CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

THE WHISPERING LAND 9 page

"Si, si" said Luna, his dark eyes worried. "I have never seen anyone keep an animal like that. She is half dead."

"I think I can save her," I said. "At least, I think we've got a fifty-fifty * chance."

We drove in silence along the rutted road for some way before Luna spoke.

"Gerry, you do not mind stopping once more, only for a minute!" he inquired anxiously. "It is on our way. I hear of someone else that has a cat they might sell."

"Yes, all right, if it's on the way. But I hope to God it's in better condition than the one we've got."

Presently Luna ran the car off the road on to a sizable stretch of greensward. On one corner of this stood a dilapidated-looking marquee,* and near it a small, battered-looking merry-go-round and a couple of small booths made of striped canvas now so faded as to be almost white. Three fat, glossy horses, one a bright piebald, grazed near by, and around the marquee and the booths trotted a number of well-fed-looking dogs, who had the air of professionals.*

"What is this? It looks like a circus," I said to Luna.

"It is a circus," said Luna, grinning, "only a very small one."

I was amazed that any circus, even a small one, could make a living in a place as remote and small as Oran, but this one appeared to be doing all right for, although the props were somewhat decrepit, the animals looked in good condition. As we left the car a large ginger-haired man appeared, ducking out from under the flap of the marquee. He was a muscular individual with shrewd green eyes and powerful, well-kept hands, who looked

as though he would be capable of doing a trapeze act or a lion act with equal skill. We shook bands, and Luna explained our business.

"Ah, you want my puma," * he grinned. "But I warn you I want a lot of money for her... she's a beauty. But she eats too much, and I can't afford to keep her. Come and see her, she's over here. A real devil, I pan tell you. We can't do a thing with her."

He led us to a large cage in one corner of which crouched a beautiful young puma, about the size of a large dog. She was fat and glossy, and still had her baby paws, which, as in all young cats, look about three times too big for the body. Her coat was a rich amber colour, and her piercing, moody eyes a lovely leaf green. As we approached the cage she lifted one lip and showed her well-developed baby teeth in a scornful snarl. She was simply heavenly, and a joy to look at after the half-starved creature we had just bought, but I knew, fingering my wallet, that I should have to pay a lot for her.

The bargaining lasted for half an hour and was conducted over a glass of very good wine, which the circus proprietor insisted we drank with him. At length I agreed to a price, which, though high, seemed to me to be fair. Then I asked the man if he would keep her until the following day for me, if I paid for her evening meal, for I knew that she would be in good hands, and I had no cage ready for her reception. This our amiable ginger friend agreed to and the bargain was sealed with another glass of wine, and then Luna and I drove back home to try and resurrect the unfortunate ocelot.

When I had built a cage for her, and one of Luna's lesser relatives had appeared with a large sackful of sweet-smelling sawdust, I got the poor creature out of her evil-smelling box and dressed the wound on her thigh. She just lay on the ground apathetically, though the washing of the wound must have hurt considerably. Then I gave her a large shot of penicillin, which again she took no notice of. The third operation was to try and dry her coat out a bit, for she was drenched with her own urine, and already the skin of her belly and paws was fiery red, burnt by the acid. All I could do was literally to cover her in sawdust, rubbing it well into the fur to absorb the moisture, and then gently

dusting it out again. Then I unpicked the more vicious tangles in her fur, and by the time I had finished she had begun to look faintly like an ocelot. But she still lay on the floor, uncaring. I cut the filthy collar away from her neck, and put her in her new cage on a bed of sawdust and straw. Then I placed in front of her a bowl containing one raw egg and a small quantity of finely-minced fresh steak. At first she displayed no interest in this, and my heart sank, for I thought she might well have reached the stage of starvation where no amount of tempting offerings would induce her to eat. In sheer desperation I seized her head and ducked her face into the raw egg, so that she would be forced to lick it off her whiskers. Even this indignity she suffered without complaint, but she sat back and licked the dripping egg off her lips, slowly, carefully, like someone sampling a new, foreign and probably dangerous dish. Then she eyed the dish with a disbelieving look in her eye. I honestly think that the animal, through ill-treatment and starvation, had got into a trance-like state, where she disbelieved the evidence of her own senses. Then, while I held my breath, she leant forward and lapped experimentally at the raw egg. Within thirty seconds the plate was clean, and Luna and I were dancing a complicated tango of delight round the patio, to the joy of his younger relatives.

