CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

I’m not sure how much violence and 9 page

‘True,’ said Calder. ‘You’ve been generosity itself. Oh. Apart from trying to kill me, of course.’

Dow’s forehead wrinkled. ‘Eh?’

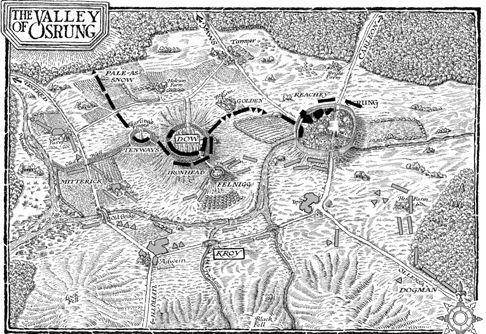

‘Four nights past, at Caul Reachey’s weapontake? Bringing anything back? No? Three men tried to murder me, and when I put one to the question he dropped Brodd Tenways’ name. And everyone knows Brodd Tenways wouldn’t do a thing without your say-so. You denying it?’

‘I am, in fact.’ Dow looked over at Tenways and he gave a little shake of his rashy head. ‘And Tenways too. Might be he’s lying, and has his own reasons, but I can tell you one thing for a fact – any man here can tell I had no part in it.’

‘How’s that?’

Dow leaned forwards. ‘You’re still fucking breathing, boy. You think if I’d a mind to kill you there’s a man could stop me?’ Calder narrowed his eyes. He had to admit there was something to that argument. He looked for Reachey, but the old warrior was steadfastly looking elsewhere.

‘But it don’t much matter who didn’t die yesterday,’ said Dow. ‘I can tell you who’ll die tomorrow.’ Silence stretched out, and never had the word to end it been so horribly clear. ‘You.’ Seemed like everyone was smiling. Everyone except Calder, and Craw, and maybe Caul Shivers, but that was probably just because his face was so scarred he couldn’t get his mouth to curl. ‘Anyone got any objections to this?’ Aside from the crackling of the fire, there wasn’t a sound. Dow stood up on his seat and shouted it. ‘Anyone want to speak up for Calder?’ None spoke.

How silly his whispers in the dark seemed now. All his seeds had fallen on stony ground all right. Dow was firmer set in Skarling’s Chair than ever and Calder hadn’t a friend to his name. His brother was dead and he’d somehow found a way to make Curnden Craw his enemy. Some spinner of webs he was.

‘No one? No?’ Slowly, Dow sat back down. ‘Anyone here not happy about this?’

‘I’m not fucking delighted,’ said Calder.

Dow burst out laughing. ‘You got bones, lad, whatever they say. Bones of a rare kind. I’ll miss you. You got a preference when it comes to method? We could hang you, or cut your head off, or your father was partial to the bloody cross though I couldn’t advise it—’

Maybe the fighting today had gone to Calder’s head, or maybe he was sick of treading softly, or maybe it was the cleverest thing to do right then. ‘Fuck yourself!’ he snarled, and spat into the fire. ‘I’d sooner die with a sword in my hand! You and me, Black Dow, in the circle. A challenge.’

Slow, scornful silence. ‘Challenge?’ sneered Dow. ‘Over what? You make a challenge to decide an issue, boy. There’s no issue here. Just you turning on your Chief and trying to talk his Second into stabbing him in the back. Would your father have taken a challenge?’

‘You’re not my father. You’re not a fucking shadow of him! He made that chain you’re wearing. Forged it link by link, like he forged the North new. You stole it from the Bloody-Nine, and you had to stab him in the back to get it.’ Calder smirked like his life depended on it. Which it did. ‘All you are is a thief, Black Dow, and a coward, and an oath-breaker, and a fucking idiot besides.’

‘That a fact?’ Dow tried to smile himself, but it looked more like a scowl. Calder might be a beaten man, but that was just the point. Having a beaten man fling shit at him was souring his day of victory.

‘Haven’t you got the bones to face me, man to man?’

