CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

FROM THE PAGES OF PYGMALION AND THREE OTHER PLAYS

I am, and have always been, and shall now always be, a revolutionary writer, because our laws make law impossible; our liberties destroy all freedom; our property is organized robbery; our morality is an impudent hypocrisy; our wisdom is administered by inexperienced or malexperienced dupes, our power wielded by cowards and weaklings, and our honor false in all its points. I am an enemy of the existing order for good reasons. (from Shaw’s preface to Major Barbara, pages 43 — 44)

“He knows nothing; and he thinks he knows everything. That points clearly to a political career.” (from Major Barbara, page 127)

“You have learnt something. That always feels at first as if you had lost something.” (from Major Barbara, page 132)

If you cannot have what you believe in you must believe in what you have. (from Shaw’s preface to The Doctor’s Dilemma, page 166)

“I find that the moment I let a woman make friends with me, she becomes jealous, exacting, suspicious, and a damned nuisance. I find that the moment I let myself make friends with a woman, I become selfish and tyrannical. Women upset everything.” (from Pygmalion, page 394)

“The great secret, Eliza, is not having bad manners or good manners or any other particular sort of manners, but having the same manner for all human souls: in short, behaving as if you were in Heaven, where there are no third-class carriages, and one soul is as good as another.” (from Pygmalion, pages 451 -452)

“The surest way to ruin a man who doesn’t know how to handle money is to give him some.” (from Heartbreak House, page 568)

“His heart is breaking: that is all. It is a curious sensation: the sort of pain that goes mercifully beyond our powers of feeling. When your heart is broken, your boats are burned: nothing matters any more. It is the end of happiness and the beginning of peace.” (from Heartbreak House, page 596)

GEORGE BERNARD SHAW

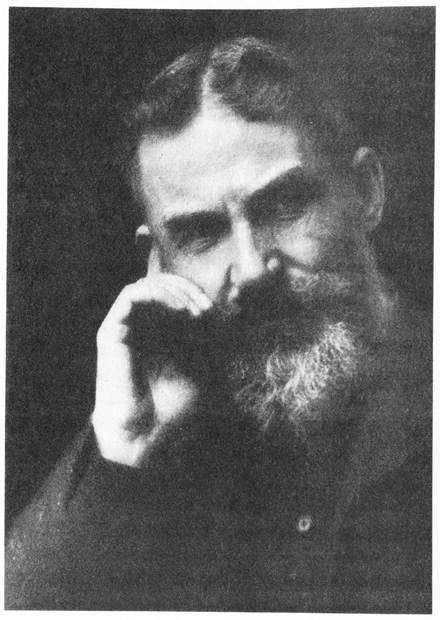

Dramatist, critic, and social reformer George Bernard Shaw was born on July 26, 1856, into a poor yet genteel Dublin household. His diffident and impractical father was an alcoholic disdained by his mother, a professional singer who ingrained in her only son a love of music, art, and literature. Just shy of his seventeenth birthday, Shaw joined his mother and two sisters in London, where they had settled three years earlier. There he struggled — and failed — to support himself by writing. He first wrote a string of novels, beginning with the semi autobiographical Immaturity, completed in 1879. Though some of his novels were serialized, none met with great success, and Shaw decided to abandon the form in favor of drama. While he struggled artistically, he flourished politically; for some years his greater fame was as a political activist and pamphleteer. A stammering, shy young man, Shaw nevertheless joined in the radical politics of his day. In the late 1880s he became a leading member of the fledgling Fabian Society, a group dedicated to progressive politics, and authored numerous pamphlets on a range of social and political issues. He often mounted a soapbox in Hyde Park and there developed the enthralling oratory style that pervades his dramatic writing. In the 1890s, deeply influenced by the dramatic writings of Henrik Ibsen, Shaw spurned the conventions of the stage in “unpleasant” plays, such as Mrs. Warren’s Profession, and in “pleasant” ones like Arms and the Man and Candida. His drama shifted attention from romantic travails to the great web of society, with its hypocrisies and other ills. The burden of writing seriously strained Shaw’s health; he suffered from chronic migraine headaches. Shaw married fellow Fabian and Irish heiress Charlotte Payne-Townshend. By the turn of the century, Shaw had matured as a dramatist with the historical drama Caesar and Cleopatra, and his master-pieces Man and Superman and Major Barbara. In all, he wrote more than fifty plays, including his antiwar Heartbreak House and the polemical Saint Joan, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize. Equally prolific in his writings about music and theater, Shaw was so popular that he signed his critical pieces with simply the initials GBS. (He disliked his first name, George, and never used it except for the initial.) He remained in the public eye throughout his final years, writing controversial plays until his death. George Bernard Shaw died at his country home on November 2, 1950.

