CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

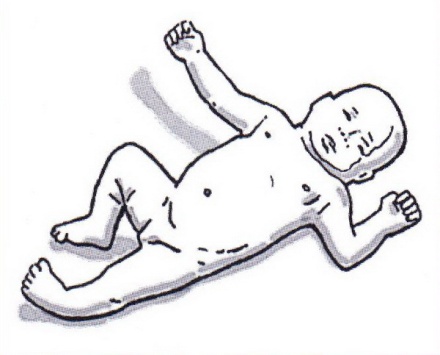

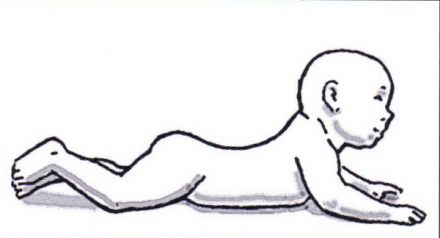

The Search For Wellness.When we began treating brain-injured children, most of our children were unable to walk or to talk. Many lacked both of these abilities. Our first focus, therefore, was on understanding the development of walking and talking. Our study began as most studies do, with a search through the medical literature to learn what had been recorded up to that time on e subject. We were astonished. We were dumbfounded to discover at virtually nothing had been written about the development of young child. Arnold Gesell, a pioneer in the study of child development, was all there was. It appeared that Gesell was perhaps the first man in all of recorded medicine to make his life's work the if the healthy child. Gesell had certainly studied the well child on a broad scale, not only a child's movement and speech but his social growth as well. He had not, however, attempted to explain the child's growth; he had devoted himself to being a careful observer of the child and how he grew. We had a much broader interest. Where Gesell recorded when the child learned to move and speak, we wanted to know how he did it, and why he did it. We wanted to identify those factors significant to the child's growth. Clearly we had to seek these answers on our own. At first we went to those people who might be expected to know. "How does a child grow?" we asked the experts. "What are the factors necessary to his growth?" We asked pediatricians, therapists, nurses, obstetricians, and all the other specialists that were concerned with the growth of the well child. We were surprised and distressed by the lack of knowledge we encountered. Gradually we came to understand the reason: the people we consulted seldom saw a well child! The reason for taking a child to the doctor, nurse, or therapist, obviously, is that the child is not well. So the people we were asking saw primarily sick children. We found, therefore, both in the literature and in our interviews with other professionals, that though much information existed about the unwell child, very little existed about the well child and why he grows as he does. Finally we realized that those who knew most about the growth of healthy children were mothers. But though mothers had a great deal to tell us they were naturally a bit vague as to the exact times that a child did what he did, and what was significant in what he did. For a scientific inquiry we needed more precision, and so we decided to go to the source—the infants themselves. The world became our laboratory and babies our most precious clinical material. We asked permission to study every baby we could find. We focused first on walking. We followed the child carefully from the moment he was born until he learned to walk. What, we asked ourselves, were the things that would prevent walking if they were denied to a child or removed from his environment? What were the things that, if given to the child in abundance, would speed his walking? We studied many, many newborn well children. After several fascinating years of study, we knew we had discovered the pathway that each of us had individually trod as babies. We also came to feel that we understood this pathway In a dark and formerly unpromising tunnel, we were beginning to see the light. It was particularly evident that this road of growth that the baby followed to become a human being in the full sense of the term was both a very ancient road and a very well-defined one. This road, it was interesting to note, permitted not the slightest variance. There were no detours, no crossroads, no intersections, nothing that changed along the way. It was an unvarying road, which every well child followed in the process of growing up. Anyone who could observe carefully could learn how a well baby learned to walk. When all extraneous factors not vital to walking were removed, it became clear that along the road to walking there were four vitally important stages. The first stage began at birth, when the baby was able to move his limbs and body but was not able to use these motions to move his body from place to place. This we called "movement without mobility (see Figure 2.1).

