CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

The one thing the English will never forgive the Germans for is 3 page

158 16 The media

absolutely against it. So were a number of Conservative and Liberal

politicians. Over the years, however, these fears have proved to be unfounded. Commercial television in Britain has not developed the habit of showing programmes sponsored by manufacturers. There has recently been some relaxation of this policy, but advertisers have never had the influence over programming that they have had in the USA.

Most importantly for the structure of commercial television, ITV news programmes are not made by individual television companies. Independent Television News (ITN) is owned jointly by all of them. For this and other reasons, it has always been protected from com-

| Advertising Early weekday mornings Mornings and early afternoons Late afternoons Evenings |

| Weekends |

Much of weekend afternoons are devoted to sport. Saturday evenings include the most popular live variety shows.

Channel 5 Started in 1997. It is a commercial channel (it gets its money from advertising) which is received by about two-thirds of British households. Its emphasis is on entertainment (for example, it screens a film every ni^ht at peak viewing time). However, it makes all other types of programme too. Of particular note is its unconventional presentation of the news, which is designed to appeal to younger adults.

There is also a Welsh language channel for viewers in Wales.

| mercial influence. There is no significant difference between the style and content of the news on ITV and that on the BBC. The same fears about the quality of television programmes that were expressed when ITV started are now heard with regard to satellite and cable television. This time the fears may be more justified, as the companies that run satellite and cable television channels are in a similar commercial and legal position to those which own the big newspapers (and in some cases are actually the same companies). However, only about a third of households receive satellite and/or cable, and so far these channels have not significantly reduced the viewing figures for the main national channels. Television: style Although the advent of ITV did not affect television coverage of news and current affairs, it did cause a change in the style and content of other programmes shown on television. The amount of money that a television company can charge an advertiser depends on the expected number of viewers at the time when the advertisement is to be shown. Therefore, there was pressure on ITV from the start to make its output popular. In its early years ITV captured nearly three-quarters of the BBC's audience. The BBC then responded by making its own programmes equally accessible to a mass audience. Ever since then, there has been little significant difference in what is shown on the BBC and commercial television. Both BBC1 and ITV (and also the more recent Channel 5) show a wide variety of programmes. They are in constant competition with each other to attract the largest audience (this is known as the ratings war). But they do not each try to show a more popular type of programme than the other. They try instead to do the same type of programme 'better'. Of particular importance in the ratings war is the performance of the channels' various soap operas. The two most popular and long-running of these, which are shown at least twice a week, are not glamorous American productions showing rich and powerful people (although series such as Dallas and Dynasty are sometimes shown). They are ITV's Coronation Street, which is set in a working-class area near Manchester, and BBC 1 's EastEnders, which is set in a working-class area of London. They, and other British-made soaps and popular comedies, certainly do not paint an idealized picture of life. Nor are they very sensational or dramatic. They depict (relatively) ordinary lives in relatively ordinary circumstances. So why are they popular? The answer seems to be that their viewers can see themselves and other people they know in the characters and, even more so, in the things that happen to these characters. The British prefer this kind of pseudo-realism in their soaps. In the early 1990s, the BBC spent a lot of money filming a new soap called Eldorado, set in a small Spanish village which was home to a large number of expatriate British people. Although the BBC used its most |

| > Glued to the goggle box As long ago as 1953, it was estimated that twenty million viewers watched the BBC's coverage of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. By1970, 94% of British households had a television set (known colloquially as a 'goggle box'), mostly rented rather than bought. Now, 99% of households own or rent a television and the most popular programmes are watched by as many people as claim to read the Sun and the Daily Mirror combined. Television broadcasting in Britain has expanded to fill every part of every day of the week. One of the four channels (ITV) never takes a break (it broadcasts for twenty-four hours) and the others broadcast from around six in the morning until after midnight. A survey reported in early 1994 that 40% of British people watched more than three hours of television every day; and 16% watched seven hours or more! Television news is watched every day by more than half of the population. As a result, its presenters are among the best-known names and faces in the whole country — one of them once boasted that he was more famous than royalty! |