THE WORLD OF GEORGE BERNARD SHAW AND HIS PLAYS

1856 — George Bernard Shaw is born on July 26, at 33 Upper Synge Street in Dublin, to George Carr Shaw and Lucinda Elizabeth Gurly Shaw. 1865 — George John Vandeleur Lee, Mrs. Shaw’s singing instructor, moves into the Shaw household. Known as Vandeleur Lee, he has a reputation as an unscrupulous character.

1869 — Embarrassed by controversy and gossip related to his mother’s relationship with Vandeleur Lee, young “Sonny,” as Shaw was called by his family, leaves school.

1871 — He begins work in a Dublin land agent’s office.

1873 — Shaw’s mother, now a professional singer, follows Vandeleur Lee to London, where they establish a household that includes Shaw’s sisters, Elinor Agnes and Lucille Frances (Lucy). Shaw’s mother tries to earn a living per forming and teaching Vandeleur Lee’s singing method.

1876 — Elinor Agnes dies on March 27. Shaw joins his mother, his sister Lucy, and Vandeleur Lee in London. Although he tries to support himself as a writer, for the next five years Shaw remains financially dependent on his mother.

1877 — Shaw ghostwrites music reviews that appear under Vandeleur Lee’s byline in his column for the Hornet, a London newspaper. This first professional writing “job” lasts until the editor discovers the subterfuge.

1879 — Shaw completes and serializes his first novel, Immaturity. He works for the Edison Telephone Company and later will record his experience in his second novel, The Irrational Knot. Henrik Ibsen’s play A Doll’s House premieres.

1880 — Shaw completes The Irrational Knot.

1881 — He becomes a vegetarian in the hope that the change in his diet will relieve his migraine headaches. He completes Love Among Artists. The Irrational Knot is serialized in Our Corner, a monthly periodical.

1882 — Shaw hears Henry George’s lecture on land nationalization, which inspires some of his socialist ideas. He attends meetings of the Social Democratic Federation and is introduced to the works of Karl Marx.

1883 — The Fabian Society — a middle-class socialist debating group advocating progressive, nonviolent reform rather than the revolution supported by the Social Democratic Federation — is founded in London. Shaw completes the novel Cashel Byron’s Profession, drawing on his experience as an amateur boxer. He writes his final novel, An Unsocial Socialist.

1884 — Shaw joins the fledgling Fabian Society; he contributes to many of its pamphlets, including The Fabian Manifesto (1884), The Impossibilities of Anarchism (1893), and Socialism for Millionaires (1901), and begins speaking publicly around London on social and political issues. An Unsocial Socialist is serialized in the periodical Today.

1885 — The author’s father, a longtime alcoholic, dies; neither his estranged wife nor his children attend his funeral. Shaw himself never drinks or smokes. He begins writing criticism of music, art, and literature for the Pall Mall Gazette, the Dramatic Review, and Our Corner. Cashel Byron’s Profession is serialized in the periodical Today.

1886 — Shaw begins writing art and music criticism for the World. Cashel Byron’s Profession is published.

1887 — Swedish dramatist and writer August Strindberg’s play The Father is performed. The Social Democratic Federation’s planned march on Trafalgar Square ends in bloodshed as police suppress the protesters; Shaw is a speaker at the event. His novel An Unsocial Socialist is published in book form.

1888 — Shaw begins writing music criticism in the Star under the pen name Corno di Bassetto (“basset horn,” perhaps a reference to the pitch of his voice).

1889 — He edits the volume Fabian Essays in Socialism, to which he contributes “The Economic Basis of Socialism” and “The Transition to Social Democracy.”