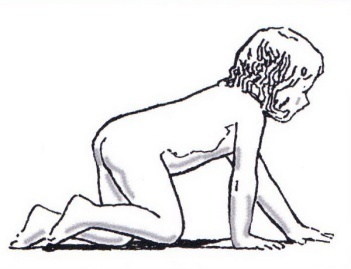

The second stage occurred when the baby learned, sometimes within hours, that by moving his arms and legs in a certain manner with his stomach pressed to the floor, he could move from Point A to Point B. This we called "crawling" (see Figure 2.2). Quite a bit later, stage three occurred, when the baby learned to defy gravity for the first time and to get up on his hands and knees land move across the floor in this more effective and more skillful manner. This we called "creeping" (see Figure 2.3). The last significant stage occurred when the baby learned to stand up on his feet and walk, the stage we all know as "walking" (see Figure 2.4). It is vital to understand the significance of these four stages. We can see their importance if we view them as schools. Think of stage one, that of moving arms and legs and body without mobility, as kindergarten; think of stage two, crawling, as grammar school; think of stage three, creeping, as high school; and then think of stage four, that of walking, as college. No child ever misses an entire school. No child completes college before he completes high school. There is an ancient saying that you have to creep before you can walk. We now feel safe in saying that you have to move your arms and legs before you can crawl, and you have to crawl on your belly before you can creep on hands and knees. We became convinced that no well child ever missed a stage along this road, and we became convinced of this despite the fact that mothers sometimes reported that their children did not crawl. However, when such a mother was asked, "Do you mean that your child simply lay in his crib until the day he started to creep on hands and knees or stand up and walk?" Mother generally reconsidered and allowed as how the child had crawled for a short period of time. While there was no way to travel this road without passing each and every milepost, there was indeed a difference in the time factors. Some children would spend ten months in the crawling stage and two months in the creeping stage, while other children spent two months in the crawling stage and ten months in the creeping stage. However, these four significant stages always occurred in the same sequence. Along the ancient road there were no detours for the well child. So convinced did we become of this that we also became convinced of two other factors. First, we became convinced that if an otherwise well child were to miss, for any reason, any stage along this road, that child would not be normal and would not learn to walk until given the opportunity to complete the missed stage. We were persuaded, and we still are, that if one took a well child and suspended him by some sort of sling device in midair when he was born and fed him and cared for him until he was twelve months of age and then placed this child on the floor and said, "Walk, because you're twelve months of age and this is the stage at which well children walk," that the child would, in fact, not walk. He would instead first move arms, legs, and body; second, crawl; third, creep; and fourth and last, walk. This was not a mere chronology of events but instead was a planned road in which each step was necessary to the subsequent step. Second, we became convinced that if any of these basic stages were merely slighted, rather than wholly skipped, as for example in case of the child who had begun to walk before he had crept enough, there would be adverse consequences such as poor coordination, poor concentration, hyperactivity, difficulty in becoming totally right-handed or left-handed, and learning problems—particularly in the areas of reading and writing. Crawling and creeping, it began to appear, were essential stages not only in learning to walk but also in the overall programming of the brain, stages in which the two hemispheres of the brain learned nr to work together. After years of observing thousands of children in many parts of the world, we are more convinced than ever that when we see a child did not go through each of these major stages in order, we are looking at a child who later on will show evidence of having a neurological problem. Now we had our first set of facts. We knew what was normal, at least so far as mobility went. This helped to define the next two task: 1) To learn how this knowledge could be used to benefit a brain-injured child, and 2) To learn what was normal in all the other areas of function that are important to human beings. After two decades of work it became clear that what we were studying was not just therapy, or mobility, but child brain development. To this day we have not exhausted the thousands of ways to stimulate the brain and enrich the environment. As a result, more brain-injured children are seeing, hearing, walking, and talking than have ever done so before. In some cases, they have become totally well. 3. A New Kind Of Kids. The search for better and better ways to improve the mobility of our brain-injured children led us naturally to examine their overall intellectual development, and in the early 1960s we began to teach very young brain-injured children how to read. Many of our children had problems in