‘Show me a man and we’ll see.’

‘I was man enough for Tenways’ daughter.’ Calder got a flutter of laughter of his own. ‘But what?’ And he nodded up to Shivers. ‘You get harder men to do your black work now, do you, Black Dow? Lost your taste for it? Come on! Fight me! The circle!’

Dow had no real reason to say yes. He’d nothing to win. But sometimes it’s more about how it looks than how it is. Calder was famous as the biggest coward and piss-poorest fighter in any given company. Dow’s name was all built on being the very opposite. This was a challenge to everything he was, in front of all the great men of the North. He couldn’t turn it down. Dow saw it, and he slouched back in Skarling’s Chair like a man who’d argued with his wife over whose turn it was to muck out the pigpen, and lost.

‘All right. You want it the hard way you can have it the fucking hard way. Tomorrow at dawn. And no pissing about spinning the shield and choosing weapons. Me and you. A sword each. To the death.’ He angrily waved his hand. ‘Take this bastard somewhere I don’t have to look at him smirk.’

Calder gasped as Shivers jerked him to his feet, twisted him around and marched him off. The crowd closed in behind them. Songs started up again, and laughter, and bragging, and all the business of victory and success. His imminent doom was a distraction hardly worth stopping the party for.

‘I thought I told you to run.’ Craw’s familiar voice in his ear, the old man pushing through the press beside him.

Calder snorted. ‘I thought I told you not to say anything. Seems neither of us can do as we’re told.’

‘I’m sorry it had to be this way.’

‘It didn’t have to be this way.’

He saw Craw’s grimace etched by firelight. ‘You’re right. I’m sorry this is what I chose, then.’

‘Don’t be. You’re a straight edge, everyone knows it. And let’s face the facts, I’ve been hurtling towards the grave ever since my father died. Just a surprise it’s taken me this long to hit mud. Who knows, though?’ he called as Shivers dragged him between two of the Heroes, giving Craw one last smirk over his shoulder. ‘Maybe I’ll beat Dow in the circle!’

He could tell from Craw’s sorry face he didn’t think it likely. Neither did Calder, if he was honest for once. The very reasons for the success of his little plan were also its awful shortcomings. Calder was the biggest coward and piss-poorest fighter in any given company. Black Dow was the very opposite. They hadn’t earned their reputations by accident.

He’d about as much chance in the circle as a side of ham, and everyone knew it.

Stuff Happens

‘I’ve a letter for General Mitterick,’ said Tunny, hooding his lantern as he walked up out of the dusk to the general’s tent.

Even in the limited light, it was plain the guard was a man who nature had favoured better below the neck than above it. ‘He’s with the lord marshal. You’ll have to wait.’

Tunny displayed his sleeve. ‘I’m a full corporal, you know. Don’t I get precedence?’

The guard did not take the joke. ‘Press-a-what?’

‘Never mind.’ Tunny sighed, and stood beside him, and waited. Voices burbled from the tent, gaining in volume.

‘I demand the right to attack!’ one boomed out. Mitterick. There weren’t many soldiers in the army who had the good fortune not to recognise that voice. The guard frowned across at Tunny as though to say, you shouldn’t be listening to this. Tunny held up the letter and shrugged. ‘We’ve forced them back! They’re teetering, exhausted! They’ve no stomach left for it.’ Shadows moved on the side of the tent, perhaps a shaken fist. ‘The slightest push now … I have them just where I want them!’

‘You thought you had them there yesterday and it turned out they had you.’ Marshal Kroy’s more measured tones. ‘And the Northmen aren’t the only ones who’ve run out of stomach.’

‘My men deserve the chance to finish what they’ve started! Lord Marshal, I deserve the—’

‘No!’ Harsh as a whip cracking.

‘Then, sir, I demand the right to resign—’

‘No to that too. No even more to that.’ Mitterick tried to say something but Kroy spoke over him. ‘No! Must you argue every point? You will swallow your damn pride and do your damn duty! You will stand down, you will bring your men back across the bridge and you will prepare your division for the journey south to Uffrith as soon as we have completed negotiations. Do you understand me, General?’