1890 — Ibsen completes Hedda Gabler.

1891 — Ibsen’s Ghosts is performed in London. Shaw publishes The Quintessence of Ibsenism, a polemical pamphlet that celebrates Ibsen as a rebel for leftist causes.

1892 — Sidney Webb, a founder and close associate of Shaw, is elected to the London City Council along with five other Fabian Society members. Widowers’ Houses, Shaw’s first “unpleasant” play, is performed on the London stage.

1893 — Shaw writes The Philanderer and Mrs. Warren’s Profession, his two other “unpleasant” plays. The latter is refused a license by the royal censor because its subject is prostitution; as a result, the play is not performed until 1902. Widowers’ Houses is published.

1894 — Seeking a wider audience, Shaw begins a series of “pleas ant” plays with Arms and the Man, produced this year, and Candida, a successful play about marriage greatly influenced by Ibsen’s A Doll’s House.

1895 — Shaw writes another “pleasant” play, The Man of Destiny, a one-act about Napoleon, and drama criticism for the Saturday Review.

1896 — Shaw completes the fourth “pleasant” play, You Never Can Tell. He meets Charlotte Payne-Townshend, a wealthy Irish heiress and fellow Fabian. The Nobel Prizes are established for physics, medicine, chemistry, peace, and literature.

1897 — Candida is produced. The Devil’s Disciple, a drama set during the American Revolution, is successfully staged in New York. Shaw is elected as councilor for the borough of St. Pancras, London; he will serve in this position until 1903.

1898 — Shaw writes Caesar and Cleopatra and publishes Mrs. Warren’s Profession and The Perfect Wagnerite. His first anthology of plays, Plays Pleasant and Unpleasant, is published. He falls ill and, believing his illness fatal, marries his friend and nurse Charlotte Payne-Townshend; his wife’s fortune makes Shaw wealthy.

1899 — You Never Can Tell premieres. Shaw writes Captain Brass bound’s Conversion.

1900 — The Fabian Society, the Independent Labour Party, and the Social Democratic Federation join forces to form the Labour Representation Party, which is politically allied to the trade union movement. The party wins two seats in the House of Commons. Captain Brasshound’s Conversion is produced. Three Plays for Puritans collects The Devil’s Disciple, Caesar and Cleopatra, and Captain Brassbound’s Conversion.

1901 — Strindberg’s Dance of Death is completed. The Social Revolutionary Party, instrumental in the Bolshevik Revolution, is formed in Russia. Shaw writes about the eternal obstacles in male-female relations in his epic Man and Superman, which he subtitles “A Comedy and a Philosophy.” He also publishes The Devil’s Disciple and sees Caesar and Cleopatra produced for the first time.

1902 — A private production of Mrs. Warren’s Profession is staged at the New Lyric Theatre in London.

1903 — Shaw publishes Man and Superman. The Admirable Bashville is produced.

1904 — John Bull’s Other Island premieres in London.

1905 — Shaw writes the play Major Barbara, through which he at tempts to communicate many of his moral and economic theories, including the need for a more fair distribution of wealth. It is produced this year, as is Man and Superman. In New York City, Mrs. Warren’s Profession is publicly staged for the first time. Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis is published posthumously. The Sinn Fein party, dedicated to Irish in dependence, is founded in Dublin.

1906 — The Labour Representation Party wins twenty-nine seats and shortens its name to the Labour Party. Henrik Ibsen dies. Shaw’s The Doctor’s Dilemma, a satire on the medical profession, is produced.

1909 — Shaw writes The Shewing-Up of Blanco Posnet and the one act farce Press Cuttings, both banned by the royal censor.

1910 — Shaw writes Misalliance, which he compares to Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew.

1912 — He publishes Misalliance, and his satire Androcles and the Lion is staged for the first time.

1913 — A German language version of Pygmalion, another satire Shaw wrote in 1912, premieres in Vienna.

1914 — With World War I imminent, Shaw publishes a polemical antiwar tract, Common Sense About the War, which provokes a popular backlash and public denouncement. Pygmalion is produced for the first time in English.

