CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Part V: Word-Formation 3 page

Morphological motivation is the relationship between morphemes. All one-morpheme words (e.g., bring, cut, reach, room, and build) are unmotivated. In words composed of more than one morpheme, “the carrier of the word-meaning is the combined meaning of the component morphemes and the meaning of the structural pattern of the word” (Ginzburg at al., p.25). The derived word re-submit is motivated because its morphological structure suggests the idea of submitting again. In this example, we can observe a direct connection between the structural pattern of the word and its meaning. Morphological motivation is relative, and the degree of motivation varies: there exist various grades of motivation, ranging from the extremes of complete motivation (e.g., endless) to lack of motivation (e.g., matter, number, and repeat). An example of partial motivation is cranberry. There is no lexical meaning in the morpheme cran-, but the lexemes blackberry and blueberry are examples of complete morphological motivation (blue + berry and black + berry); they are named for the color of their berries. The lexeme raspberry is also motivated because it takes its name from English rasp (to scrape roughly), in reference to the thorny canes bearing the berries. Morphological motivation is understood as a direct connection between the lexical meaning of the component morphemes, the pattern of their arrangement, and the meaning of the word. The degree of morphological motivation may be partial and complete. There are cases where unmotivated words are observed.

Semantic motivation is the “co-existence of direct and figurative meanings of the same word within the same synchronous system” (Arnold, p.34). It functions as an association between the primary and secondary (derived) meanings of a word based on a metaphorical extension of the primary meaning. Metaphorical extension may be viewed as “generalisation of the denotative meaning of a word permitting it to include new referents which are in some way like the original class of referents” (Ginzburg at al., 1979, p. 27), e.g., foot and the foot of the mountain. Metaphor is a word or a phrase that does not carry the literal meaning of a lexeme or a phrase but is a figurative meaning. Similarity of various aspects and/or functions of different classes of referents may account for the semantic motivation of a number of minor meanings (Ginzburg et al., 1979, p. 27); for example, any extension associated with foot is semantically motivated (foot locker, football, footnote, flatfoot, footage, and the foot of the mountain. Metaphoric extension may be observed in the so-called trite metaphors, such as foot the bill, footloose and fancy-tree, get off on the wrong foot, have a foot in the door, not to put a foot wrong, put one’s best foot forward, put one’s foot down, and put one’s foot in it). Semantic motivation suggests a direct connection between the primary and figurative meanings of the word. This connection may be understood as a metaphoric extension of the primary meaning based on the similarity of different classes of referents denoted by the word.

6.5 Semantics and Change of Meaning

The meaning of a lexeme is what we understand and intend when we use it. The way our language formulates the meaning influences the manner we respond to the world and perceive it. Language clearly affects our daily activities and habits of thought. The meanings of lexemes vary with place, time, and situation or circumstance. Moreover, in the course of language development, the meanings of the lexemes can change. With the expansion and development of computer technology, lexemes may acquire new meanings, e.g., bookmark, boot, floppy, mail, mouse, notebook, save, server, spam, surf, virtual, virus, wall-paper, web, window, zip, and others. Sometimes it is difficult to predict how lexemes will change, but it is not a chaotic process—it follows certain paths. If we utter the word winter, connotation creates a set of associations such as snow, white, bitter cold, and frozen cheeks. These associations create the connotation of the word, but they cannot be its meaning. Words change in both their senses and their associations. John Algeo claims that the following changes are possible within denotation:

A sense may expand to include more referents than it formerly had (generalization), contract to include fewer referents (specialization), or shift to include a quite different set of referents (transfer of meaning). The associations of a word may become worse (pejoration) or better (amelioration) and stronger or weaker than they formerly were. (p.210)

Under generalization he understands that the meaning can be generalized (broadened, widened, and extended). When the scope of a lexeme is increased, the number of features in its definition is reduced. For example, the lexeme barn is a compound of Old English bere (barley) and ern (storage), which originally was a place to store barley. Eventually, the lexeme barn broadened its meaning, thus becoming more generalized, and now we have car barns, furniture barns, and antique barns. A very interesting explanation of the lexeme corn is given in the Encyclopedia. The Old Teutonic kurnom eventually became Old Saxon korn and then corn in Old English, which is maize for the British and any grain for the Americans. When in Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale,” a homesick Ruth stands “in tears amid the alien corn,” she is standing in a field of wheat or rye, any grain but New World corn (Hendrickson, 1997, p.170).