160 16 The media

| > The ratings: a typical week The ratings are dominated by the soaps (Coronation Street, EastEnders, Neighbours and Emmerdale) and soap-style dramas (Casualty, which is set in a hospital, and The Bill, which is about the police). Light-entertainment talk shows also feature prominently (e.g. This Is Your Life, Barrymore and Noel's House Party) and quiz shows are sometimes very popular (e.g. Countdown). It is unusual that only one comedy programme appears below (Red Dwarf). Certain cinema films can also get high ratings (marked ** below). Science fiction remains a popular genre; Quantum Leap and Red Dwarf are both long-running series. Sports programmes appear in the top ten when they feature a particular sporting |

| occasion. This happens frequently. There is one example in the list below (The Big Fight Live). The list includes just one representative of 'high culture': the dramatization of the novel Middlemarch, by the nineteenth century author George Eliot. There are two documentaries, a travel series (Great Railway Journeys) and a science series (Horizon). The Antiques Roadshow comes from a different location in the country every week. In it, local people bring along objects from their houses and ask experts how much they are worth. Apart from the films, there is only one American programme in the list below (Quantum Leap). |

|

* Average for the week (programmes shown more than once a week) ** Film

Source: BARB (Broadcasters'Audience Research Board Ltd)

Question and suggestion 161

successful soap producers and directors, it was a complete failure. Viewers found the complicated storylines and the Spanish accents too difficult to follow, and could not identify with the situations in which the characters found themselves. It was all just too glamorous for them. It was abandoned after only a year.

It became obvious in the early i 96os that the popularity of soap operas and light entertainment shows meant that there was less room for programmes which lived up to the original educational aims of television. Since 1982 Britain has had two channels (BBC2 and Channel 4) which act as the main promoters of learning and 'culture'. Both have been successful in presenting programmes on serious and weighty topics which are nevertheless attractive to quite large audiences. BBC2 is famous for its highly acclaimed dramatizations of great works of literature and for certain documentary series that have become world-famous 'classics' (the art history series Civilisation and the natural history series Life On Earth are examples). Another thing that these channels do well, particularly Channel 4, is to show a wide variety of programmes catering to minority intersts - including, even, subtitled foreign soap operas!

QUESTIONS

1 It is easy to tell by the size and shape of British newspapers what kinds.of readers they are aimed at. What are the two main types called, and who reads them? What other differences are there between newspapers? Are there similarly clear distinctions between types of newspaper in your country?

2 The dominant force in British Broadcasting is the BBC. What enabled it to achieve its position, and how does it maintain this? Can you describe some of the characteristics which give the BBC its special position in Britain and in the rest of the world?

3 There is one aspect of newspaper publishing which, in the 1980s and 1990s, received a lot of public and parliamentary criticism. People

felt that the invasion of privacy of private individuals and public figures (such as members of the royal family) had reached unacceptable levels. Legislation was drafted, but there was no new law passed to control the press's activities. What problems are there in Britain with getting legislation like this approved? What arguments can be put forward in favour of keeping the status quo? How is the press controlled in your country?

4 What does the television ratings chart tell you about British viewing habits? Does this tell you anything about the British? What are the most popular television programmes in your country? What does this reveal, if anything, about your nation?

SUGGESTIONS

* Have a look at a couple of examples of each type of national newspaper. Try to get hold of examples from the same day. * If you don't already do so, listen to the BBC World Service if you can.

| >. The romance of travel: the steam engine Perhaps because they were the first means of mass transportation, perhaps because they go through the heart of the countryside, there is an aura of romance attached to trains in Britain. Many thousands of people are enthusiastic 'train spotters' who spend an astonishing amount of time at stations and along the sides of railway lines trying to 'spot' as many different engines as possible. Steam trains, symbolizing the country's lost industrial power, have the greatest romance of all. Many enthusiasts spend their free time keeping them in operation and finance this by offering rides to tourists. In 1993 more than 10 million journeys were taken on steam trains in Europe. More than 80% of those journeys were taken in Britain. > The AA and the RAC These are the initials of the Automobile Association and the Royal Automobile Club. A driver who joins either of them (by paying a subscription) can get emergency help when his or her car breaks down. The fact that both organizations are very well-known is an - indication of the importance of the car in modern British life. |