1917 — Dejected over the war, Shaw writes Heartbreak House.

1919 — Heartbreak House is published in New-York.

1920 — The canonization of Joan of Arc gives Shaw the idea for a new play. Heartbreak House is produced in New York.

1921 — Shaw publishes five linked plays begun during the war under the title Back to Methuselah, a dramatic work that begins in the Garden of Eden and ends in the year A.D. 31,920.

1923 — Shaw writes Saint Joan, which is produced and hailed as a masterpiece.

1924 — Saint Joan is published.

1925 — Shaw is awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature for Saint Joan. He donates the prize money to fund an English translation of the works of August Strindberg.

1928 — Shaw publishes his nonfiction The Intelligent Women’s Guide to Socialism and Capitalism and writes The Apple Cart, a dramatic comedy set in the future.

1929 — The Apple Cart is produced.

1931 — Shaw visits Russia, where he meets Josef Stalin and Maxim Gorky. He completes the play Too True to Be Good, which explores how war can undermine established morals.

1932 — Too True to Be Good is staged for the first time.

1933 — An international celebrity, Shaw makes his first trip to America. On the Rocks and Village Wooing are produced.

1934 — Shaw writes the plays The Simpleton of the Unexpected Isles, The Six of Calais, and the first draft of The Millionairess during a cruise to New Zealand. Simpleton is produced this year.

1938 — Geneva, a play that imagines a successful League of Nations, premieres.

1939 — Shaw writes Good King Charles’s Golden Days, which is produced this year. He wins an Academy Award for the screenplay for Pygmalion, over which he exercised tight control.

1943 — His wife, Charlotte, dies after a long illness.

1947 — Shaw completes the play The Buoyant Billions.

1948 — The Buoyant Billions is produced in Zurich.

1949 — Shaw’s puppet play, Shakes Versus Shav, is produced.

1950 — George Bernard Shaw dies on November 2 from complications related to a fall from a ladder. He bequeaths funds for a competition to create a new English alphabet based on phonetics rather than Roman letters. The competition, won in 1958 by Kingsley Read, results in the Shavian alphabet.

