CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Marital psychology

Happily ever after? Feb 2014 by N.L. | CHICAGO

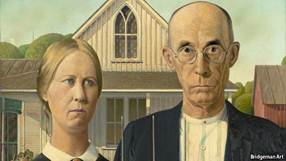

AT THE beginning of the film Sideways, Miles, a wine lover, is asked why he is so fond of pinot noir. He replies that the grape is difficult to grow: it is thin-skinned, temperamental and ripens early. It cannot thrive when neglected, needs constant care and attention, and only the most patient cultivators can coax it to reach its "fullest expression". This explanation matters to psychologists such as Eli Finkel at Northwestern University in Chicago because it is a perfect metaphor for the modern marriage. It needs nurture and attention. Dr Finkel told a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science this week that most married Americans expect their spouses to develop profound insights into the essential qualities of their other half, fulfilling their needs for esteem and self-actualisation. A spouse, these days, can be expected to be a confidant, lover, co-parent, breadwinner, activity partner and therapist. This, he concludes, makes being happily married harder than it was in the past. Consider America in the 1700s, where the basic unit of production was the farmhouse. In marriage people sought necessities: food production, shelter and safety. The notion of looking for love would have been "a little ludicrous" says Dr Finkel. Yet by the 1850s, with the spread of wage labourers, a "companion model" of marriage emerged, and with it romantic conceptions of the partnership. This idea remained dominant until the 1960s when the counter-cultural movement added new goals: to help individuals on their voyage of self-discovery and with their goal of becoming an ideal version of themselves. Such trends have unfolded somewhat similarly in other parts of the Western world. Although modern marriages now offer the promise of something far more fulfilling than a grunt from one's partner while tending the chicken coop, achieving this state of affairs has proven difficult for many. Because as the notion of what a marriage ought to be has grown, spouses are spending less time with each other. Those with children are devoting more time to parenting. Those without are working longer hours. Lack of money takes its toll too—there is a stark divergence in the marriage outcomes of relatively wealthy versus poor Americans. Rich people have resources to make their marriages work; romantic getaways and meals out perhaps do keep helping to seal the deal. Dr Finkel's intensive study of modern marriages has yielded suggestions for making them better. Some are pretty obvious, such as investing more time in one's marriage. Some are less so, such as expecting less of it. This might involve relying more on one's family or friends for emotional support, rather than expecting one person to fulfil many different roles. For example, it may not be realistic to expect a partner who is emotionally tone deaf to play the role of one's therapist. Other suggestions are less intuitive. One odd little marriage "hack" Dr Finkel says seems to help is for spouses to write for seven minutes every four months about a recent conflict in their marriage. They seek to reappraise the conflict from the perspective of a neutral third party. A two-year study involving 120 couples found that this simple intervention could eliminate the decline in marital quality that was seen in the control group. There are some radical ideas, too that involve changing one's expectations. Dr Finkel points out that many committed couples and spouses maintain separate living spaces. Another option is to find sex, or even love, elsewhere while remaining married. So-called "consensual nonmonogamy" is found in 4-5% of Americans. But if current theories in relationship science correctly imply that a core set of needs must be fulfilled by one person, finding love or sex elsewhere would be likely to backfire for many. A sobering thought on Valentine's Day. Ultimately, the key to a successful marriage is having the expectations of two people meet—whatever these expectations are. Many great writers and artists, for example, have found fulfilment in careers rather than marriages: Jane Austen and Michelangelo come to mind. That is not to say that the peak of marital satisfaction is a mountain not worth trying to climb. As Miles said of pinot noir done right, "oh its flavours, they're just the most haunting and brilliant and subtle and... ancient on the planet." Questions: 1) What is the divorce rate in your country? Why is it that high? 2) If it’s not the marriage what other forms coexisting could be possible in the society? (think of the history of mankind) 3) why was marriage important when it started to exist? 4) Do you think marriage is becoming less important now? Why/why not?

Date: 2015-01-11; view: 956

|