CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Back in Bockhampton

In July 1867, unable to have his poems published and weary of London, Hardy left the capital to return to Bockhampton and resumed working for Hicks. Shortly after his return, Hardy probably entered into a passionate affair with Tryphena Sparks (1851-1890)

an attractive sixteen-year-old cousin. Tryphena was the youngest child of James and Maria Sparks, Hardy’s uncle and aunt, who lived in a thatched cottage in the nearby village of Puddletown. Some biographers believe that in the years 1868 to 1870, when she was a trainee teacher in the Puddletown school, she had a romance with Hardy, although there is too little evidence of their relationship. Nevertheless, Tryphena must have exerted some profound effect on Hardy’s life since she appears in disguise in many of his novels and poems. After her death Hardy wrote a poem pervaded with personal memories, entitled “Thoughts of Phena”. The poem begins with the words: "That no line of her writing have I. Nor a thread of her hair." Hardy goes on to recall her as "my lost prize".

First novels

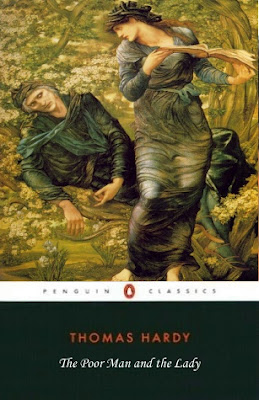

Under the inspiration of George Meredith’s prose. Hardy began to write his first novel The Poor Man and the Lady, which he submitted to the publishing house of Alexander Macmillan

Although Macmillan did not publish it, he encouraged Hardy to keep writing. Meredith advised him to write novels with more plot. In 1869, John Hicks died and Hardy moved to Weymouth to seek employment as an architectural assistant. At the same time he began to write another novel, Desperate Remedies, which was also rejected by Macmillan but published anonymously in three volumes by the publisher William Tinsley in 1871. After the publication of Desperate Remedies, Hardy decided to devote himself fully to writing, although he could not yet achieve a literary or financial success. In 1872, he published his second novel, Under the Greenwood Tree. Encouraged by favourable reception Hardy published A Pair of Blue Eyes (1873), the most autobiographical of all his novels, which introduced some of the themes he would develop in his later works. The fourth novel, Far from the Madding Crowd (1874) gained public notice and eventually brought him financial success. In 1878, The Return of the Native brought Hardy another publishing success. The ensuing years would bring him a constant rise in literary popularity. Hardy set all his novels in the fictional part of south and south-west England which he called Wessex.

Love and marriage

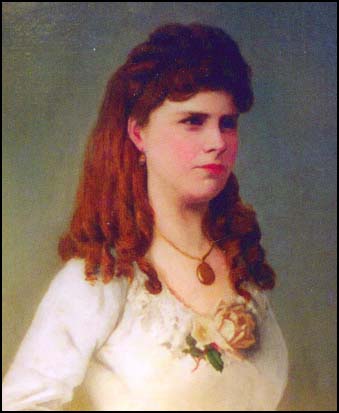

When Hardy was occupied in the restoration of a church in St. Juliot, near the site of the legendary Castle Tintagel, King Arthur’s Camelot in Cornwall in 1870, he met for the first time Emma Lavinia Gifford, the local rector’s sister-in-law.

He was captivated by both her looks and admiration for him. Emma, who was attracted by Hardy’s literary interests, encouraged him to write fiction and poetry. They soon fell in love with each other but waited four years to be married at St Peters Church, Paddington, London, on 17 September 1874. Curiously enough, none of Hardy’s family attended the wedding ceremony, which was performed by Canon Edwin Hamilton Gifford, Emma’s uncle, who later became Archdeacon of London. When they married, they were both thirty years old, but Hardy thought she looked much younger and she thought he looked much older. The first years of their marriage were quite happy. The couple spent their honeymoon in Paris and travelled extensively in England and on the Continent. However, in later years, Emma felt more and more estranged from her husband. She did not entirely approve of the content of his fictions, and last but not least, his romantic attachments to young artistic ladies, such as Florence Henniker, Rosamund Tomson, and Agnes Grove. Emma kept a secret diary in which she recorded her remarks and her complaints about her husband.

Emma Lavinia Gifford

The Twin Riverside Villas. In the yellow house (left) Hardy and his wife Emma lived from 1875 through 1877; it was here, overlooking Sturminstyer-Newton's common, that he wrote The Return of the Native.