|

| The British are enthusiastic about mobility. They regard the opportunity to travel far and frequently as a right. Some commuters spend up to two or three hours each day getting to work in London or some other big city and back home to their suburban or country homes in the evening. Most people do not spend quite so long each day travelling, but it is taken for granted that few people live near enough to their work or secondary school to get there on foot. As elsewhere in Europe, transport in modern Britain is dominated by the motor car and there are the attendant problems of traffic congestion and pollution. These problems are, in fact, more acute than they are in many other countries both because Britain is densely populated and also because a very high proportion of goods are transported by road. There is an additional reason for congestion in Britain. While the British want the freedom to move around easily, they do not like living near big roads or railways. Any proposed new road or rail project leads to 'housing blight'. The value of houses along or near the proposed route goes down. Every such project is attended by an energetic campaign to stop construction. Partly for this reason, Britain has, in proportion to its population, fewer kilometres of main road and railway than any other country in northern Europe. Transport policy is a matter of continual debate. During the 1980s the government's attitude was that public transport should pay for itself (and should not be given subsidies) and road building was given priority. However, the opposite point of view, which argues in favour of public transport, has become stronger during the 1990s, partly as a result of pressure from environmental groups. It is now generally accepted that transport policy should attempt to more than merely accommodate the predicted doubling in the number of cars in the next thirty years, but should consider wider issues. On the road Nearly three-quarters of households in Britain have regular use of a car and about a quarter have more than one car. The widespread enthusiasm for cars is, as elsewhere, partly a result of people using them to project an image of themselves. Apart from the obvious status indicators such as size and speed, the British system of vehicle regis- |

| (ration introduces another. Registration plates, known as 'number plates', give a clear indication of the age of cars. Up to 1999 there was a different letter of the alphabet for each year and in summer there were a lot of advertisements for cars on television and in the newspapers because the new registration 'year' began in August. Another possible reason for the British being so attached to their cars is the opportunity which they provide to indulge the national passion for privacy. Being in a car is like taking your 'castle' with you wherever you go (see chapter 19). Perhaps this is why the occasional attempts to persuade people to 'car pool' (to share the use of a car to and from work) have met with little success. The privacy factor may also be the reason why British drivers are less 'communicative' than the drivers of many other countries. They use their horns very little, are not in the habit of signalling their displeasure at the behaviour of other road users with their hands and are a little more tolerant of both other drivers and pedestrians. They are also a little more safety conscious. Britain has the best road safety record in Europe. The speed limit on motorways is a little lower than in most other countries (70 mph =112 kph) and people go over this limit to a somewhat lesser extent. In addition, there are frequent and costly government campaigns to encourage road safety. Before Christmas 1992, for instance, £ 2.3 million was spent on such a campaign. Another indication that the car is perceived as a private space is that Britain was one of the last countries in western Europe to introduce the compulsory wearing of seat belts (in spite of British concern for safety). This measure was, and still is, considered by many to be a bit of an infringement of personal liberty. The British are not very keen on mopeds or motorcycles. They exist, of course, but they are not private enough for British tastes. Every year twenty times as many new cars as two-wheeled motor vehicles are registered. Millions of bicycles are used, especially by younger people, but except in certain university towns such as Oxford and Cambridge, they are not as common as they are in other parts of north-western Europe. Britain has been rather slow to organize special cycle lanes. The comparative safety of the roads means that parents are not too worried about their children cycling on the road along with cars and lorries. Public transport in towns and cities Public transport services in urban areas, as elsewhere in Europe, suffer from the fact that there is so much private traffic on the roads that they are not as cheap, as frequent or as fast as they otherwise could be. They also stop running inconveniently early at night. Efforts have been made to speed up journey times by reserving certain lanes for buses, but so far there has been no widespread attempt to give priority to public transport vehicles at traffic lights. |

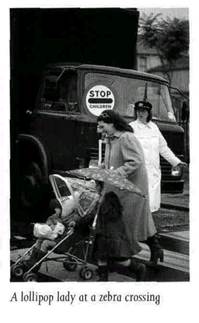

| > The decline of the lollipop lady In 19^3 most schoolchildren walked to school. For this reason, school crossing patrols were introduced. A 'patrol' consists of an adult wearing a bright waterproof coat and carrying a red-and-white stick with a circular sign at the top which reads STOP, CHILDREN. Armed with this 'lollipop', the adult walks out into the middle of the road, stops the traffic and allows children to cross. 'Lollipop ladies ' (80% of them are women) are a familiar part of the British landscape. But since the 1980s, they have become a species in decline. So many children are now driven to school by car that local authorities are less willing to spend money on them. However, because there are more cars than there used to be, those children who are not driven to school need them more than ever. The modern lollipop lady has survived by going commercial! In 1993 Volkswagen signed a deal to dress London's 1 ,000 lollipop ladies in coats which bear the company's logo. Many other local authorities in the country arranged similar deals. |