The opposite of generalization is specialization, “a process in which, by adding to the features of meaning, the referential scope of a word is reduced” (Algeo, 2011, p. 210). This process indicates that a word’s meaning becomes less general and more specialized. The lexeme deer originated from Old English deór which meant ‘any wild animal.’ In King Lear Shakespeare writes, “But mice and rats and such small deer have been in Tom's food for seven long year” (3.4.151). Only in relatively modern times has the word deer come to mean only the species we identify with the term today. The lexeme girl came to English from German gore (a young person). In some Scottish dialects, girl still means either a young male or female. Meat in Middle English meant food in general. The word became confined to the flesh of animals when there was a large increase in flesh eating, and meat lost its generalized meaning for any kind of food by the 17th century (Hendrickson, 1997, p. 446).

There are many ways to transfer a lexeme’s or a phrase’s meaning. Transfers of meaning are linguistic mechanisms when we use the same lexeme or same expression to refer to disjointed sorts of things.

Metaphor

Metaphor has traditionally been observed in literary or poetic language, and it is viewed as the most important form of figurative language. Metaphor causes transference, where properties are transferred from one concept to another. Metaphor originates from Greek, which stands for "transfer" (meta and trans meaning "across"; phor and fer meaning "carry"): to carry something across. Hence, a metaphor treats something as if it were something else. To grasp an idea is radically different from grasping an object. Money becomes a nest egg; a sandwich, a submarine. A metaphor is a transfer of name based on the association of similarity, suggesting a likeness or analogy between them. It is an implicit comparison or identification of one thing with another unlike itself without the use of a verbal signal. A cunning person, for instance, is referred to as a fox. Thus, one of the connotations of fox is cleverness. “Metaphors allow us to understand one domain of experience in terms of another. To serve this function, there must be some grounding, some concepts that are not completely understood via metaphor to serve as source domains” (Lakoff & Turner, 1989, p. 135).

Some metaphors involve the use of words which are primarily associated with spatial orientation when we talk about physical and psychological states. These metaphors are called spatial, or orientational, metaphors. Being on one’s back (physically down) indicates that a person is either unhappy or sick; however, if someone is happy and in good health, then this involves being on one’s feet (physically up). These metaphors give the notion of special orientation and are bases on physical and cultural experience (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980, p. 14).

Another group of metaphors is identified, which Lakoff and Johnson (1980) name ontological metaphors, where an individual’s experience of non- physical phenomena is described in terms of simple physical objects like substances and containers (pp. 29-30).

Kristin Denham and Anne Lobeck classify metaphors variously as dead metaphors, mixed metaphors, personification, and synesthesia. Dead metaphors are those that are so “conventionalized in everyday speech that we do not even realize they are metaphors” (p. 306), e.g. He is blind to new ideas. I see your point. Blind and see have nothing to do with visual perception. They are so common in the language that individuals do not even think that they are metaphors. Mixed metaphors consist of “parts of different metaphors [that] are telescoped into one utterance” (p. 306). The examples of mixed metaphors are the following: to get into hot water skating on thin ice; to zip one's lips and throw away the key, and others. In personification, human attributes are given to inanimate objects. William Blake’s poem “Ah! Sunflower” is based on personification:

"Ah, William, we're weary of weather,"

said the sunflowers, shining with dew.

"Our traveling habits have tired us.