understanding, and we reasoned that the earlier they got started learning to read the better would be their chance of success. We were also treating many children who had no problems whatever with understanding. They were injured in the midbrain and subcortical areas of the brain. They had huge problems in mobility, language, and manual competence, but they understood very well. In fact, these children, who are frequently hurt in utero, are extraordinarily intelligent. While their well brothers and sisters and next-door neighbors are crawling and creeping and walking and jumping all over the house, they are forced, by their injury, to watch and listen. They quickly develop very sharp powers of observation and comprehension. As a result they are highly tuned in to everything and everyone around them. Since they move poorly or not at all, they have a great need to charm adults into getting them whatever they need or want. The result is that by the time these children are two or three years old they have the understanding of children several years older, and they will maintain this intellectual edge throughout life. We saw our challenge as learning how to fix these children so that they could walk and talk and use their hands like all children do. Since they had very high understanding, we reasoned that they also could benefit from an early reading program. So we began to teach parents how to teach their severely brain-injured two- and three-year-olds to read. The results were immediate and astounding. The children injured in the midbrain and early subcortical areas who did not have understanding problems also learned to read with astonishing ease. Even more astounding, children with understanding problems also learned to read quickly and easily. Still more important, we were surprised to see that their comprehension improved substantially as a result of this new stimulation. The children were thrilled with this new program, their parents were elated, and, of course, so were we. We did not realize at the time that we were entering a whole new field of knowledge in which we would gain understanding of the process of intellectual growth and vital new insights into the development of the well baby. By this point, brain-injured children were coming regularly to The Institutes to be evaluated by the staff. New programs were designed for each child based on the progress he or she had achieved, and parents would return home to do their new program on a daily basis for approximately six months. Their home program had been a balance between a mobility program and a physiological program to insure good health and function. Now we added an intellectual program of early reading. As a result of this program, we began to see children who— although they were still severely brain-injured—were able to read and comprehend whatever they read years before well children of the same age. These four-year-olds were not yet able to walk or talk, but they could read at a third- or fourth-grade level, and occasionally higher. What did it mean? Was it possible to be severely brain-injured from the waist down and intellectually superior from the waist up? Was it an advantage to be severely brain-injured? Nobody thought that. What did it mean? We began, reluctantly at first, to ask ourselves what was wrong—not with the brain-injured child on the road to recovery, but with his healthy peers who could not do things that this severely brain-injured child could do. It seemed clear that well kids were not as well as they ought to be. At just about the time when this uncomfortable thought was haunting us, we began to see a new kind of kid. We should have predicted that he would start arriving on our doorstep, but we did not. Instead, he took us totally by surprise. He came into our offices with his mother and father and his brain-injured brother or sister. He usually sat in on all the adult talk, the long history, the evaluation, and the lengthy programming sessions. He frequently asked very incisive questions and often volunteered answers to the questions that came up. He was articulate, extremely well-coordinated, very well-behaved, and totally and completely involved with the treatment program of his hurt brother or sister. However, this child was not the older brother or sister of the brain-injured child. This was the younger brother or sister of the brain-injured child. This was the baby of the family. He was not like any other child we had ever met. He was a bit like a dehydrated adult, only more charming and likeable than most adults tend to be. All the characteristics for which children are loved he had in abundance. All the characteristics for which children are sometimes considered a pain in the neck were absent in him. We should have expected him, but we did not. When his brain-injured older brother or sister began on a daily neurological program he had been a newborn baby. Mother had very wisely made sure that he was with her and his hurt brother or sister at all times. The baby was always included in whatever mother and hurt child were doing on their neurological program. If older brother was crawling on his belly, then that was a good opportunity for baby to crawl with