"Give her some more, Gerry," panted Luna, grinning from ear to ear.

"No, I daren't," I said. "When a creature's that bad,* you can kill it from overfeeding. She can have a bowl of milk later on, and then tomorrow she can have four small meals during the day. But I think she'll be all right now."

'That man was a devil," said Luna shaking his head.

I drew a deep breath and, in Spanish, gave him my views on the cat's late owner.

"I never-knew you knew so many bad things in Spanish, Gerry," said Luna admiringly. "There was one word you used I have never heard before."

"I've had some good teachers," I explained.

"Well, I hope you say nothing like that tonight," said Luna, his eyes gleaming.

"Why? What's happening tonight?"

"Because we are leaving tomorrow for Calilegua my friends have made an asado in your honour, Gerry. They will play and sing only very old Argentine folk-songs so that you may record them on your machine. You like this idea?" he asked anxiously.

"There is nothing I like better than an asado," I said, "and an asado with folk-songs is my idea of Heaven."

So, at about ten o'clock that evening, a friend of Luna's picked us up in his car and drove us out to the estate, some distance outside Oran, where the asado had been organised. The asado ground was a grove near the estancia, an area of bare earth that told of many past dances, surrounded by whispering eucalyptus trees and massive oleander bushes. The long wooden benches and trestle-tables * were lit with the soft yellow glow of half a dozen oil-lamps, and outside this buttercup circle of light the moonlight was silver brilliant. There were about fifty people there, many of whom I had never met, and few of them over the age of twenty. They greeted us uproariously, almost dragged us to the trestle-tables which were groaning under the weight of food, and placed great hunks of steak, crisp and sizzling from the open fires, in front of us. The wine-bottles passed with monotonous regularity, and within half-an-hour Luna and I were thoroughly in the party spirit, full of good food, warmed with red wine. Then these gay, pleasant young people gathered round while I got the recorder ready, watching with absorbed attention the mysteries of threading tape and getting levels. When, at last, I told them I was ready, guitars, drums and flutes appeared as if by magic, and the entire crowd burst into song. They sang and sang, and each time they came to the end of a song, someone would think of a new one, and they would start again. Sometimes a shy, grinning youth would be pushed to the front of the circle as the only person there capable of rendering a certain number, and after much encouragement and shouts of acclamation he would sing. Then it would be a girl's turn to sing the solo refrain in a sweet-sour voice, while the lamps glinted on her dark hair, and the guitars shuddered and trembled under the swiftly-moving brown fingers of their owners. They danced in a row on a flagstoned path, their spurs ringing sparks from the stone, so that I could record the heel-taps *

which are such an intricate part of the rhythm of some of their songs; they danced the delightful handkerchief dance with its pleasant lilting tune, and they danced tangos that made you wonder if the stiff, sexless dance called by that name in Europe was a member of the same family. Then, shouting with laughter because my tapes had run out and I was in despair, they rushed me to the table, plied me with more food and wine, and sitting round me sang more sweetly than ever. These, I say again, were mostly teenagers, revelling in the old and beautiful songs of their country, and the old and beautiful dances, their faces flushed with delight at my delight, honouring a stranger they had never seen before and would probably never see again.

By now they had reached the peak. Slowly they started to relax, the songs getting softer and softer, more and more plaintive, until we all reached the moment when we knew the party was over, and that to continue it longer would be a mistake. They had sung themselves from the heavens back to earth,* like a flock of descending larks. Flushed, bright-eyed, happy, our young hosts insisted that we travelled back to Oran with them in the big open back of the lorry in which they had come. We piled in, our tightly-packed bodies creating a warmth for which we were grateful, for the night air was now chilly. Then as the lorry roared off down the road to Oran, bottles of red wine were passed carefully from hand to hand, and the guitarists started strumming. Everybody, revived by the cool night air, took up the refrain, and we roared along through the velvet night like a heavenly choir. I looked up and saw the giant bamboos that curved over the road, now illuminated by the lorry's headlights. They looked like the talons of some immense green dragon, curved over the road, ready to pounce if we stopped singing for an instant. Then a bottle of wine was thrust into my hand, and as I tipped my head back to drink I saw that the dragon had passed, and the moon stared down at me, white as a mushroom-top against the dark sky.