There was a long pause and then, very quietly, ‘We lost.’ Mitterick’s voice, but hardly recognisable. Suddenly shrunk very small, and weak, sounding almost as if there were tears in it. As if some cord held vibrating taut had suddenly snapped, and all Mitterick’s bluster had snapped with it. ‘We lost.’

‘We drew.’ Kroy’s voice was quiet now, but the night was quiet, and few men could drop eaves like Tunny when there was something worth hearing. ‘Sometimes that’s the most one can hope for. The irony of the soldier’s profession. War can only ever pave the way for peace. And it should be no other way. I used to be like you, Mitterick. I thought there was but one right thing to do. One day, probably very soon, you will replace me, and you will learn the world is otherwise.’

Another pause. ‘Replace you?’

‘I suspect the great architect has tired of this particular mason. General Jalenhorm died at the Heroes. You are the only reasonable choice. One that I support in any case.’

‘I am speechless.’

‘If I had known I could achieve that simply by resigning I would have done it years ago.’

A pause. ‘I would like Opker promoted to lead my division.’

‘I see no objection.’

‘And for General Jalenhorm’s I thought—’

‘Colonel Felnigg has been given the command,’ said Kroy. ‘General Felnigg, I should say.’

‘Felnigg?’ came Mitterick’s voice, with a tinge of horror.

‘He has the seniority, and my recommendation to the king is already sent.’

‘I simply cannot work with that man—’

‘You can and you will. Felnigg is sharp, and cautious, and he will balance you out, as you have balanced me. Though you were often, frankly, a pain in my arse, by and large it has been an honour.’ There was a sharp crack, as of polished boot heels snapping together.

Then another. ‘Lord Marshal Kroy, the honour has been entirely mine.’

Tunny and the guard both flung themselves to the most rigid attention as the two biggest hats in the army suddenly strode from the tent. Kroy made sharply off into the gathering gloom. Mitterick stayed there, looking after him, one hand opening and closing by his side.

Tunny had a pressing appointment with a bottle and a bedroll. He cleared his throat. ‘General Mitterick, sir!’

Mitterick turned, very obviously wiping away a tear while pretending to be clearing dust from his eye. ‘Yes?’

‘Corporal Tunny, sir, standard-bearer of his Majesty’s First Regiment.’

Mitterick frowned. ‘The same Tunny who was made colour sergeant after Ulrioch?’

Tunny puffed out his chest. ‘The same, sir.’

‘The same Tunny who was demoted after Dunbrec?’

Tunny’s shoulders slumped. ‘The same, sir.’

‘The same Tunny who was court-martialled after that business at Shricta?’

And further yet. The same, sir, though I hasten to point out that the tribunal found no evidence of wrongdoing, sir.’

Mitterick snorted. ‘So much for tribunals. ‘What brings you here, Tunny?’

He held out the letter. ‘I have come in my official capacity as standard-bearer, sir, with a letter from my commanding officer, Colonel Vallimir.’

Mitterick looked down at it. What does it say?’

‘I wouldn’t—’

‘I do not believe a soldier with your experience of tribunals would carry a letter without a good idea of the contents. What does it say?’

Tunny conceded the point. ‘Sir, I believe the colonel lays out at some length the reasons behind his failure to attack today.’

‘Does he.’

‘He does, sir, and he furthermore apologises most profusely to you, sir, to Marshal Kroy, to his Majesty, and in fact to the people of the Union in general, and he offers his immediate resignation, sir, but also demands the right to explain himself before a court martial – he was rather vague on that point, sir – he goes on to praise the men and to shoulder the blame entirely himself, and—’

Mitterick took the letter from Tunny’s hand, crumpled it up in his fist and tossed it into a puddle.

‘Tell Colonel Vallimir not to worry.’ He watched the letter for a moment, drifting in the broken reflection of the evening sky, then shrugged. ‘It’s a battle. We all made mistakes. Would it be pointless, Corporal Tunny, to tell you to stay out of trouble?’