him. And so the baby had the maximum opportunity to be on his belly on the floor to explore and to crawl. If older brother was doing log rolls to improve his balance and vestibular development, then baby got to do the same log rolls side by side with big brother. And so the baby's brain had more stimulation to the balance and vestibular areas than it would have otherwise received on a hit-or-miss basis. When mother started to teach older brother how to read, the baby sat by his side. Every word that older brother saw, baby saw. Because older brother had visual problems, the reading words were written very large. The baby could see these large words easily, and as a result his visual pathways were given the opportunity to develop faster and better. These words were chosen from the household environment, so the baby could easily understand them as well. By the time the baby was less than a year old, he could actually differentiate many single reading words from each other. In short, mother and father had taken great pains to provide their brain-injured child with an excellent neurological environment so that they could grow those pathways that had been injured and close the break in the circuit created by the brain injury. The environment was rich in that it provided abundant sensory stimulation to the pathways that go into the brain and ample motor opportunity to use the pathways that go out of the brain. We had theorized that if such an environment provided brain-injured children with the stimulation that they needed to become well, would it not also be beneficial for a well baby? After all, the well newborn baby must face the same challenges that confront the brain-injured child. Like the brain-injured child, the newborn is neurologically immature. In truth, the well newborn and the brain-injured child, although very different in some ways, are neurologically very similar indeed. If we now knew how to get blind brain-injured children to see, deaf brain-injured children to hear, and paralyzed brain-injured children to move, did we not also have the answers to create a superb environment for the newborn baby? A well-designed program would provide the newborn with an environment that encourages his development on purpose. In addition, it would act as a kind of insurance plan by handling any neurological problems he might have if we left his growth and development to chance. This was a wonderfully exciting prospect for the staff. It made for many debates and discussions at three o'clock in the morning. These usually ended when someone observed that we had an army of hurt kids who were depending on us to find the answers that would help them to get well. Our team was dedicated but it was small. We knew we could not afford to think about making well kids better while hurt kids still struggled to survive in a world in which they were regularly warehoused and forgotten. And so our dream of newborn babies having the benefit of this precious knowledge remained only a dream for a while. In time, however those highly articulate, very well-coordinated, and absolutely charming tiny children started appearing in our offices with predictable regularity. They were not a dream. They were no longer a theory. They were very real and very, very impressive. Now we had no choice. These children had real names and real faces. We were hooked. We knew that no matter how long it took no matter how little funds there were to go around, we were going to have to do something about well kids. 4. About The Brain. The human brain is an superb beyond imagination. Oddly enough, it is commonly believed that there is little known about this mysterious organ except that it weighs three to four pounds and is responsible for virtually everything that we do. In truth, the brain is not a mysterious organ at all. A great deal has been known and understood about the brain for thousands of years. Of all the organs of the body it is the most capable of change. In fact, it is constantly changing, in a physical and functional way, either for better or for worse. It is very important to remember that when we speak of the human brain we are speaking of that physical organ that occupies the skull and the spinal column and weighs three to four pounds. We are not speaking of that nebulous thing called "the mind." The confusion between the organ called "the brain" and the idea called "the mind" has created problems in the past. The mind has defied any agreed upon definition of what it is or what it is not. The brain, however, is material. It is easier to study. We can see it, feel it, and smell it. We can even taste it if we are inclined to do so. The brain is a nice, clean orderly organ whose job is to take in data and process that data in such a way that its owner can relate to his environment appropriately at all times. This is a tall order, and the brain handles it on a twenty-four-hour-a-day basis for the entire life of the individual. The brain continues to grow from conception throughout life, but the pattern of that growth is not even. The brain grows explosively from conception to six years of age. After that growth continues, but compared to that initial period, growth after age six is