CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Edit] Scientific illustrations and work in mycology

Beatrix Potter

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

This article is about the author. For the sociologist and reformer born Beatrice Potter, see Beatrice Webb.

| Beatrix Potter | |

Beatrix Potter Beatrix Potter

| |

| Born | Helen Beatrix Potter 28 July 1866 Kensington, London, England, UK |

| Died | 22 December 1943(1943-12-22) (aged 77) Near Sawrey, Lancashire, England, UK |

| Occupation | Children's author and illustrator |

| Genres | Children's literature |

| Notable work(s) | The Tale of Peter Rabbit |

| Spouse(s) | William Heelis |

Helen Beatrix Potter (28 July 1866 – 22 December 1943) was an English author, illustrator, natural scientist and conservationist best known for her imaginative children’s books featuring animals such as those in The Tale of Peter Rabbit which celebrated the British landscape and country life.

Born into a privileged Unitarian family, Potter, along with her younger brother, Walter Bertram (1872–1918), grew up with few friends outside her large extended family. Her parents were artistic, interested in nature and enjoyed the countryside. As children, Beatrix and Bertram had numerous small animals as pets which they observed closely and drew endlessly. Summer holidays were spent in Scotland and in the English Lake District where Beatrix developed a love of the natural world which was the subject of her painting from an early age.

She was educated by private governesses until she was eighteen. Her study of languages, literature, science and history was broad and she was an eager student. Her artistic talents were recognized early. Although she was provided with private art lessons, Potter preferred to develop her own style, particularly favouring watercolour. Along with her drawings of her animals, real and imagined, she illustrated insects, fossils, archeological artefacts, and fungi. In the 1890s her mycological illustrations and research on the reproduction of fungi spores generated interest from the scientific establishment. Following some success illustrating cards and booklets, Potter wrote and illustrated The Tale of Peter Rabbit publishing it first privately in 1901, and a year later as a small, three-colour illustrated book with Frederick Warne & Co. She became unofficially engaged to her editor Norman Warne in 1905 despite the disapproval of her parents, but he died suddenly a month later, of leukemia.[1]

With the proceeds from the books and a legacy from an aunt, Potter bought Hill Top Farm in Near Sawrey, a tiny village in the English Lake District near Ambleside in 1905. Over the next several decades, she purchased additional farms to preserve the unique hill country landscape. In 1913, at the age of 47, she married William Heelis, a respected local solicitor from Hawkshead. Potter was also a prize-winning breeder of Herdwick sheep and a prosperous farmer keenly interested in land preservation. She continued to write, illustrate and design spin-off merchandise based on her children’s books for Warne until the duties of land management and diminishing eyesight made it difficult to continue. Potter published over twenty-three books; the best known are those written between 1902 and 1922. She died on 22 December 1943 at her home in Near Sawrey at age 77, leaving almost all her property to the National Trust. She is credited with preserving much of the land that now comprises the Lake District National Park.

Potter’s books continue to sell throughout the world, in multiple languages. Her stories have been retold in song, film, ballet and animation.

Contents

[hide]

|

Edit] Biography

Edit] Early life

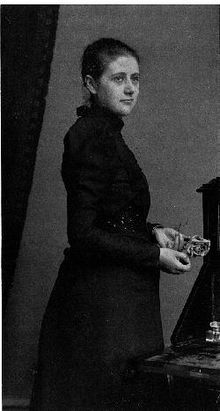

Potter at fifteen years with her springer spaniel, Spot

Potter’s family on both sides was from the Manchester area.[2] They were English Unitarians,[3] a dissenting Protestant sect who rejected the doctrine of the Trinity and were socially and politically discriminated against. Potter’s paternal grandfather, Edmund Potter, from Glossop in Derbyshire, owned the largest calico printing works in England at the time, and later served as a Member of Parliament.[4] Beatrix’s father, Rupert William Potter (1832–1914), was educated in Manchester and trained as a barrister in London. He married Helen Leech (1839–1932), the daughter of another wealthy cotton merchant and shipbuilder from Stalybridge, at Gee Cross on 8 August 1863. Rupert practiced law, specialising in equity law and conveyancing. They lived comfortably at 2 Bolton Gardens, South Kensington, where Helen Beatrix was born on 28 July 1866 and her brother Walter Bertram on 14 March 1872.[5] Both parents were artistically talented,[6] and Rupert was an adept amateur photographer.[7] Rupert had invested in the stock market and by the early 1890s was extremely wealthy.[8]

Beatrix was educated by three able governesses, the last of whom was Annie Moore (née Carter), just three years older than Beatrix, who tutored Beatrix in German as well as acting as lady's companion.[9] She and Beatrix remained friends throughout their lives and Annie's eight children were the recipients of many of Potter’s delightful picture letters. It was Annie who later suggested that these letters might make good children’s books.[10]