Max Gate

In 1885, the couple settled near Dorchester at Max Gate, a large mid-Victorian villa, which Hardy had designed himself where he lived for the rest of his life.

Hardy designed the window of his study at Maxgate so that its central panes would not block his view of the garden. Much of his later poetry was written in this room, the furnishings and books of which are now in the Dorset County Museum, Dorchester.

In 1895-96 and 1907, Hardy made significant extensions and alterations to the house, including enlarging the kitchen and refurbishing his study. Hardy felt extremely comfortable at Max Gate, which he often called his country retreat. In 1886, his second tragic novel, The Mayor of Casterbridge, was published. Its fictional setting resembles old Dorchester, a market town which Hardy knew very well. In 1887, Hardy and his wife Emma took a trip to Italy. They returned to Max Gate via Paris and London. In 1896, Emma introduced Hardy to the new fashionable sport of cycling. Hardy bought himself an expensive Rover Cobb bike, and the couple frequently toured the Dorset countryside. Apart from cycling, Hardy and his wife used to make annual visits to London in spring or summer. They attended theatres, operas, and social gatherings. After spending the summer 1896 in London, the Hardys extended their holidays and visited three English towns: Worcester, Stratford and Dover. Next they went to Belgium. Hardy saw the historic Field of Waterloo, where Napoleon was defeated. He had already made a plan of his epic drama The Dynasts, devoted to the history of Napoleonic wars.

Return to poetry

The publication of Tess of the d’Urbervilles in 1891 shocked and dismayed the Victorian public with its presentation of a young beautiful girl seduced by an aristocratic villain.

Regarding precisely which Marlott cottage had in mind for that occupied by the Durbeyfields at the opening of Tess of the D'Urbervilles, there must have been several other possibilities in the 1890s, but Marnhull is a very small village, and this is the only Elizabethan-period thatched cottage there; coins from the reign of James I were found when the central back entrance was restored a few years ago. although the noted photographer Herman Lea claimed that the original of Tess's cottage was "swept away," in later life Hardy actually came to visit the thatched building known as Barton Cottage "at the head of a narrow, bent cul-de-sac ('a crooked lane or street') off the west side of the B3092, a little north of Walton Elm Cross" ( p. 84). The owner of the house in the 1920s was a Major Campbell-Johnson; according to a tradition that Robinson has recorded.

In order to have the novel published, Hardy made some concessions about its plot; extensive passages were either severely modified or deleted outright. The same happened to his last novel, Jude the Obscure, published in book form in 1895. In 1898, disturbed by the public uproar over the reception of his two greatest novels, Hardy announced that he had ceased to write prose fiction. He returned to poetry, which he regarded as a purer art form than prose fiction. As a young man he could not make enough money to live on by writing poetry, so he had decided to write novels. However, after giving up the novel in adulthood, Hardy published a collection of his earlier poems under the title Wessex Poems (1898).

Between 1903 and 1908 Hardy wrote mostly in blank verse a great panorama of the Napoleonic wars, the epic drama The Dynasts. His literary authority was beyond dispute. In 1905, he was awarded an honorary degree at the University of Aberdeen and recognised as one of the most outstanding British authors. In 1910, King George V conferred on him the Order of Merit, and in 1912 he received the gold medal of the Royal Society of Literature. In 1913, Hardy, who had never graduated from college, received Cambridge honorary degree of Doctor of Letters. His popularity grew immensely and his novels were reprinted, some of them being dramatised and performed on stage. In 1914, the adaptation of The Dynasts was performed at the Kingsway Theatre, London. Between 1911 and 1914 Hardy disposed of most of his manuscripts; some of them were deposited in public libraries and museums, others were purchased, mostly by American dealers and collectors.

Cottage in Marnhull village, Dorset — supposedly the model for Tess Durbeyfield's thatched cottage at Marlott.

Stonehenge

Here at Stonehenge in Wiltshire, Tess is apprehended by the police for the murder of Alec D'Urberville. Hardy chose the setting for the melodramatic climax of Tess of the D'Urbervilles (1891) because of its associations with human sacrifice in Britain's pre-Christian era.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

(ìàëåíüêèå ôîòêè òåññ+ ïîäïèñè)

Date: 2015-12-18; view: 1082

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| Childhood and youth | | | Emma’s death and second marriage |