slight by comparison. The growth of the head reveals this clearly. From conception to birth the head grows from zero to thirty-five centimeters in circumference. From birth to age two-and-a-half years, it grows another fifteen centimeters. From the age of two-and-a-half years to adulthood, the head will only grow another five centimeters, and most of that will take place before six years of age. From the moment of birth, the rate of growth of the brain is on a descending curve. Each day the brain grows a little less than it did the day before. During the period of greatest growth, the baby is able to take in raw information at a rate that is truly astounding. But this process will be a little bit slower each day. Some people are interested in providing stimulation to the baby in utero, but this has not been our area of search and discovery. While there may be much to learn about the baby in utero, we will confine ourselves to the time following birth, when we are able to observe and evaluate the baby and see what he needs and how he reacts to the things we are doing with him. Since the critical period of brain growth is between birth and six years, it is clear that the earlier we provide baby with stimulation and opportunity, the more he will be able to take in the stimulation and use the opportunity to its fullest. Sadly, the world has tended to look at brain growth and development as if it were predestined and unchangeable. The truth is that brain growth and development is a dynamic and ever-changing process. It is a process that can be stopped, as it is by profound brain injury. It is a process that can be slowed, as it is by an environment that inhibits the opportunity of the child to explore and discover his environment through seeing, hearing, feeling, tasting, and smelling, and through inhibiting the opportunity to move, speak, and use his hands. But most important, it is a process that can be accelerated and enhanced. All that we need to do to speed development is to provide visual, auditory, and tactile stimulation—with increased frequency, intensity and duration—in recognition of the orderly way in which the brain grows. And how does the brain grow? The brain grows by use. There are very few sentences composed of only five words that contain more power to change the world than this one: The brain grows by use. Just like the biceps, the brain grows by use. Those who use their biceps very little have small, undeveloped, weak biceps. Those who use their biceps an average amount have average biceps. Those who use their biceps an extraordinary amount have extraordinary biceps. There is no other possibility. The same is true of the brain, because the brain grows by use. It was our hurt children who proved this to us. When we began to treat our brain-injured children successfully, they began to develop normal function. Children who had been unable to move began to move. Children who could not walk began to walk. Children who had poor understanding began to understand the world around them. A characteristic of brain-injured children is that they are physically small. They have very poor physical structures compared to their healthy peers. The majority of the children that we see are below the tenth percentile in their physical measurements. They have very small chests. They often have small heads, and their overall stature is much less than their healthy brothers and sisters. They are not small because they have inferior genes; they are small because their brain injury has prevented them from having normal function. That lack of function is responsible for their poor structure. There is an old law of nature that says that function determines structure. The brain-injured child demonstrates that the opposite is also true. A lack of function creates a lack of structure. We believed that if we could successfully treat the brain, the child would begin to increase his function, and that as this happened his structure would begin to change. This is exactly and precisely what happened. As children began to see for the first time and understand for the first time and move for the first time and walk for the first time, their structures started to change. They began to grow like weeds. Children whose height had been ten centimeters below their well peers began to grow at twice the rate at which a well child of the same age was growing. Children who had tiny chests and had suffered from chronic upper respiratory problems experienced chest growth that in some cases was three to five times faster than their well peers, and they stopped having upper respiratory infections. We were delighted but not surprised. This physical growth and development made total sense. The ability of Mother Nature to make up for lost time has a name—it is called the "Catch-up Phenomenon." What did surprise us, however, was a physical change that we were not expecting. Many of the brain-injured children we were treating were older than six years of age. In fact, some were not children at all, but adults. Although we did meticulous head measurements on all of the brain-injured children and adults who came to us, we really did not expect to see much growth in the circumference