Can you give us a room with a view?"

They arranged themselves at the window

and counted the steps of the sun,

and they both took root in the carpet

where the topaz tortoises run.

One of the roles of metaphor is the creation of new words or phrases. The coining of the phrase “computer virus, a specific type of harmful program, is based on a conceptual model of biological viruses which is generalized or schematized away from the biological details” (Saeed, 2009, p. 362).

Synesthesia is “a type of metaphorical language in which one kind of sensation is described in terms of another” (p.307). Color may be attributed to sounds, odor to color, sound to odor, etc.). The meaning may be transferred from one sensory faculty to another, as when we use clear for what we can hear rather than see, as in clear sound. Loud may be transferred from hearing to sight, when we speak of loud colors. Sweet primarily refers to taste, and it may be extended to hearing, as in sweet music, and others.

Change of meaning is often due to association of ideas, whether by metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, or others. In metonymy, an associated idea stands in for the actual item. For example, The pen is mightier than the sword is an elegant way of saying that literature and propaganda accomplish more and survive longer than warfare. Another example is The White House announced, which means is ‘the President announced.’ In the sentence The pizza is waiting for his check, the pizza stands for a person who has ordered pizza.

The understanding of one thing by another, in which a part stands for the whole or the whole for a part, is called synecdoche: a hired hand means ‘a laborer’; strong bodies mean ‘strong people.’ Silver has come to be used for eating utensils made of silver— an instance of synecdoche— and sometimes, by association, for flatware made of other substances, so that we may speak of stainless steel or even plastic silverware.

In addition to a change in its sense or literal meaning, a word may also undergo change in its associations, especially of value. A word may go downhill, or it may rise in the world-- there is no way of predicting what will happen to a lexeme. Politician has had a downhill development, or pejoration(from Latin pejor ‘ worse’): Politicians, whores, and buildings all get respectable after they get old (from the movie Chinatown, 1974). Lewd, beginning with its original meaning ‘lay, as in layman, has had seven different meanings through the years: unlettered, low, bungling, vile, lawless, licentious, and finally ‘obscene,’ which is the only meaning that survives.

The opposite of pejoration is amelioration, the improvement in value of a word. The lexeme “praise started out indifferently— it is simply appraise, ‘put a value on,’ with loss of its initial unstressed syllable (aphesis)” (Angeo, p.214), and later praise acquired a new meaning: ‘to express a favorable judgment’ or ‘to glorify, especially by the attribution of perfections.’ Nice has undergone a complete change in meaning since it came into English in the 13th century. Deriving from Latin nescius (ignorant), nice originally meant ‘foolish’ or ‘simple-minded’ and later came to mean ‘wanton’ or ‘ill-mannered’ before another century passed. By the early 1400s, nice was used for ‘extravagant dress’ which later changed its meaning to ‘fashionable dress,’ and during Shakespeare’s time, nice was used for ‘fastidious’ or ‘refined.’

As we have seen in this chapter, the meaning of every lexeme is susceptible to change, and some lexemes have changed their meanings radically in the course of the history.

Part VII: Sense Relations

“The sense of an expression is a function of the senses of its component lexemes and of their occurrence in a particular grammatical construction (Lyons, 1977, p.206). Lyons further explains that sense is here defined “to hold between the words or expressions of a single language independently of the relationship, if any, which holds between those words or expressions and their referents or denotata” (p.206). He also draws a line between a sense and a meaning. Regarding the sense, we ask the question, “What is the sense of such a word or expression?--instead of “What is the meaning of such a word or an expression?” Sense is an internal relation. Lyons further analyzes that the relationship of denotation is logically basic: we know that cow and animal are related in a certain way because denotatum of cow is included into the denotatum of animal. However, the problem occurs with such a word as a unicorn, which does not have denotation. The sentence There is no such animal as a unicorn is understandable; however, There is no such book as a unicorn is odd because animal and unicorn are related in sense, but a unicorn and a book are not related; therefore, it is a nonsensical sentence. Even if the words and expressions do not have denotation, they still may have sense.