INTRODUCTION

In one of Katharine Hepburn’s early films, Morning Glory (from a 1933 play by Zoe Akins), Hepburn plays a self-confident, self-reliant, fearless, and outspoken young woman, ambitious to become a great actress in New York — in short, Hepburn plays herself. In the film, in an exchange with a producer (played by the ever-dapper Adolphe Menjou), Hepburn explains that she has done several major roles back home in her local Vermont theater company, including a role “in Shaw’s You Never Can Tell.” Menjou then asks, “Bernard Shaw?” and she replies, “The one and only.” They continue: “You think Shaw’s clever?” “He’s the greatest living dramatist.” “You really think so?” “I know it.” She goes on to explain that she once wrote to Shaw and received a reply (which she carries with her), and that she will always have a Shaw play in her repertoire “as long as I remain in the theater.” The version of herself Hepburn plays here amounts to a version of the headstrong Shavian heroine. In the real theater world, Hepburn played the title role in one of Shaw’s late but not-quite-great plays, The Millionairess, in a New York and London production (1952). Some twelve years earlier, when she was starring in the film The Philadelphia Story, Shaw himself had suggested that she was just the sort of actress to play his millionairess. But even apart from her actual stage experience with Shaw, Hepburn, like her parents before her, was a Shavian — that is, influenced by Shaw’s ideas; full of unorthodox views, especially about religion; independent-minded; strong-willed. That was the appeal of Shaw in the 1930s, when the number of his plays that were part of the active repertory of the world’s theater — say twenty plays — was greater than that of almost any other playwright, Shakespeare, as always, excepted. The modernists — Eliot, Joyce, Beckett — and modernism had not yet completely triumphed, so that Virginia Woolf and Leonard Woolf could argue about Shaw’s place in modernism, Virginia maintaining that Shaw was out of date, and Leonard asserting that if it had not been for Shaw’s work of educating the first generation of the twentieth century about everything, the modernists would have found no audience. So Shaw still could seem ahead of his time — enough ahead of his time for a most modern woman like Katharine Hepburn (and the character she played in Morning Glory) to admire him as a culture hero, an advanced thinker, and a modern playwright. The four plays in the present volume are test cases both for Shaw’s achievement in drama and for the destinies of his headstrong heroines. The plays also give more trouble than those in Barnes & Noble Classics’s other edition of Shaw — Mrs. Warren’s Profession, Candida, The Devil’s Disciple, and Man and Superman — more trouble in that they have more unresolved chords than his earlier plays, and so are more difficult to understand; they reflect a Shaw troubled by the role of the artist in the world and by the world’s role in the universe. Heartbreak House, the last play in this edition, was written during World War I; it expresses Shaw’s struggle not to be defeated by all the evidence that the Devil in Man and Superman, who argued that Man is primarily a destroyer with his heart in his weapons, was right after all. Just the number of the war dead — the prodigiousness of which can be gauged by considering that United States fatalities for the whole of the Vietnam war, some 54,000, about equaled the number killed on one side on a single day of battle on the Western Front. Major Barbara and its two predecessor plays — Afan and Superman (1903) and John Bull’s Other Island (1904; Shaw’s only major play about and set in his native Ireland) — form a trilogy on the theme of human destiny within a social order and a cosmic perspective, as Bernard Dukore has suggested in Shaw’s Theatre (see “For Further Reading”). All three plays use forceful images of heaven and hell, and debate propositions and ideas that would transform the world from a hellish place to a more heavenly one. But where Man and Superman projects an optimistic vision of human potential, both John Bull’s Other Island and Major Barbara end more ambiguously — that is, with the sense that any hope that humankind will put an end to war and waste remains in the realm of madness or fantasy — though Shaw still commits his characters to the fervent attempt to turn hope into reality. By the time Shaw wrote Heartbreak House, during World War I, he found himself a powerless witness to death and destruction on a massive scale such as the world had not seen. Heartbreak House records most precisely the reaction of the playwright to be like that of a man looking down from the top ledge of a skyscraper who becomes afraid, not that he will fall, but that he will jump. The tension in the play derives from Shaw’s instinct to resist yet give full expression to the allure of the jump that would let him be finally done with the world. John Bull’s Other Island made Shaw famous and popular in 1904. Previously he had been something of a coterie dramatist with a few mildly successful plays to his credit. But the topicality of John Bull’s Other Island — together with the fortuitous attendance at a performance by King Edward, during which he laughed frequently and noticeably, and apparently with such gusto that he broke his chair — raised Shaw’s recognition and reputation to a hitherto unattained level. Certainly Shaw’s Irish play has its hilarious moments and episodes; but it is also suffused with sadness over the spiritual paralysis Shaw diagnoses as deriving from his countrymen’s tormenting imagination, which drives them to flee from reality to the bottle and futile dreams. The play’s embodiment of this tragic condition is a defrocked priest, Father Keegan, who expresses in the last scene an ideal social and metaphysical order: In my dreams [Heaven] is a country where the State is the Church and the Church the people: three in one and one in three. It is a commonwealth in which work is play and play is life: three in one and one in three. It is a temple in which the priest is the worshipper and the worshipper the worshipped: three in one and one in three. It is a godhead in which all life is human and all humanity divine: three in one and one in three. It is, in short, the dream of a madman. Yeats in his old age cited this speech of Keegan along with a very few other passages in literature as moving him greatly; the line “How can we know the dancer from the dance?” from Yeats’s poem “Among School Children” seems to echo Keegan. At its core Keegan’s dream proposes that all life is holy because it is whole, that the material and the metaphysical are indivisible, that the social and the spiritual are equally in need of attention. And though that proposition is presented as and perhaps acknowledged to be a madman’s dream, it lies at the heart of the ideas that Shaw’s next big play, Major Barbara, confronts.