of the heads of children who were over six years of age. After all, we knew, as everyone knows, that brain growth is essentially over at six, and so the size of the head changes very little after this point. We were wrong. When we started to look at the changes in head growth of our brain-injured children who were well over six years of age, we were astounded by what we found. Although the head growth of their well peers was very slight, our brain-injured children's heads were growing two, or three, or sometimes even four times faster than their well peers. There was clear physical evidence that the brain grows by use. We have been watching this phenomenon for fifty years. The physical structures of brain-injured children who are not getting effective neurological treatment become worse with each passing day. But brain-injured children who are given the correct stimulation and the opportunity to function develop bigger and better chests, arms, legs, and brains. Likewise, well babies who are raised in an environment that is rich in stimulation, and where they have increased opportunity to function, also develop bigger and better chests, arms, legs, and— most important of all—brains. 5. The Newborn Baby. We adults have always assumed that being a newborn baby is a rather happy, halcyon state. A baby’s primary jobs seem to be eating and sleeping, and since we do not regard either as very difficult, we regard the newborn as enjoying a kind of baby honeymoon in which he has all the time in the world to get settled and comfortable in his new home. In fact, the newborn baby lives in no such world. He arrives having just completed what is arguably the most dangerous journey he will ever make. Even if he has had an easy delivery, he has still had a lot of work to do. We make much of the labor of mother in delivering a baby, as well we should, since it is physically hard work. But delivery is a partnership and the younger member of the team works as hard as the older member, if not harder, to get himself delivered. Once he has arrived he must adjust with amazing rapidity to the fact that he is no longer in an aqueous environment. He must not only learn to move his arms and legs without the support of this aqueous environment, but he must also quickly master the rudiments of breathing if he is to survive. It is astonishing that he does both of these things within seconds of being delivered. Once things have settled down and he has been given the once over by doctors, nurses, mother, and father, he must get down to the formidable task of figuring out what's what. At birth he cannot see. He is functionally blind. However, since he is exposed to light for the first time at birth he will immediately begin to try to use his vision. He will respond to light even though at first he can do so only briefly. His attempts to see will be short-lived. He will quickly grow tired and fall asleep after making an effort to see. He also cannot hear very much. It has been demonstrated that babies in utero respond to certain sounds and voices if they are loud enough. However, at birth the baby is, in a functional sense, deaf. He can hear some loud sounds but most sounds he cannot hear at all. Often the baby is born into an environment full of loud sounds. This creates auditory chaos for the baby This blurred sound will be hard for him to hear. The baby has tactile sensation, of course, but it is a very crude sensation. He can use his sense of smell to locate mother, and if he is in good shape neurologically he will be able to suck and swallow shortly after birth. He can move his arms and legs freely but forward motion is difficult at best, especially since he is usually bundled up like a mummy and placed on his back in the nursery. He can cry but his respiration is not yet good enough for him to be able to differentiate the sound that he makes. So he has one cry that he will have to use to communicate everything. He can grasp a finger placed into his hand at birth. Parents are often impressed with the strength of their newborn baby's grasp. However, while he can grasp very well and appears to be quite strong, he doesn't have the ability to let go even if he wants to do so. Overall the newborn baby exists in a blind, deaf, relatively insensate world in which he cannot move or use his hands, and has difficultly making sounds. This is not a happy state in which to be. Newborn babies are not the happy little bundles that we like to imagine they are. Instead they are very intent human beings struggling against very difficult circumstances to overcome blindness, deafness, and immobility. They are deadly serious and they should be. It is not easy or safe to be a newborn baby. The baby thinks it is his job to learn to see, hear, feel, and move at the earliest possible moment. He will use every waking moment to do this. The only real question is whether we will help him to get his job done or get in his way. No sane parent ever set out to get in the way of her newborn baby, but unwittingly we do it all the time. Some of our modern methods of delivery and early child care have developed with little rhyme or reason as to what we do or why we do it. When there is a reason for what