‘All advice gratefully considered, sir.’

‘What if I make it an order?’

‘All orders considered too, sir.’

‘Huh. Dismissed.’

Tunny snapped out his most sycophantic salute, turned and quick-marched off into the night before anyone decided to court martial him.

The moments after a battle are a profiteer’s dream. Corpses to be picked over, or dug up and picked over, trophies to be traded, booze, and chagga, and husk to be sold to the celebrating or the commiserating at equally outrageous mark-ups. He’d seen men without a bit to their names in the year leading up to an engagement make their fortunes in the hour after. But most of Tunny’s stock was still on his horse, which was who knew where, and, besides, his heart just wasn’t in it.

So he kept his distance from the fires and the men around them, strolling along behind the lines, heading north across the trampled battlefield. He passed a pair of clerks booking the dead by lamplight, one making notes in a ledger while the other twitched up shrouds to look for corpses worth noting and shipping back to Midderland, men too noble to go in the Northern dirt. As though one dead man’s any different from another. He clambered over the wall he’d spent all day watching, become again the unremarkable farmer’s folly it had been before the battle, and picked his way through the dusk towards the far left of the line where the remains of the First were stationed.

‘I didn’t know, I just didn’t know, I just didn’t see him!’

Two men stood in barley patched with little white flowers, maybe thirty strides from the nearest fire, staring down at something. One was a nervous-looking young lad Tunny didn’t recognise, holding an empty flatbow. A new recruit, maybe. The other was Yolk, a torch in one hand, stabbing at the lad with a pointed finger.

‘What’s to do?’ growled Tunny as he walked up, already developing a bad feeling. It got worse when he saw what they were looking at. ‘Oh, no, no.’ Worth lay in a bald patch of earth, his eyes open and his tongue hanging out, a flatbow bolt right through his breastbone.

‘I thought it was Northmen!’ said the lad.

‘The Northmen are on the north side of the lines, you fucking idiot!’ snapped Yolk at him.

‘I thought he had an axe!’

‘A shovel.’ Tunny dug it out of the barley, just beyond the limp fingers of Worth’s left hand. ‘Reckon he’d been off doing what he did best.’

‘I should fucking kill you!’ snarled Yolk, reaching for his sword. The lad gave a helpless squeak, holding his flatbow up in front of him.

‘Leave it.’ Tunny stepped between them, put a restraining palm on Yolk’s chest and gave a long, painful sigh. ‘It’s a battle. We all made mistakes. I’ll go to Sergeant Forest, see what’s to be done.’ He pulled the flatbow from the lad’s limp hands and pushed the shovel into them. ‘In the meantime, you’d better get digging.’ For Worth, the Northern dirt would have to do.

‘You never have to wait long, or look far,

to be reminded of how thin the line is

between being a hero or a goat’

Mickey Mantle

End of the Road

‘He in there?’

Shivers gave one slow nod. ‘He’s there.’

‘Alone?’ asked Craw, putting his hand on the rotten handle.

‘He went in alone.’

Meaning, more’n likely, he was with the witch. Craw wasn’t keen to renew his acquaintance with her, especially after seeing her surprise yesterday, but dawn was on the way, and it was past time he was too. About ten years past time. He had to tell his Chief first. That was the right thing to do. He blew out through his puffed cheeks, grimaced at his stitched face, then turned the handle and went in.

Ishri stood in the middle of the dirt floor, hands on her hips, head hanging over on one side. Her long coat was scorched about the hem and up one sleeve, part of the collar burned away, the bandages underneath blackened. But her skin was still so perfect the torch flames were almost reflected in her cheek, like a black mirror.

‘Why fight this fool?’ she was sneering, one long finger pointing up towards the Heroes. ‘There is nothing you can win from him. If you step into the circle I cannot protect you.’

‘Protect me?’ Dow slouched by the dark window, hard face all in shadow, his axe held loose just under the blade. ‘I’ve handled men ten times harder’n Prince bloody Calder in the circle.’ And he gave it a long, screeching lick with a whetstone.

