he makes. You can imagine him in the eighties, turning on the telly at 4.55 p.m., hoping the contestants can’t decipher the conundrum so that he can afford a better holiday.

Countdown aficionados (judging by the number of adverts they have for Tena Lady in the break, Countdown is mainly watched by women who pee in their pants) will know that if the contestant buzzes in to guess the conundrum, the clock stops. If they correctly identify the jumbled-up nine-letter word, the game is over. However, if they get it wrong, the clock restarts, which means more money for Alan. You can only imagine the excitement in the Hawk household, whooping and cheering when they guess incorrectly, wild applause, back-slapping and champagne corks popping when the tune reaches its ‘De-de-de-de … Boom’ climax.

My sister and I loved Alan as soon as we met him. He was a charming and personable man. Within moments of our arriving, he sat at his grand piano and dramatically played various TV themes he had written that we might recognize, including the original Grange Hill. It’s wonderful to see someone so proud of their work, and I have to say his rendition of Countdown was one of the most moving thirty seconds of my life. We drove for a pub lunch in his new Japanese sports car, in which he played all his own music, announcing, ‘I only ever listen to my own music in the car.’

As the pub was about ten minutes away, I remember thinking, ‘I’m glad he has an extensive canon of work – otherwise we’d have to listen to Countdown twenty times back to back.’

So Alan and my dad were writing music and producing records in the sixties and seventies. In 1975, my father found a song and was looking for a singer. This is basically record producing in its purest form. He held auditions in his small office off Trafalgar Square, and in walked my mum, a bleached-blonde beauty young enough to be his daughter. ‘If you can sing half as good as you look, we’re going to be rich,’ observed my dad.

She couldn’t. Her audition was appalling. If she was on The X-Factor, Louis would have said through his giggles, ‘I’m sorry, you look great, but I don’t think singing is for you’; Danni would have said, silently seething over how gorgeous Cheryl looks, ‘It was a bit out of tune’; Cheryl would have diplomatically said, ‘I think you’re luverly, but I think you’re a bit out of your depth singing, sorry, luv’; and Simon would have said, ‘I give up’, and then walked off set, immediately cancelling The X-Factor, American Idol and Britain’s Got Talent, retiring from showbusiness to become a recluse with nobody knowing his whereabouts, apart from Sinitta.

My father’s reaction was less drastic. One thing led to another and before you knew it, I was peeing on the doctor in a hospital in Merton in 1976, which probably came as a relief to the doctor as much as me due to the Sahara-like temperatures.

When my mum fell pregnant (an odd expression: ‘Wow, you’re pregnant, what happened?’ ‘I fell … on top of that man’) with my sister Lucy, we moved in search of more space. We found it in a ground floor flat in leafy Hampstead. I know what you’re thinking – Kensington? Hampstead? La-di-da. I know. There’s no denying I had a pretty decent start. This is primarily due to my grandma (‘Helloo, daaarling’) marrying Jim, the wealthy Scrabble-losing stockbroker.

I can only imagine my father’s face when he found out this beautiful nineteen-year-old had rich parents too. And you can only imagine my grandma and Jim’s faces when they found out their daughter was marrying a thirty-seven-year-old Canadian comedian who went by several different names and whose greatest success was producing Clive Dunn’s ‘Grandad’. The relationship between my dad and grandparents was uneasy, to say the least. My mother recalls how on their first meeting my dad addressed the thorny issue of their wealth, saying, ‘I’m a bit worried about your money.’

To which my grandmother replied, ‘Don’t vorry about it, you’re not gettiing it.’

Relations certainly weren’t improved when my dad sold their holiday home in Malta, which Grandma and Jim had put in my mother’s name for tax reasons. I tried to talk him out of it, but my vocabulary was limited to ‘Ma’, ‘Da’ and ‘Shums’ (my word for ‘shoes’). I threw up on his shoulder, but it had little impact. The Maltese house was sold, and the Hampstead flat bought with the proceeds.

My mother was expecting her second child. I wasn’t. I thought she’d let herself go. I didn’t know she was about to give birth to a rival. I was the centre of attention at home. I was used to having everything my own way. I was the main man. Then one day my mum suddenly lost a tremendous amount of weight and there was this baby stealing my limelight. ‘Isn’t she beautiful?’, ‘Can I hold her?’, ‘Look at those little hands’, ‘Adorable’, gushed friends and relatives.

‘Michael, do you want to say hello to your new little sister?’ my dad asked.

‘Keep that little bitch away from me,’ I tried to say, although all that came out was, ‘Ma, Da, Shums.’

It was a shock to have competition at home, but I had to see the positives of having a sibling and a growing family. Unfortunately, I couldn’t and decided to try to kill my sister instead. According to my mother, up until Lucy was about six months old, I made several attempts on her life. Much like a Mafia hit, I would win her and my parents’ trust before striking. I would gently stroke her cheek, before trying to suffocate her with her own frilly booties. I would sweetly comb her hair, and then bash her in the temple with the brush. I poisoned her rusks with red berries I found in the garden and tried to drown her so many times that we had to take separate baths.