MAJOR BARBARA Major Barbara was successfully revived by the Roundabout Theatre in New York in 2001 The revival elicited the following encomium from Margo Jefferson, writing in The New York Times Book Review (August 5), after she has noted that “Shaw was a true artist, a master of multiple forms”: The language and the complexity of the world Shaw made still excite. It isn’t just the war of wills between Barbara Undershaft, the society girl who turns to the Salvation Army in her need to do good and save souls, and her father, whose munitions empire commits him to war and destruction. It is out-of-work cockneys, young men about town and rich dowagers, all living on habit, instinct and the calculation needed to bridge the gap between what they have and what they want. And, in all Shaw’s work, it is the rigorous musicality of his language. Jefferson is surely right that Shaw’s achievement in Major Barbara has two aspects: the variety and plenitude of the world he unfolds before us; and the designing and composing of sentences into harmony, counterpoint, and rhythmical ideas. But let me add a third aspect: the shaping and arranging of action. And it is not for naught that Shaw knew Shakespeare’s plays as he knew Beethoven’s nine symphonies note for note. But Shaw’s view of Shakespeare has often been misunderstood — Shaw loved Shakespeare’s art but did not love what he took to be Shakespeare’s stoic-pessimistic view of life. He said once that no one would ever write a better play than Othello, because humanly speaking, Shakespeare had done the thing as well as it could be done; in the same way no one could improve on Mozart’s music. Shaw learned much from Shakespeare — how much is especially evident in Major Barbara. One of Shakespeare’s triumphant strategies for getting a maximum of meaning out of dramatic form is to parallel actions and stage images in one dramatic scene with another, thereby causing the audience to compare the behavior of one character to that of another. Characters and actions become metaphors — that is, we come to understand a character or an action better, or to rethink our attitude toward it, by its being set parallel to another character in an analogous situation, or by the placement of a similar action in a different context. For example, Major Barbara enacts a drama of loss of self and rebirth in terms of finding one’s home and one’s work. The protagonist of the play, Barbara Undershaft, is the daughter of an aristocratic mother, Lady Britomart, and a fabulously wealthy and powerful munitions maker, Andrew Undershaft, who is also a foundling (the play has a strong fairy tale/parable quality). In the first act, Andrew Undershaft returns home, to a great house in fashionable Wilton Crescent, after a long absence from family life; he proves so fascinating to his grown children, especially Barbara, that by the end of the act, his wife has been reduced to tears because all her children have deserted her to follow their father into another room, where Andrew has agreed to participate in a nondenominational religious concert. Finally, though, even Lady Britomart is lured by the music and joins her husband and children. The second act is in every way patterned after the action of the first, though in appearance they could not be more different. Barbara has invited her father the next day to watch her work at her Salvation Army shelter in a neighborhood that is the exact opposite of Wilton Crescent. There, her millionaire father finds cold, brutality, hunger, hypocrisy, and the work of conversion, where Wilton Crescent seemed to provide warmth, comfort, formality, and conversation. But Shaw’s aim is to show that both places are alike in being devoid of authentic religious feeling and genuine spiritual nourishment. Shaw does so by having Undershaft do wittingly to Barbara in the second act what he does unwittingly to her mother in the first act: undermine her sense of self and position. In Lady Britomart, the undermining is limited and temporary, but in Barbara’s case it induces in her a dark night of the soul that makes her resign her job with the Salvation Army. For her father shows his spiritually vital daughter, whose greatest hunger is to affect and transform the souls of people, that her organization can be bought. When the Salvation Army general, Mrs. Baines, arrives and announces that a number of shelters will close unless the Army secures substantial donations from wealthy benefactors, Under - shaft offers to make a £5,000 contribution, which in turn will compel equal contributions from, among others, a whisky distiller. The general cheerfully accepts, but Barbara is horrified to see the Army “sell itself” by taking donations from a whisky distiller and a munitions maker. Her principled posture makes her resign in a state of tearful despair. (For those who believe with Oscar Wilde that life imitates art and not the other way around, I note that, according to the Associated Press on January 3, 2003, the Salvation Army refused a donation of $100,000 from a lotto winner in Naples, Florida, on the grounds that the Salvation Army counsels families who have lost their homes due to gambling, and would therefore be hypocritical in accepting such a donation!) When the shelters are saved the Army