We should also draw the distinction between reference and sense. Reference deals with “the relationship between linguistic elements, words, sentences, etc., and the non-linguistic world of experience” (Palmer, 1981, p. 29), while sense deals with “the complex system of relationships that hold between the linguistic elements themselves and is concerned with extralinguistic relations” (p. 29).

Words and phrases can enter into a variety of sense relations with other words and phrases in the language. “The sense of an expression is its place in a system of semantic relationships with other expressions in the language” (Hurford, Heasley, & Smith, 2010, p. 29). These sense relations are synonymy, antonymy, polysemy, and hyponymy.

7.1 Similarity of Sense

The first sense relation is synonymy. This term comes from the Greek, indicating ‘likeness of meaning.’ Synonyms are lexemes which have the same sense; however, there may not be perfect synonyms, which could substitute each other in all contexts. There may be slight differences between a pair of synonyms. There are dialect differences as well; for example, autumn and fall are synonymous, but the former is used more in British English, while the latter belongs to American English. Other examples are billfold (Am.)--wallet (Br.), drapes (Am.)--curtains (Br.), sidewalk (Am.)--pavement (Br.), and others. Synonyms can be differentiated stylistically; for instance, the following lexemes are synonymous: psychotic, psychopathic, demented, insane, deranged, lunatic, crazy, and mad—they all refer to serious disturbances in mind. Psychotic, psychopathic, demented, deranged, and insane can be used in a formal setting; however, mad, crazy, and lunatic may be used informally. Other examples of stylistically different synonyms are astonished—gobsmacked , crash—prang, drunk—sloshed, heart—ticker, insane—barmy, and others. There may also be collocational differences, too. The following adjectives-- strong, hardy, muscular, powerful, sturdy, and tough-- are synonymous, but they can collocate with only certain words; for example, strong pertains to what has force or to what is rugged in construction or build: a strong headwind, a strong body, and a strong workbench. It can also apply to what is vigorous, intense, vivid, or persuasive: a strong government, a strong argument, strong tea, strong colors, and a strong suspicion. The adjective powerful may appear in combination: a powerful nuclear bomb and a powerful turbine. Muscular is limited in combination; it can occur in the phrase a muscular athlete and others, suggesting ‘a well-built body.’ Sturdy and hardy are restricted to something which is durable and resistant: a sturdy footbridge, a hardy species of corn, and a hardy life. The adjective tough appears in combinations with recruits and problem: a tough problem and tough recruits. Differences exist in connotation. A pair of words may share a denotative meaning, but their connotative meanings are different; for example, persuade is a more general term, but coax, cajole, and wheedle add the connotation of gentleness, tact, even artfulness.

Howard Jackson and Etienne Zé Amvela differentiate between strict, or absolute, and loose synonyms. They state that some synonyms are “interchangeable in all their possible contexts” (p.108). Speakers may have a free choice in their use, with no effect on the meaning, e.g., homeland—motherland. All the linguists agree that strict synonyms create unnecessary redundancy in the language; therefore, one of the strict synonyms may undergo some semantic changes. When a Scandinavian lexeme sky was borrowed, it came into competition with the existing native lexeme heaven. In the course of language development, heaven narrowed its meaning to denote a spiritual concept, while sky denotes the physical notion.

When we speak of synonymy, we mean various degrees of loose synonyms. As we mentioned earlier, almost all the synonyms differ from each other in their shades of meaning, whether it is dialectal or stylistic. Loose synonyms cannot replace each other because they share different contexts, and their meanings diverge, at least slightly. Many linguists argue that it would be inefficient for a language to have strict synonyms where meanings are absolutely identical in all contexts. Accuracy of meaning would be improved, but nuance and subtlety would be sacrificed.