‘Calder.’ Ishri snorted. ‘There are other forces at work here. Ones beyond your understanding—’

‘Ain’t really beyond my understanding. You’re in a feud with this First of the Magi, so you’re using my feud with the Union as a way to fight each other. Am I close to it? Feuds I understand, believe me. You witches and whatever think you live in a world apart, but you’ve got both feet in this one, far as I can tell.’

She lifted her chin. ‘Where there is sharp metal there are risks.’

‘’Course. It’s the appeal o’ the stuff.’ And the whetstone ground down the blade again.

Ishri narrowed her eyes, lip curling. ‘What is it with you damn pink men, and your damn fighting, and your damn pride?’

Dow only grinned, teeth shining as his face tipped out of the darkness. ‘Oh, you’re a clever woman, no doubt, you know all kinds o’ useful things.’ One more lick of the stone, and he held the axe up to the light, edge glittering. ‘But you know less’n naught about the North. I gave my pride up years ago. Didn’t fit me. Chafed all over. This is about my name.’ He tested the edge, sliding his thumb-tip down it gently as you might down a lover’s neck, then shrugged. ‘I’m Black Dow. I can’t get out o’ this any more’n I can fly to the moon.’

Ishri shook her head in disgust. ‘After all the effort I have gone to—’

‘If I get killed your wasted effort will be my great fucking regret, how’s that?’

She scowled at Craw, and then at Dow as he set his axe down by the wall, and gave an angry hiss. ‘I will not miss your weather.’ And she took hold of her singed coat-tail and jerked it savagely in front of her face. There was a snapping of cloth and Ishri was gone, only a shred of blackened bandage fluttering down where she’d stood.

Dow caught it between finger and thumb. ‘She could just use the door, I guess, but it wouldn’t have quite the … drama.’ He blew the scrap of cloth away and watched it twist through the air. ‘Ever wish you could just disappear, Craw?’

Only every day for the last twenty years. ‘Maybe she’s got a point,’ he grunted. ‘You know. About the circle.’

‘You too?’

‘There’s naught to gain. Bethod always used to say there’s nothing shows more power than—’

‘Fuck mercy,’ growled Dow, sliding his sword from its sheath, fast enough to make it hiss. Craw swallowed, had to stop himself taking a step back. ‘I’ve given that boy all kinds o’ chances and he’s made me look a prick and a half. You know I’ve got to kill him.’ Dow started polishing the dull, grey blade with a rag, muscles working on the side of his head. ‘I got to kill him bad. I got to kill him so much no one’ll think to make me look a prick for a hundred years. Got to teach a lesson. That’s how this works.’ He looked up and Craw found he couldn’t meet his eye. Found he was looking down at the dirt floor, and saying nothing. ‘Take it you won’t be sticking about to hold a shield for me?’

‘Said I’d stick ’til the battle’s done.’

‘You did.’

‘The battle’s done.’

‘The battle ain’t ever done, Craw, you know that.’ Dow watched him, half his face in the light, the other eye just a gleam in the dark, and Craw started spilling reasons even though he hadn’t been asked.

‘There are better men for the task. Younger men. Men with better knees, and stronger arms, and harder names.’ Dow just kept watching. ‘Lost a lot o’ my friends the last few days. Too many. Whirrun’s dead. Brack’s gone.’ Desperate not to say he’d no stomach for seeing Dow butcher Calder in the circle. Desperate not to say his loyalty might not stand it. ‘Times have changed. Men the likes o’ Golden and Ironhead, they got no respect for me in particular, and I got less for them. All that, and … and …’

‘And you’ve had enough,’ said Dow.

Craw’s shoulders sagged. Hurt him to admit, but that summed it all up pretty well. ‘I’ve had enough.’ Had to clench his teeth and curl back his lips to stop the tears. As if saying it made it all catch up with him at once. Whirrun, and Drofd, and Brack, and Athroc and Agrick and all those others. An accusing queue of the dead, stretching back into the gloom of memory. A queue of battles fought, and won, and lost. Of choices made, right and wrong, each one a weight to carry.