members gather together behind a band that includes both Barbara’s father and her fiance, and march off for a great celebration at the Assembly Hall, leaving the deserted Barbara, stripped of her identity as a saver of souls and stripped of her real home, which was the shelter. Both the first and second acts, therefore, end with a woman in tears and feeling that everything she valued has been taken from her, put in that state by Andrew Undershaft, her misery accompanied by the sound of music from another place. And just as Shakespeare in Henry IV, Part One describes Hotspur calling for his horse after he has plotted to rebel against the king, and then Falstaff in the next scene calling for his horse during the Gadshill robbery, in order to make us think about what Hotspur’s rebellion has in common with Falstaff’s robbery, in Major Barbara Shaw parallels Lady Britomart and Barbara in order to make us see more complexly the nature of Barbara’s loss. Since Barbara has now lost the two things that above all give us our sense of ourselves — work and home — she will spend the third act trying to find new versions of both, which together mean a new self. But you need not take my word that setting up parallel actions is Shaw’s method, for he says so himself in the preface, when he explains how he has shown us two attempts on the part of transgressors to pay off the Salvation Army: Bill Walker for having struck Jenny Hill, and Horace Bodger for selling whisky to the poor: But I, the dramatist, whose business it is to shew the connexion between things that seem apart and unrelated in the haphazard order of events in real life, have contrived to make it [that the Army will take Bodger’s atonement money but not Bill‘s] known to Bill, with the result that the Salvation Army loses its hold of him at once (p. 35). Here we see Shaw doing just what Aristotle in his Poetics says is the mark of genius in the poet (because it cannot be learned): intuiting the hidden similarity between two apparent dissimilars, or making metaphors. Shaw makes Bill Walker see the comparison so that we will see it, just as Shakespeare makes Prince Hal see the connection between the apparent opposites Falstaff the coward and Hotspur the daredevil, which is that both live outside of all order. The friends to whom Shaw read Major Barbara were strongly moved by the power of the second act, in which Andrew Undershaft demonstrates the power of the pound over religion, and in doing so makes his daughter feel as if she has lost all purpose in life. In one of the play’s most profound aphorisms, Undershaft reproves Barbara for feeling self-pity by observing to her: “You have learnt something. That always feels at first as if you had lost something” (p. 132). Perceiving something new often means abandoning a cherished view or opinion, and it often hurts to do so, but Shaw puts the emphasis on “at first.” In other words, one can find compensations for losses; one can mend a broken heart. And so Barbara does when she gets to her father’s cannon-works town with its powerful foundry, its well-tended workers’ dwellings, its families, and its children. She sees that here is a real challenge for her: Can she induce well-fed and well-paid workers to pay attention to their spiritual selves, to their salvation? She decides to renew hope and marry the man who will take over the cannon works from her father. That man turns out to be Cusins. From the premiere of the play in 1906 people have found its ending ambiguous: Do Barbara and Cusins succumb to the allure of materialism in agreeing to take over the cannon works from Undershaft? Or do they intend to use their new power to “make war on war”? Shaw leaves the question unresolved, though he clearly leans toward the latter possibility. In any case, as he said in the postscript to the preface to Back to Methuselah (1921), which he wrote in 1944 for the Oxford World’s Classics edition: It is the job of classic works to “try to solve, or at least to formulate, the riddles of creation.” Cusins formulates one of the riddles of creation in an exchange with Barbara over how the cannon works are to be used. Cusins says he will use them to give power to the people. But Barbara laments the power to destroy and kill. Cusins replies: “You cannot have power for good without having power for evil too” (p. 155). Another way of formulating that idea is: Undershaft’s weapons and explosives are as good or as bad as the man making them (to adapt a line from the film Shane). Barbara sees the cannon works as her opportunity to raise “hell to heaven.” Her most immediate impulse, however, is to escape to heaven, away from the “naughty, mischievous children of men.” But her courage returns, and she unites herself to both Cusins and her father (while she also reaffirms her bond with her mother, an affirmation that is the seal of her reborn self). Jonathan Wisenthal (in The Marriage of Contraries) has argued persuasively that the end of the play anticipates a tripartite union of three kinds of power: material (Undershaft), intellectual (Cusins), and spiritual (Barbara). But Shaw is well aware that such a union, like Father Keegan’s vision of three in one, is not realized in the play, and may be only a madman’s dream.

Date: 2015-04-20; view: 841

|