|

Public transport in towns and cities 163

| 164 17 Transport > The road to hell The M25; is the motorway which circles London. Its history exemplifies the transport crisis in Britain. When the first section was opened in 1963 it was seen as the answer to the area's traffic problems. But by the early 1990s the congestion on it was so bad that traffic jams had become an everyday occurrence. A rock song of the time called it 'the road to hell'. In an effort to relieve the congestion, the government announced plans to widen some parts of it to fourteen lanes - and thus to import from America what would have been Europe's first 'super highways'. This plan provoked widespread opposition. > What the British motorist hates most Traffic wardens are not police officers, but they have the force of law behind them as they walk around leaving parking tickets on the windscreens of cars that are illegally parked. By convention, they are widely feared and disliked by British motorists. Every year there are nearly a hundred serious attacks on them. In 1993 government advisers decided that their image should change. They were officially renamed 'parking attendants' (although everyone still calls them traffic wardens). Traffic cones are orange and white, about a metre tall and made of plastic. Their appearance signals that some part of the road ahead (the part marked out by the cones) is being repaired and therefore out of use, and that therefore there is probably going to be a long delay. Workers placing them in position have had eggs thrown at them and lorry drivers have been accused by police of holding competitions to run them down. On any one day at least 100,000 of them are in use on the country's roads. |

| An interesting modern development is that trams, which disappeared from the country's towns during the i 9^os and i 96os, are now making a comeback. Research has shown that people seem to have more confidence in the reliability of a service which runs on tracks, and are therefore readier to use a tram than they would be to use an ordinary bus. Britain is one of the few countries in Europe where double-decker buses (i.e. with two floors) are a common sight. Although single-deckers have also been in use since the i 96os, London still has more than 3,000 double-deckers in operation. In their original form they were 'hop-on, hop-off' buses. That is, there were no doors, just an opening at the back to the outside. There was a conductor who walked around collecting fares while the bus was moving. However, most buses these days, including double-deckers, have separate doors for getting on and off and no conductor (fares are paid to the driver). The famous London Underground, known as 'the tube', is feeling the effects of its age (it was first opened in 1863). It is now one of the dirtiest and least efficient of all such systems in European cities. However, it is still heavily used because it provides excellent connections with the main line train stations and with the suburbs surrounding the city. Another symbol of London is the distinctive black taxi (in fact, they are not all black these days, nor are they confined to London). |

|

| According to the traditional stereotype, the owner-drivers of London taxis, known as cabbies, are friendly Cockneys (see chapter 4) who never stop talking. While it may not be true that they are all like this, they all have to demonstrate, in a difficult examination, detailed familiarity with London's streets and buildings before they are given their licence. (This familiarity is known simply as 'the knowledge'.) Normally, these traditional taxis cannot be hired by phone. You simply have to find one on the street. But there are also many taxi companies who get most of their business over the phone. Their taxis are known as 'minicabs'. They tend to have a reputation, not always justified, for unreliability as well as for charging unsuspecting tourists outrageous prices (in common with taxis all over the world). However, taxis and minicabs are expensive and most British people rarely use them, except, perhaps, when going home late at night after public transport has stopped running, especially if they have been drinking alcohol. Public transport between towns and cities It is possible to travel on public transport between large towns or cities by road or rail. Coach services are generally slower than trains but are also much cheaper. In some parts of the country, particularly the south-east of England, there is a dense suburban rail network, but the most commercially successful trains are the Inter-City services that run between London and the thirty or so largest cities in the country. The difference between certain trains is a fascinating reflection of British insularity. Elsewhere in Europe, the fastest and smartest trains are the international ones. But in Britain, they are the Inter-City trains. The international trains from London to the Channel ports of Newhaven, Dover and Ramsgate are often uncomfortable commuter trains stopping at several different stations. The numbers of trains and train routes were slowly but continuously reduced over the last forty years of the twentieth century. In October 1993 the national train timetable scheduled 10,000 fewer trains than in the previous October. The changes led to many complaints. The people of Lincoln in eastern England, for example, were worried about their tourist trade. This town, which previously had fifteen trains arriving on a Sunday from four different directions, found that it had only four, all arriving from the same direction. The Ramblers' Association (for people who like to go walking in the countryside) were also furious because the ten trains on a Sunday from Derby to Matlock, near the highest mountains in England, had all been cancelled. At the time, however, the government wanted very much to privatize the railways. Therefore, it had to make them look financially attractive to investors, and the way to do this was to cancel as many unprofitable services as possible. |