Dow just nodded as he slid his sword carefully back into its sheath. ‘We all got a limit. Man o’ your experience needn’t ever be shamed. Not ever.’

Craw just gritted his teeth, and swallowed his tears, and managed to find some dry words to say. ‘Daresay you’ll soon find someone else to do the job—’

‘Already have.’ And Dow jerked his head towards the door. ‘Waiting outside.’

‘Good.’ Craw reckoned Shivers could handle it, probably better’n he had. He reckoned the man weren’t as far past redemption as folk made out.

‘Here.’ Dow tossed something across the room and Craw caught it, coins snapping inside. ‘A double gild and then some. Get you started, out there.’

‘Thanks, Chief,’ said Craw, and meant it. He’d expected a knife in his back before a purse in his hand.

Dow stood his sword up on its end. ‘What you going to do?’

‘I was a carpenter. A thousand bloody years ago. Thought I might go back to it. Work some wood. You might shape a coffin or two, but you don’t bury many friends in that trade.’

‘Huh.’ Dow twisted the pommel gently between finger and thumb, the end of the sheath twisting into the dirt. ‘Already buried all mine. Except the ones I made my enemies. Maybe that’s where every fighter’s road leads, eh?’

‘If you follow it far enough.’ Craw stood there a moment longer but Dow didn’t answer. So he took a breath, and he turned to go.

‘It was pots for me.’

Craw stopped, hand on the doorknob, hairs prickling all the way up his neck. But Black Dow was just stood there, looking down at his hand. His scarred, and scabbed, and calloused hand.

‘I was apprentice to a potter.’ Dow snorted. ‘A thousand bloody years ago. Then the wars came, and I took up a sword instead. Always thought I’d go back to it, but … things happen.’ He narrowed his eyes, gently rubbing the tip of his thumb against the tips of his fingers. ‘The clay … used to make my hands … so soft. Imagine that.’ And he looked up, and he smiled. ‘Good luck, Craw.’

‘Aye,’ said Craw, and went outside, and shut the door behind him, and breathed out a long breath of relief. A few words and it was done. Sometimes a thing can seem an impossible leap, then when you do it you find it’s just been a little step all along. Shivers was standing where he had been, arms folded, and Craw clapped him on the shoulder. ‘Reckon it’s up to you, now.’

‘Is it?’ Someone else came forward into the torchlight, a long scar through shaved-stubble hair.

‘Wonderful,’ muttered Craw.

‘Hey, hey,’ she said. Somewhat of a surprise to see her here, but it saved him some time. It was her he had to tell next.

‘How’s the dozen?’ he asked.

‘All four of ’em are great.’

Craw winced. ‘Aye. Well. I need to tell you something.’ She raised one brow at him. Nothing for it but just to jump. ‘I’m done. I’m quitting.’

‘I know.’

‘You do?’

‘How else would I be taking your place?’

‘My place?’

‘Dow’s Second.’

Craw’s eyes opened up wide. He looked at Wonderful, then at Shivers, then back to her. ‘You?’

‘Why not me?’

‘Well, I just thought—’

‘When you quit the sun would stop rising for the rest of us? Sorry to disappoint you.’

‘What about your husband, though? Your sons? Thought you were going to—’

‘Last time I went to the farm was four years past.’ She tipped her head back, and there was a hardness in her eye Craw wasn’t used to seeing. ‘They were gone. No sign o’ where.’

‘But you went back not a month ago.’

‘Walked a day, sat by the river and fished. Then I came back to the dozen. Couldn’t face telling you. Couldn’t face the pity. This is all there is for the likes of us. You’ll see.’ She took his hand, and squeezed it, but his stayed limp. ‘Been an honour fighting with you, Craw. Look after yourself.’ And she pushed her way through the door, and shut it with a clatter, and left him behind, blinking at the silent wood.