we do, it is often simply our own convenience. Tragically, what may appear to be convenient or efficient in the adult world is often very bad for the tiny baby. Let's take a look at the typical environment of the newborn baby and ask this question: Is it set up for his benefit or ours? After being delivered he is usually taken away from his mother, wrapped up, and put on his back, and often placed, if mother permits, in a nursery with many other babies. Is this good for him or is it simply more convenient for the hospital staff to keep an eye on him? Nature has arranged a one mother/one baby ratio so that the newborn baby has mother watching and observing him at all times. We frustrate nature's design and take baby away so that he is one of a litter of babies that are watched over, not by their own mothers, but by a few conscientious nurses. To help the nurses keep an eye on so many babies at once, they are placed on their backs so that the nurses can be sure that they are breathing. The babies are covered in blankets because the nursery is not warm enough for them to be naked. If we made the nursery warm enough for the babies to be naked, then it would be too hot for the nurses. Although the babies cannot see or hear their mothers very well at birth, they can smell their mothers. When they arrive at the nursery they cannot smell mother any more. This is very upsetting for the baby. His survival imperative tells him, "Keep mother by your side at all times!" Therefore he will cry to call mother to his side. Since mother is a hundred yards away down the hall, she cannot hear his call and does not respond to it. Thus the baby knows his mother is not there and his attempts to call her go unanswered. This is not a comforting condition for the newborn. This frightening situation is compounded by the fact that he can hear the loud and repeated cries from the other babies in the nursery who are also trying to call their mothers. And we call this a "nursery"? Our intentions may be good but we have set up the environment to suit adult convenience. This environment could hardly be worse for the baby if we had set out intentionally to confuse, frighten, and frustrate him. When the baby arrives home he will continue to be bundled up no matter what time of year it is. We cool or heat our homes based on what is comfortable for us. But the baby needs a warmer environment than suits us, so he must be bundled up in the first few months of life. Wrapped up in blankets and dressed in clothing that fits like a snowsuit, he has a hard time moving at all. He already has a very chubby body that is hard enough to move, but dressed in thick diaper, a long-sleeved and long-legged baby suit, and then wrapped up in blankets, he would have to be a sumo wrestler to escape from the padding that envelops him. And he is desperate to move. He will move his arms and legs frantically at those rare times when he is freed from the confinement of his clothes and blankets. This is why diapering can be such a trial. It is usually the only time in the day when, for a fleeting instant, he is free. He struggles like mad, which usually drives us crazy since we are trying to put a diaper on him. It is not just the clothing and the blankets that frustrate his attempts to move. He is almost invariably placed on his back right from birth. In this position he is like a turtle turned upside down. All of the wonderful propulsive movements of his arms and legs are useless in this position. They produce no forward motion for him. However, when he is placed right-side up on his belly on a smooth, warm surface, all those seemingly random motions of his arms and legs become productive motions that produce forward movement. Whenever he is placed on his belly he will begin to make the thousand and one experiments that he must make to discover how to use his arms and legs to crawl. Nature has provided him with a rage to move his body, and he needs all the time he can get in order to do so. If you calculate how much time the modern baby is free to move unencumbered on his belly on a smooth, warm surface, you find it is almost zero. Even when we give him some opportunity to move, we restrict his playing field severely by placing him in a crib, playpen, swing, stroller, or "walker." Each of these devices was invented to act as a kind of remote babysitter. They are designed to restrict the baby so that we can go about our affairs without having to watch the baby so closely. This may seem like a necessary convenience or even a safeguard for the baby, but, in fact, it is neither convenient in the long run nor safe in the short run. There is nothing convenient about arranging the environment so that the baby cannot, try as he may, develop the vital abilities to crawl and creep freely. We know now that these are not just incidental stages in his development; crawling and creeping are critical to all aspects of neurological development. What may seem convenient today will turn out very inconvenient if his lack of creeping and crawling as a baby leads to difficulties later in life. As for safety, with a tiny baby there is no substitute for real vigilance. Every device that allows us to put distance between