7.2 Oppositeness of Sense

The second semantic relation is antonymy, which is the sense relation that exists between lexemes fundamentally opposite in meaning. Brown defines antonymy as “a relation in which two lexemes share all relevant properties except for one that causes them to be incompatible” (p.26), which is polarity of meanings. The lexemes freedom and book cannot be compared because they do not share a common semantic ground on which they are contrasted. However, antonyms may realize their relation in the context where items share a common ground or if they hold the same sense. This feature depends on the context and situation; for example, in discussing colors, dull and bright are antonymous, but if dull characterizes a person, then the antonym of dull is sharp or bright. If dull is used in reference to blades or knives, then the antonym of dull is sharp.

There are several ways where lexemes can be opposites. One of them is complementary, or contradictory, pairs. Complementary antonyms are the ones, whose “senses completely bisect some domain” (Brown, p.26). Complementary antonyms do not have a middle ground; they are absolute opposites. There may exist only two possibilities—either one or the other. “The items complement each other in their meaning, and thus are known as complementary antonyms” (Crystal, p. 165). The examples of complementary antonyms are man—woman, girl—boy, married—single, dead—alive, win—lose, exit -- entrance, sink -- float, true -- false, pass -- fail, legal—illegal, and others.

The second group of antonyms is called gradable,orpolar,antonyms, which include “the concept of scale between two endpoints” (Tserdanelis & Wong, p. 225). If two antonyms are opposite in meaning, and at the same time there can be seen endpoints of some scale (temperature, height, size, age, and others), then they are gradable antonyms. Gradable antonyms have a middle ground. The examples of gradable antonyms include toward – away, hot—cold, good—bad, slow—fast, rapid—slow, and others. One solution to gradable antonyms is to treat the items as polysemous, “having relative and absolute senses in contrary and complementary relations, respectively (Brown, p.26), e.g., hot—warm—cold.

The third group of antonyms is based on the oppositeness, where one item presupposes the other, and this oppositeness is called converseness. Some scholars name these types of antonyms relational (Denham & Lobeck, 2010, p. 296; Tserdanelis & Wong, 2004, p.225). Some examples of these antonyms are husband—wife, buy—sell, above –below, over—under, parent-child, teacher—student, doctor—patient, friend—enemy, lawyer—client, day—night, begin—end, and others. There cannot be a husband without a wife or a doctor without a patient, and there cannot be a parent without a child. Converseness presupposes that each antonym describes the same relation or activity from a different side. Reverses are relations between terms describing movement, where one term describes movement in one direction and the other, the same movement, in the opposite direction.

All languages have antonyms, and antonyms share the same types of relation.

7.3 Sense Categories: Hyponymy

The third kind of semantic relation is hyponymy,a relation of inclusion. “A hyponym is a word whose meaning is included, or entailed, in the meaning of a more general word” (Denham & Lobeck, 2010, p.298). Hyponymy may be explained as the relation between specific and general lexemes and phrases; for example, house is a hyponym of building. Georgios Tserdanelis and Wai Yi Peggy Wong view this relation as “the loss of specificity” (2004, p.225). It indicates moving from specific (a rose, tulip, and petunia) to general (flower). The relationship between the lexemes can be seen in the diagram:

Flower and plant are super-ordinate terms, or hypernyms. Flower is the hypernym for crocus, rose, begonia, and daffodil, and it is also a hyponym of plant. Flower is superior to crocus, rose, begonia, and daffodil, but flower is inferior to plant at the same time.

It should be noted that not all lexemes have hypernyms; for example, nightclub or balloon may not have hypernyms other than vague names such as a place and a thing. Sometimes, it is difficult to assign hypernyms to abstract nouns.

Like other semantic relations, hyponymy can be subdivided into two subtypes: taxonomicand functional(Miller, 1998b, as cited in Murphy, p. 219). Taxonomies are classification systems. Taxonomic relation can be illustrated in the following example: cow is in a taxonomic relation to animal, but cow is in a functional relation to livestock (a cow functions as livestock). However, functional relation is not necessarily a logical relation because not every cow is livestock, and not every knife is a weapon.