In their school room Beatrix and Bertram kept a variety of small pets, mice, rabbits, a hedgehog, some bats along with collections of butterflies and other insects which they drew and studied.[11] There is no evidence to support claims that any of these creatures were mistreated, or that the motive for their study was anything more sinister than natural curiosity and a desire to draw from life. Quite the contrary, Beatrix was devoted to the care of her small animals, often taking them with her on long holidays.[12]

For most of the first fifteen years of her life, Beatrix spent summer holidays at Dalguise, an estate on the River Tay in Perthshire, Scotland. There she sketched and explored an area that nourished her imagination and her observation.[13] Beatrix and her brother were allowed great freedoms in the country and both children became adept students of natural history. In 1887, when Dalguise was no longer available, the Potters took their first summer holiday in Lancashire in the Lake District, at Wray Castle near Windermere.[14] As a result, Beatrix came to meet Hardwicke Rawnsley, incumbent vicar at Wray and later the founding secretary of the National Trust, whose interest in the countryside and country life inspired the same in Beatrix and who was to have a lasting impact on her life.[15][16]

About the age of 14 Beatrix, like many girls at the time, began to keep a diary. Beatrix's was written in a code of her own devising which was a simple letter for letter substitution. Her Journal was an important laboratory for her creativity serving as both sketchbook and literary experiment where in tiny handwriting she reported on society, recorded her impressions of art and artists, recounted stories, and observed life around her.[17] The Journal, decoded and transcribed by Leslie Linder in 1958, does not provide an intimate record of her personal life, but it is an invaluable source for understanding a vibrant part of British society in the late 19th century. It describes Potter’s maturing artistic and intellectual interests, her often amusing insights on the places she visited, and her unusual ability to observe nature and to describe it. Begun in 1881, her journal ends in 1897 when her artistic and intellectual energies were absorbed in scientific study and in efforts to publish her drawings.[18] Precocious but reserved and often bored, she was searching for more independent activities and a desire to earn some money of her own whilst dutifully taking care of her parents, dealing with her especially demanding mother,[19] and managing their various households.

edit] Scientific illustrations and work in mycology

Beatrix Potter’s parents did not discourage higher education. As was common in the Victorian era, women of her class were privately educated and rarely sent to college.[20]

Beatrix Potter was interested in every branch of natural science save astronomy.[21] Botany was a passion for most Victorians and nature study was a popular enthusiasm. Potter was eclectic in her tastes; collecting fossils,[22] studying archeological artifacts from London excavations, and interested in entomology. In all of these areas she drew and painted her specimens with increasing skill. By the 1890s her scientific interests centred on mycology. First drawn to fungi because of their colours and evanescence in nature and her delight in painting them, her interest deepened after meeting Charles McIntosh, a revered naturalist and mycologist during a summer holiday in Perthshire in 1892. He helped improve the accuracy of her illustrations, taught her taxonomy, and supplied her with live specimens to paint during the winter. Curious as to how fungi reproduced Potter began microscopic drawings of fungi spores (the agarics) and in 1895 developed a theory of their germination.[23] Through the aegis of her scientific uncle, Sir Henry Enfield Roscoe, a chemist and vice chancellor of the University of London, she consulted with botanists at Kew Gardens, convincing George Massee of her ability to germinate spores and her theory of hybridisation.[24] She did not believe in the theory of symbiosis proposed by Simon Schwendener, the German mycologist as previously thought, rather she proposed a more independent process of reproduction.[25]

Rebuffed by William Thiselton-Dyer, the Director at Kew, because of her gender and her amateur status, Beatrix wrote up her conclusions and submitted a paper On the Germination of the Spores of the Agaricineae to the Linnean Society in 1897. It was introduced by Massee because, as a female, Potter could not attend proceedings or read her paper. She subsequently withdrew it realising that some of her samples were contaminated, but continued her microscopic studies for several more years. Her paper has only recently been rediscovered, along with the rich, artistic illustrations and drawings that accompanied it. Her work is only now being properly evaluated.[26][27][28] Potter later gave her other mycological drawings and scientific drawings to the Armitt Museum and Library in Ambleside where mycologists still refer to them to identify fungi. There is also a collection of her fungi paintings at the Perth Museum and Art Gallery in Perth, Scotland donated by Charles McIntosh. In 1967 the mycologist W.P.K. Findlay included many of Potter’s beautifully accurate fungi drawings in his Wayside & Woodland Fungi, thereby fulfilling her desire to one day have her fungi drawings published in a book.[29] In 1997 the Linnean Society issued a posthumous apology to Potter for the sexism displayed in its handling of her research.[30]

Date: 2015-12-11; view: 934

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| | | Edit] Artistic and literary career |