‘You reckon you know someone, and then …’ Shivers clicked his tongue. ‘No one knows anyone. Not really.’

Craw swallowed. ‘Life’s riddled with surprises all right.’ And he turned his back on the old shack and was off into the gloom.

He’d daydreamed often enough about the grand farewell. Walking down an aisle of well-wishing Named Men and off to his bright future, back sore from all the clapping on it. Striding through a passageway of drawn swords, twinkling in the sunlight. Riding away, fist held high in salute as Carls cheered for him and women wept over his leaving, though where the women might have sprung from was anyone’s guess.

Sneaking away in the chill gloom as dawn crept up, unremarked and unremembered, not so much. But it’s ’cause real life is what it is that a man needs daydreams.

Most anyone with a name worth knowing was up at the Heroes, waiting to see Calder get slaughtered. Only Jolly Yon, Scorry Tiptoe and Flood were left to see him off. The remains of Craw’s dozen. And Beck, dark shadows under his eyes, the Father of Swords held in one pale fist. Craw could see the hurt in their faces, however they tried to plaster smiles over it. Like he was letting ’em down. Maybe he was.

He’d always prided himself on being well liked. Straight edge and that. Even so, his dead friends long ago got his living ones outnumbered, and they’d worked the advantage a good way further the last few days. Three of those that might’ve given him the warmest send-off were back to the mud at the top of the hill, and two more in the back of his cart.

He tried to drag the old blanket straight, but no tugging at the corners was going to make this square. Whirrun’s chin, and Drofd’s, and their noses, and their feet making sorry little tents of the threadbare old cloth. Some hero’s shroud. But the living could use the good blankets. The dead there was no warming.

‘Can’t believe you’re going,’ said Scorry.

‘Been saying for years I would.’

‘Exactly. You never did.’

Craw could only shrug. ‘Now I am.’

In his head saying goodbye to his own crew had always been like pressing hands before a battle. That same fierce tide of comradeship. Only more, because they all knew it was the last time, rather than just fearing it might be. But aside from the feeling of squeezing flesh, it was nothing like that. They seemed strangers, almost. Maybe he was like the corpse of a dead comrade, now. They just wanted him buried, so they could get on. For him there wouldn’t even be the worn-down ritual of heads bowed about the fresh-turned earth. There’d just be a goodbye that felt like a betrayal on both sides.

‘Ain’t staying for the show, then?’ asked Flood.

‘The duel?’ Or the murder, as it might be better put. ‘I seen enough blood, I reckon. The dozen’s yours, Yon.’

Yon raised an eyebrow at Scorry, and at Flood, and at Beck. ‘All of ’em?’

‘You’ll find more. We always have. Few days time you won’t even notice there’s aught missing.’ Sad fact was it was more’n likely true. That’s how it had always been, when they lost one man or another. Hard to imagine it’d be the same with yourself. That you’d be forgotten the way a pond forgets a stone tossed in. A few ripples and you’re gone. It’s in the nature of men to forget.

Yon was frowning at the blanket, and what was underneath. ‘If I die,’ he muttered, ‘who’ll find my sons for me—’

‘Maybe you should find ’em yourself, you thought o’ that? Find ’em yourself, Yon, and tell ’em what you are, and make amends, while you’ve got breath still to do it.’

Yon looked down at his boots. ‘Aye. Maybe.’ A silence comfortable as a spike up the arse. ‘Well, then. We got shields to hold, I reckon, up there with Wonderful.’

‘Right y’are,’ said Craw. Yon turned and walked off up the hill, shaking his head. Scorry gave a last nod then followed him.

‘So long, Chief,’ said Flood.

‘I guess I’m no one’s Chief no more.’

‘You’ll always be mine.’ And he limped off after the other two, leaving just Craw and Beck beside the cart. A lad he hadn’t even known two days before to say the last goodbye.

Date: 2015-12-18; view: 775

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| I’m not sure how much violence and 8 page | | | I’m not sure how much violence and 10 page |