Chapter Seven

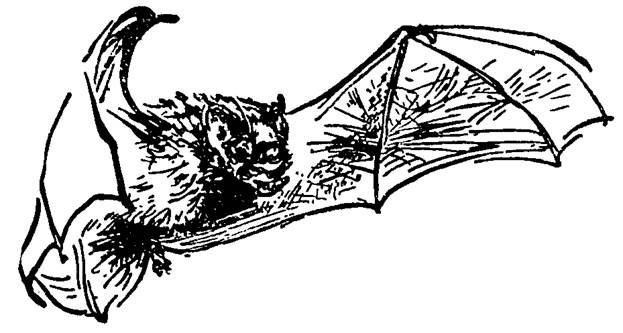

VAMPIRES * AND WINE

The vampire bat is often the cause of much trouble, by biting the horses on their withers.

CHARLES DARWIN: The Voyage of H. M. S. Beagle

On my return from Oran the garage almost overflowed with animals. One could scarcely make oneself heard above the shrill, incomprehensible conversations of the parrots, the harsh rattling cries of the guans, the incredibly loud trumpeting of the seriemas, the chattering of the coatimundis, and an occasional dull rumble, as of distant thunder, from the puma, whom I had christened Luna in the human Luna's honour. As a background to this there was a steady scrunching noise that came from the agouti cage, for it was always engaged in trying to do alterations to its living quarters with its chisel-like teeth.

As soon as I had got back I had begun constructing cages for all our various creatures, leaving the caging of Luna until last, for she had travelled in a large packing-case that gave her more than enough room to move about in. However, when all the other animals were housed, I set about building a cage worthy of the puma, which, I hoped, would show off her beauty and grace. I had just finished it when Luna's godfather * arrived, singing lustily as usual, and offered to help me in the tricky job of getting Luna to pass from her present quarters into the new cage. We carefully closed the garage doors so that, if anything untoward happened, the cat would not go rampaging off across the countryside and be lost. It also had the advantage, as the human Luna pointed out, that we would be locked in with her, a prospect he viewed with alarm and despondency. I soothed his fears by telling him that the puma would be far more frightened than we were, and at that moment she uttered a rumbling growl of such malignance and fearlessness that Luna paled visibly. My attempt to persuade him that this growl was really an indication of how afraid the animal was of us was greeted with a look of complete disbelief.

The plan of campaign was that the crate in which the puma now reposed would be dragged opposite the door of the new cage, a few slats removed from the side, and the cat would then walk from the crate into the cage without fuss. Unfortunately owing to the somewhat eccentric construction of the cage I had built, we could not wedge the crate close up to the door: there was a gap of some eight inches between crate and cage. Undeterred, I placed planks so that they formed a sort of short tunnel between the two boxes, and then proceeded to remove the end of the crate so that the puma could get out. During this process a golden paw, that appeared to be the size of a ham, suddenly appeared in the gap and a nice, deep slash appeared across the back of my hand.

"Ah!" said Luna gloomily, "you see, Gerry?"

"It's only because she's scared of the hammering," I said with feigned cheerfulness sucking my hand. "Now, I think I've removed enough boards for her to get through. All we have to do is wait."

We waited. After ten minutes I peered through a knot hole and saw the wretched puma lying quietly in her

crate, drowsing peacefully, and showing not the slightest interest in passing down our rickety tunnel and into her new and more spacious quarters. There was obviously only one thing to do, and that was to frighten her into passing from crate to cage. I lifted the hammer and brought it down on the back of the crate with a crash. Perhaps I should have warned Luna. Two things happened at once. The puma, startled out of her half-sleep, leapt up and rushed to the gap in the crate, and the force of my blow with the hammer knocked down the piece of board which was forming Luna's side of the tunnel. In consequence he looked down just in time to see an extremely irritable-looking puma sniffing meditatively at his legs. He uttered a tenor screech, which I have rarely heard equalled, and leapt vertically into the air. It was the screech that saved the situation. It so unnerved the puma that she fled into the new cage as fast as she could, and I dropped the sliding door, locking her safely inside. Luna leant against the garage door wiping his face with a handkerchief.