I’m pleased to say I finally accepted my sister and together we got on with the business of growing up in the eighties. But, in truth, there was another child in the house. Our mum. To give you an idea of the age gap, my mum once sprained her ankle and my father rushed her to Casualty, where the doctor said, ‘If you would like to just pop your leg up on Daddy’s knee.’ This pissed my dad off so much he sent my mum straight to bed without a story.

In America, she would only have just been allowed to drink alcohol, but here she was raising two kids and learning on the job. It’s a job she did wonderfully well, with only the occasional hitch. For example, normally an adult would tell the kids to buckle up in the car, but nobody wore a seatbelt in my mum’s mustard-coloured Ford Capri. My sister and I would just bounce around in the back, occasionally clinging on to the front seats for survival. And remember, there were no speed bumps in those days. By the end of a journey, I would often end up in the front and my sister on the ledge in front of the back window with Bronski Beat playing at full volume.

Family cars containing young kids will always be untidy. However, this is usually confined to the back. Not my mum’s Capri. The Capri was filthy in both the children’s area and my mum’s area. Strewn all over the front of the car would be crisp packets, bits of old chewing gum, magazines (yes, she would read at the traffic lights), Coke cans, old lipsticks and cassettes with unwound tape hanging out of them.

Occasionally my mother would clean the car, by throwing things out of the window, in traffic. Once she threw so much litter out of the car at rush hour on the Finchley Road that my sister and I sat open-mouthed in amazement in the back. Literally, she chucked about four magazines into the street while Kajagoogoo blared out of her Blaupunkt stereo. Moments later somebody got out of their car, picked up my mum’s discarded debris, and threw it back into our car. Unperturbed, my mum promptly threw it out again. This continued all the way between St John’s Wood and Hampstead.

Once, when we went shopping on Hampstead High Street, my mother loaded the boot with groceries, put me in the back seat and drove off. A few miles later, she started to get a nagging feeling she’d forgotten something. PG Tips? Shake n’ Vac? Culture Club’s ‘Do You Really Want to Hurt Me?’ on 7-inch vinyl from Our Price? No, my sister Lucy, who was still in her pram on the pavement fifteen minutes later when we returned. ‘Why didn’t you say anything?’ my mother screamed, blaming me.

‘Hey, I’ve been trying to kill that bitch for months,’ I said, although this came out as ‘Ma, Da, Shums.’

After I moved to Tanta in Egypt with my Lebanese Catholic parents Joseph and Abia … (Oh no, I’ve slipped back into Omar Sharif’s autobiography. What’s wrong with me?)

In my teens, I fell ill (nothing serious, don’t worry) and checked in at the doctor’s surgery reception in Hendon. The receptionist handed me my medical notes and said, ‘Please give these to the doctor, and you’re not allowed to look at them.’

‘Of course not,’ I lied.

Moments later, out of sight, I had a flick through my little malady memoirs. I got quite nostalgic about my ‘pain in the abdominal area’ of March 1987, my ‘blurred vision’ of May 1985 and my ‘soreness in left ear’ of November 1983. What surprised me, however, were the first few entries. ‘Michael not talking. Parents worried.’ ‘Michael still not talking, just grunting. Parents increasingly concerned.’ ‘Michael only saying a few words. Worrying rate of development. Should be monitored. Only says “Ma”, “Da” and “Shums’’.’ I was shocked to find out that my early medical history was remarkably similar to Forrest Gump’s. Apparently my sister spoke before me despite being two years younger. Her first words were ‘Is Michael retarded?’

My younger son, Oscar, is nearly two and only has one word, ‘hoover’, which he calls ‘hooba’. Out of all the things in the world, why ‘hoover’? My oldest, Lucas, who is four and a half – his first word was ‘car’. I have no idea why, but I suppose you’ve got to start somewhere. Maybe they’ll go into business together one day and run ‘McIntyre Brothers’, a car valeting service.

So my memories really start to kick in at our Hampstead flat, which I remember to be quite dimly lit. Maybe at my parents’ height this was ‘mood lighting’, but from where my sister and I were crawling, it was just dark. The flat was in a big old Edwardian building that also contained three other flats.

The room I remember most is the living room. This is odd, because it’s the only room that my sister and I were strictly forbidden to enter. I became obsessed with the living room, presumably because it was out of bounds. The living room was darker than the rest of the house, with dark green sofas and lots of plants. Because I was only two foot tall, to me it was like an indoor night jungle with soft furnishings. ‘Don’t go in there, that’s Mummy and Daddy’s special room.’ Special room? What goes on in that mini-Jurassic Park of theirs?

My wife and I do the same today with our kids. We don’t let them in the living room because it’s our special room that we want to keep nice. I’m sure many people readi Date: 2015-01-11; view: 4826

|