7.4 Sense Categories: Meronymy

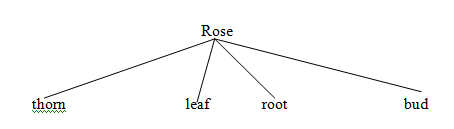

The fourth kind of semantic relation is meronymy (from Greek meros = part and onoma = name), which is the semantic relationship between parts of something to the whole. The ‘part of’ relation can be illustrated in the following diagram:

Thorn, leaf, root, and bud are meronyms of the holonym (Greek holon = whole and onoma = name) rose.

7.5 Related Senses

A traditional distinction is made in lexicology between homonymy and polysemy. Both deal with multiple senses of the same phonological word, but polysemy is invoked if the senses are judged to be related. Lexicographers should keep this in their mind when they design their dictionaries “because polysemous senses are listed under the same lexical entry, while homonymous senses are given separate entries” (Saeed, 2009).

Polysemyis a semantic process whereby a lexeme assumes two or more related meanings (Greek poly = ‘ many’, semy = ‘ meanings’). For example, the lexeme “finger” does not only denote ‘a digit of the hand’ but also ‘the part of a glove, covering one of the fingers’; ‘a hand of a clock’; ‘an index’; and ‘a part in various machines.’ Body parts are often polysemous. we use leg to refer to the leg of a chair and the leg of a table; arm to refer to the arm of a chair; and eye to refer to the eye of a storm. A lexeme that has more than one meaning in the language is polysemous. It is very important to distinguish between the lexical meaning of a lexeme in speech and its semantic structure in the language. The meaning of a lexeme in speech is contextual; therefore, polysemy can exist only in the language, not in speech. The semantic structure of a polysemous word may be defined as a structured set of interrelated meanings. These meanings belong to the same set because they are expressed by a single form. The set is called structured because its elements are interrelated and can be explained by means of one another.

7.6 Unrelated Senses: Homonymy

Words that sound the same but have different (unrelated) meanings are called homonyms (Greek homeos = ‘same’, onoma = ‘name’). Homonyms are either pronounced or spelled like another, or sometimes they are spelled and pronounced alike but have different meanings. Homonyms which are spelled alike but have differences in pronunciation and meaning are called homographs, e.g., bow (a show of respect or submission)—bow (a flexible strip for firing arrows or something bent into a simple curve); lead (position at the front) -- lead (an insulated electrical conductor connected to an electrical device). Homonyms which are pronounced alike but have differences in spelling and meaning are called homophones, e.g., I—eye, knight—night, sole—soul, gorilla—guerilla, to—too—two, bear—bare, brake—break, scent—sent, jeans—genes, waive—wave, buy—bye, and others. Homophones are often the basis for puns, e.g., Seven days without chocolate make one weak. The sign said, “Fine for parking here,” and since it was fine, I parked there. Homonyms which are pronounced and spelled alike but have different meanings are called homonyms proper, e.g. bear (to have children)—bear (tolerate)—bear (to carry)—bear (animal) and tear (to rip)—tear (to fill with tears), and others.

James B. Hobbs, who compiled a dictionary, Homophones and Homograph (1930), differentiates homonyms, homophones, and homographs. He defines homonym as “one of two or more words spelled and pronounced alike but different in meaning” (p.7). Homophone is defined as “one of two or more words pronounced alike but different in meaning or derivation or spelling” (p.7). Homograph is “one of two or more words spelled alike but different in meaning or derivation or pronunciation” (p.7). In his dictionary, Hobbs sharply distinguishes these three categories.

Date: 2015-12-18; view: 1612

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Part V: Word-Formation 2 page | | | Part V: Word-Formation 4 page |