"There you are," I said cheerfully, "I told you it would be easy."

Luna gave me a withering look. "You have collected animals in South America and Africa?" he inquired at length. "That is correct?" "Yes."

"You have been doing this work for fourteen years?" "Yes."

"You are now thirty-three?" "Yes."

Luna shook his head, like a person faced with one of the great enigmas of life.

"How you have lived so long only the good God knows," he said.

"I lead a charmed * life," I said. "Anyway, why did you come to see me this morning, apart from wanting to wrestle with your namesake?"

"Outside," said Luna, still mopping his face, "is an Indian with a bicho. I found him with it in the village." "What kind of bicho?" I asked as we left the garage and went out into the garden.

"I think it is a pig," said Luna, "but it's in a box and I can't see it very clearly."

The Indian was squatting on the lawn, and in front of him was a box from which issued a series of falsetto squeaks and muffled grunts. Only a member of the pig family could produce such extraordinary sound. The Indian grinned, removed his big straw hat, ducked his head, and then, removing the lid of the box, drew forth the most adorable little creature. It was a very young collared peccary,* the common species of wild pig that inhabits the tropical portions of South America.

"This is Juanita," said the Indian, smiling as he placed the diminutive creature on the lawn, where it uttered a shrill squeak of delight and started to snuffle about hopefully.

Now, I have always had a soft spot for the pig family,* and baby pigs I cannot resist, so within five minutes Juanita was mine at a price that was double what she was worth, speaking financially, but only a hundredth part of what she was worth in charm and personality. She was about eighteen inches long and about twelve inches high, clad in long, rather coarse greyish fur, and a neat white band that ran from the angle of her jaw up round her neck, so that she looked as though she was wearing an Eton collar.* She had a slim body, with a delicately tapered snout ending in a delicious retrousse * nose (somewhat like a plunger), and slender, fragile legs tipped with neatly polished hooves the circumference of a sixpence. She had a dainty, lady-like walk, moving her legs very rapidly, her hooves making a gentle pattering like rain.

She was ridiculously tame, and had the most endearing habit of greeting you — even after only five minutes' absence — as if you had been away for years, and that, for her, these years had been grey and empty. She would utter strangled squeaks of delight, and rush towards you, to rub her nose and behind against your legs in an orgy of delighted reunion, giving seductive grunts and sighs. Her idea of Heaven was to be picked up and held on her back in your arms, as you would nurse a baby, and then have her tummy scratched. She would lie there, her eyes closed, gnashing her baby teeth together, like miniature castanets, in an ecstasy of delight. I still had all the very tame and less destructive creatures funning loose in the garage, and as Juanita behaved in such

a lady-like fashion I allowed her the run of the place * as well, only shutting her in a cage at night. At feeding time it was a weird sight to see Juanita, her nose buried in a large dish of food, surrounded by an assortment of creatures — seriemas parrots, pigmy rabbits, guans — all trying to feed out of the same dish. She always behaved impeccably, allowing the others plenty of room to feed, and never showing any animosity, even when a wily seriema pinched titbits from under her pink nose. The only time I ever saw her lose her temper was when one of the more weak-minded of the parrots, who had worked himself into a highly excitable state at the sight of the food plate, flew down squawking joyously, and landed on Juanita's snout. She shook him off with a grunt of indignation and chased him, squawking and fluttering, into a corner, where she stood over him for a moment, champing her teeth in warning, before returning to her interrupted meal.

When I had got all my new specimens nicely settled, I paid a visit to Edna to thank her for the care and attention she had lavished on my animals in my absence. I found her and, Helmuth busy with a huge pile of tiny scarlet peppers, with which they were concocting a sauce of Helmuth's invention, an ambrosial * substance which, when added to soup, removed the roof of your mouth with the first swallow, but added a flavour that was out of this world.* An old boot, I am sure, boiled and then covered with Helmuth's sauce, would have been greeted with shouts of joy by any gourmet.*

"Ah, Gerry," said Helmuth, rushing to the drink cupboard. "I have got good news for you."