| Pablic transport 165 >Queueing An Englishman, even if he is alone,forms an orderly queue of one. GEORGE MIKES Waiting for buses allows the British to indulge their supposed passion for queueing. Whether this really signifies civilized patience is debatable (see chapter 5). But queueing is certainly taken seriously. When buses serving several different numbered routes stop at the same bus stop, instructions on it sometimes tell people to queue on one side for some of the buses and on the other side for others. And yes, people do get offended if anybody tries to 'jump the queue'. |

| > The dominance of London The arrangement of the country's transport network illustrates the dominance of London. London is at the centre of the network, with a 'web' of roads and railways coming from it. Britain's road-numbering system, (M for motorways, then A, B and C class roads) is based on the direction out of London that roads take. It is notable that the names of the main London railway stations are known to almost everybody in the country, whereas the names of stations in other cities are only known to those who use them regularly or live nearby. The names of the London stations are: Charing Cross, Euston, King's Cross, Liverpool Street, Paddington, St Pancras, Victoria, Waterloo. Each runs trains only in a certain direction out of London. If your journey takes you through London, you have to use the Underground to get from one of these stations to another. |

16617 Transport

| >Le compromise One small but remarkable success of the chunnel (the Channel tunnel) enterprise seems to be linguistic. You might think that there would have been some argument. Which language would be used to talk about the chunnel and things connected with it? English or French? No problem! A working compromise was soon established, in which English nouns are combined with French words of other grammatical classes. For example, the company that built the chunnel is called Trans-monche Link (la Manche is the French name for the Channel), and the train which carries vehicles through the tunnel is officially called Le Shuttle. This linguistic mixing quickly became popular in Britain. On i12 February 1994, hundred of volunteers walked the 50 kilometres through the chunnel to raise money for charity. The Daily Mail, the British newspaper that organized the event, publicized it as 'Le walk', and the British media reported on the progress of 'Les walkers'. |

| The story of the chunnel On Friday 6 May 1994, Queen Elizabeth II of Britain and President Mitterand of France travelled ceremonially under the sea that separates their two countries and opened the Channel tunnel (often known as 'the chunnel') between Calais and Folkestone. For the first time ever, people were able to travel between Britain and the continent without taking their feet off solid ground. The chunnel was by far the biggest building project in which Britain was involved in the twentieth century. The history of this project, however, was not a happy one. Several workers were killed during construction, the price of construction turned out to be more than double the £4.5 billion first estimated and the start of regular services was repeatedly postponed, the last time even after tickets had gone on sale. On top of all that, the public showed little enthusiasm. On the day that tickets went on sale, only 138 were sold in Britain (and in France, only 12!). On the next day, an informal telephone poll found that only 5% of those calling said that they would use the chunnel. There were several reasons for this lack of enthusiasm. At first the chunnel was open only to those with private transport. For them, the small saving in travel time did not compensate for the comparative discomfort of travelling on a train with no windows and no facilities other than toilets on board, especially as the competing ferry companies had made their ships cleaner and more luxurious. In addition, some people felt it was unnatural and frightening to travel under all that water. There were also fears about terrorist attacks. However unrealistic such fears were, they certainly interested Hollywood. Every major studio was soon planning a chunnel disaster movie! The public attitude is becoming more positive, although very slowly. The direct train services between Paris and London and Brussels and London seem to offer a significant reduction of travel time when compared to travel over the sea, and this enterprise has been more of a success. At the time of writing, however, the highspeed rail link to take passengers between the British end of the chunnel and London has not been completed. Air and water A very small minority, of mostly business people, travel within Britain by air. International air travel, however, is very important economically to Britain. Heathrow, on the western edge of London, is the world's busiest airport. Every year, its four separate terminals are used by more than 30 million passengers. In addition, Gatwick Airport, to the south of London, is the fourth busiest passenger airport in Europe. There are two other fairly large airports close to London (Stansted and Luton) which deal mainly with charter flights, |

Date: 2015-12-18; view: 2718

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| The one thing the English will never forgive the Germans for is 2 page | | | The one thing the English will never forgive the Germans for is 4 page |