"You mean you've bought a new bottle of gin?" I inquired hopefully.

"Well, that of course," he said grinning. "We knew you were coming hack. But apart from that do you know that next week-end is a holiday?"

"Yes, what about it?"

"It means," said Helmuth, sloshing gin into glasses with gay abandon, "that I can take you up the mountains of Calilegua for three days. You like that, eh?"

I turned to Edna.

"Edna,"I began, "I love you..."

"All right," she said resignedly, "but you must make sure * the puma can't get out, that is all I insist upon." So, the following Saturday morning, I was awoken, just as dawn was lightening the sky, by Luna, leaning through my window and singing a somewhat bawdy love-song. I crawled out of bed, humped my equipment on to my back, and we made our way through the cool, aquarium light of dawn to Helmuth's flat. Outside it was a group of rather battered-looking horses, each clad in the extraordinary saddle that they use in the north of Argentina. The saddle itself had a deep, curved seat with a very high pommel in front, so that it was almost like an armchair to sit in. Attached to the front of the saddle were two huge pieces of leather, shaped somewhat like angel's wings which acted as wonderful protection for your legs and knees when you rode through thorn scrub. In the dim dawn light the horses, clad in their weird saddles, looked like some group of mythical beasts, Pegasus * for example, grazing forlornly on the dewy grass. Nearby lounged a group of four guides and hunters who were to accompany us, delightfully wild and unshaven-looking, wearing dirty bombachas, great wrinkled boots and huge, tattered straw hats. They were watching Helmuth, his corn-red hair gleaming with dew, as he rushed from horse to horse, stuffing various items into the sacks, which were slung across the saddles. These sacks, Helmuth informed me, contained our rations for the three days we should be away. Peering into two of the sacks I discovered that our victuals consisted mainly of garlic and bottles of red wine, although one sack was stuffed with huge slabs of unhealthy-looking meat, the blood from which was dripping through the sacking, and whose curious shape gave one the rather unpleasant impression that we were transporting a dismembered body. When everything was to Helmuth's satisfaction, Edna came out, shivering in her dressing gown, to see us off, and we mounted our bony steeds * and set off at a brisk trot towards the mountain range which was our goal, dim, misty and flecked here and there with gold and green in the morning light.

At first we rode along the rough tracks that ran through the sugar-cane fields, where the canes whispered and clacked in the slight breeze. Our hunters and guides had

cantered on ahead, and Luna and I and Helmuth rode in a row, keeping our horses at a gentle walk, Helmuth was telling me the story of his life, how at the age of seventeen (as an Austrian) he had been press-ganged * into the German Army, and had fought through the entire war, first in North Africa, then Italy and finally in Germany, without losing anything except the top joint of one finger, which was removed by a land-mine that blew up under him and should have killed him. Luna merely slouched in his great saddle, like a fallen puppet, singing softly to himself. When Helmuth and I had settled world affairs generally, and come to the earth-shaking * conclusion that war was futile we fell silent and listened to Luna's soft voice, the chorus of canes, and the steady clop of our horses' hooves, like gentle untroubled heart-beats in the fine dust.

Presently the path left the cane fields and started to climb up the lower slopes of the mountain, passing into real forest. The massive trees stood, decorated with trailing epiphytes * and orchids,* each one bound to its fellow by tangled and twisted lianas, * like a chain of slaves. The path had now taken on the appearance of an old watercourse (and in the rainy season I think this is what it must have been) strewn with uneven boulders of various sizes, many of them loose. The horses, though used to the country and sure-footed,* frequently stumbled and nearly pitched you over their heads, so you had to concentrate on holding them up unless you suddenly wanted to find yourself with a split skull. The path had now narrowed, and twisted and turned through the thick undergrowth so tortuously that, although the three of us were riding almost nose to tail, we frequently lost sight of each other, and if it had not been for Luna's voice raised in song behind me, and the occasional oaths from Helmuth when his horse stumbled, I could have been riding alone. We had been riding this way for an hour or so, occasionally shouting Comments or questions to each other, when I heard a roar of rage from Helmuth, who was a fair distance ahead. Rounding the corner I saw what was causing his rage.

The path at this point had widened, and along one side of it ran a rock-lined ravine, some six feet deep. Into this one of our pack horses had managed to fall, by

some extraordinary means known only to itself, for the path at this point was more than wide enough to avoid such a catastrophe. The horse was standing, looking rattier smug I thought, in the bottom of the ravine, while our wild-looking hunters had dismounted and were trying to make it climb up on to the path again. The whole of one side of the horse was covered with a scarlet substance that dripped macabrely,* and the animal was standing in what appeared to be an ever-widening pool of blood. My first thought was to wonder, incredulously, how the creature had managed to hurt itself so badly with such a simple fall, and then I realised that the pack that the horse was carrying contained, among other things, part of our wine supply. The gooey * mess and Helmuth's rage were explained. We eventually got the horse back up to path, and Helmuth peered into the wine-stained sack, uttering moans of anguish.

"Bloody horse," he said, "why couldn't it fall on the other side, where the meat is?"

"Anything left?" I asked. "No," said Helmuth, giving me an anguished look, "every bottle broken. Do you know what that means, eh?"

"No," I said truthfully. "It means we have only twenty-five bottles of wine to last us," said Helmuth. Subdued by this tragedy we proceeded on our way slowly. Even Luna seemed affected by our loss, and sang only the more mournful songs in his extensive repertoire.

We rode on and on and on, the path getting steeper and steeper. At noon we dismounted by a small, tumbling stream, our shirts black with sweat, bathed our-selves and had a light meal of raw garlic, bread and wine. This, to the fastidious, may sound revolting, but when you are hungry there is no finer combination of tastes. We rested for an hour, to let our sweat-striped horses dry off, and then mounted again and rode on throughout the afternoon; At last, when the evening shadows were lengthening and we could see glimmers of a golden sunset through tiny gaps in the trees above, the path suddenly flattened out, and we rode into a flat, fairly clear area of forest. Here we found that our hunters had already dismounted and unsaddled the horses, while one of them

had gathered dry brushwood and lighted a fire. We dismounted stiffly, unsaddled our horses and then, using our saddles and woolly sheepskin saddle-cloth, called a recado, as back-rests we relaxed round the fire for ten minutes, while the hunters dragged out some of the unsavoury-looking meat from the sacks and set it to roast on wooden spits.

Presently, feeling a bit less stiff, and as there was still enough light left, I decided to have a walk round the forest in the immediate area of our camp. Very soon the gruff voices of the hunters were lost among the leaves as I ducked and twisted my way * through the tangled, sunset-lit undergrowth. Overhead an occasional humming-bird flipped and purred in front of a flower for a last-night drink, and small groups of toukans * flapped from tree to tree, yapping like puppies, or contemplating me with heads on one side; wheezing like rusty hinges. But it was not the birds that interested me so much as the extraordinary variety of fungi * that I saw around me. I have never, in any part of the world, seen such a variety of mushrooms and toadstools littering the forest floor, the fallen tree-trunks, and the trees themselves. They were in all colours, from wine-red to black, from yellow to grey, and in a fantastic variety of shapes. I walked slowly for about fifteen minutes in the forest, and in that time I must have covered an area of about an acre. Yet in that short time, and in such a limited space, I filled my hat with twenty-five different species of fungi. Some were scarlet, shaped like goblets of Venetian glass * on delicate stems; others were filigreed with holes, so that they were like little carved ivory tables in yellow and white; others were like great, smooth blobs of tar or lava, black and hard, spreading over the rotting logs, and others appeared to have been carved out of polished chocolate, branched and twisted like clumps of miniature stag's antlers. Others stood in rows, like red or yellow or brown buttons on the shirt-fronts of the fallen trees, and others, like old yellow sponges, bung from the branches, dripping evil yellow liquid. It was a Macbeth witches' landscape,* and at any moment you expected to see some crouched and wrinkled old hag with a basket gathering this rich haul of what looked like potentially poisonous fungi.

Date: 2015-12-11; view: 856

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| THE WHISPERING LAND 8 page | | | THE WHISPERING LAND 10 page |