ourselves and the baby is a device that lulls us into a false sense of security. We have a clinic full of brain-injured children who were well children who climbed out of their cribs and fell on their heads or climbed out of their playpen and fell into the swimming pool. The lesson is simple—the closer the baby is to mother and the floor, the safer he will be in both the short run and the long run. As parents and as a society, we need to take a careful look at what our priorities are when we decide to bring a baby into this world. When we take a closer look, we may see that we have been selfish, insensitive, and extremely short-sighted to design the baby's environment almost totally for our comfort and convenience, thus denying the baby his birthright to move and explore and develop his abilities to their fullest. Although we have not meant to do so, we have gotten in the way of our babies' development. The needs of the newborn are much more important than our own temporary convenience. The environment should be designed to ensure his safety and long-term growth and development. The family and society as a whole stand to benefit hugely from the increased ability and happiness of babies who are raised in a way that meets their neurological needs. 6. Making The Alarm Clock Go Off. We have said much about what we should not do but we have only hinted at what we should do to create a better environment for our babies. Now let's take a closer look. It has long been believed that the key milestones in a child's development are achieved automatically, purely as a result of the child's growing older over time. This theory dictates that the child walks at age one due to some kind of built-in mechanism—rather like an alarm clock set to ring at twelve months that triggers the ability to walk. Simultaneously the alarm clock for talking rings, and he begins to say words. The same theory postulates a preset alarm clock for each and every significant stage of development. This theory suggests that the mere passage of time leads to the development of human ability and that the acquisition of ability is as inevitable as the sunrise and the sunset. This is called "readiness." For example, the alarm clock rings at six years of age and the child supposedly has "reading readiness." The concept of "readiness" and the whole alarm clock theory are patent nonsense. If reading readiness takes place at six years of age as the conventional thinking says it does, then how can we explain that thirty percent of the children in our school system will fail to learn to read properly by the age of eighteen? Why did their alarm clocks fail to ring at age six or seven? Why has it still not gone off by the time they are eighteen? It is even harder to explain the thousands of brain-injured children who have learned to read splendidly by the age of three. They were more than ready. They think reading is the greatest invention since mothers. Why did their reading "alarm clocks" ring early? It is true that at twelve months of age the average child will walk. But is this a cause-and-effect relationship? Is it the passage of time that has brought about this new ability? Obviously not. After living night and day with well children who were given a superb environment in which to develop from birth, we had to ask ourselves, "Why do they walk and talk and use their hands earlier than their peers?" Why do their alarm clocks go off before they are supposed to do so? Why are they learning earlier? One of the most exciting discoveries we were to make was that the process of growth and development is a product of the amount of stimulation in the child's environment. It is not determined by a preset alarm clock. We therefore began to look for every way we could to "set off the alarm clocks" for our brain-injured children, and we have found hundreds. We discarded the model of the preset alarm clock. What we had discovered was a simple and elegant truth: The brain grows by use, not a preset alarm clock. Brain growth can be speeded by increased stimulation at any point in life, but most especially at those times when it is growing fastest: in the first six years of life. The first six years of life are precious because during this time the brain grows at a tremendous rate. Brain growth is most dramatic in the first year. The development of the newborn's visual pathway offers clear proof of the dramatic growth of the brain in the first year of life. As we have pointed out, a well newborn is, like other little creatures, functionally blind in a practical sense. He can see only light and dark. He has a "light reflex." This means that if we shine a light into his eyes, the pupil will constrict to prevent too much light from entering the visual pathway. If we turn off the light, the pupil will again dilate to allow an acceptable amount of light to enter his visual pathway. Now consider three children: 1. A baby born two months premature in Chicago, who is now exactly two months old. 2. A healthy, full-term newborn conceived on the same day as the premature baby, also born in Chicago. 3. A healthy, three-month-old baby of a Xingu tribe in Brazil's Mato Grosso.

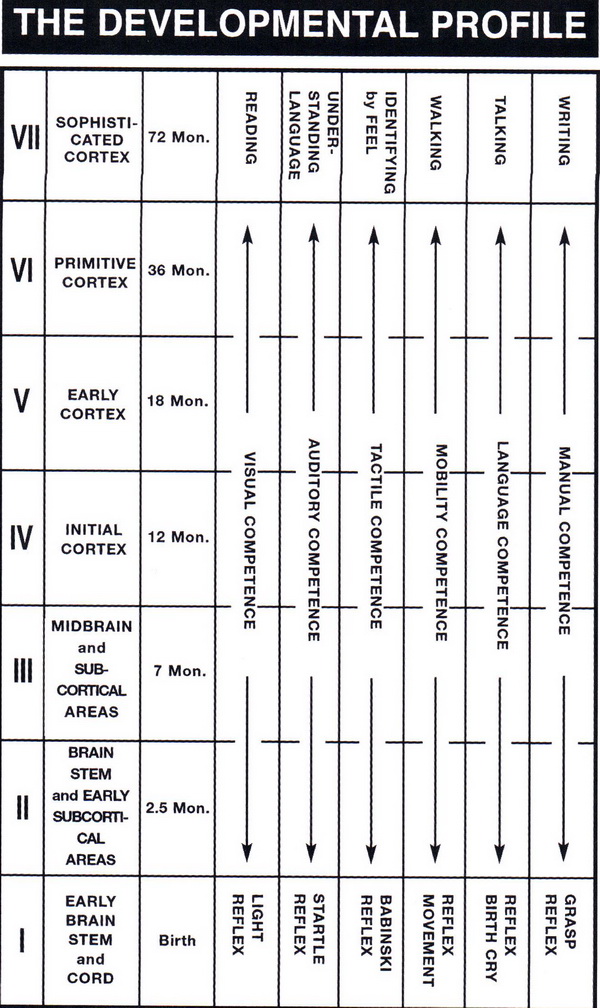

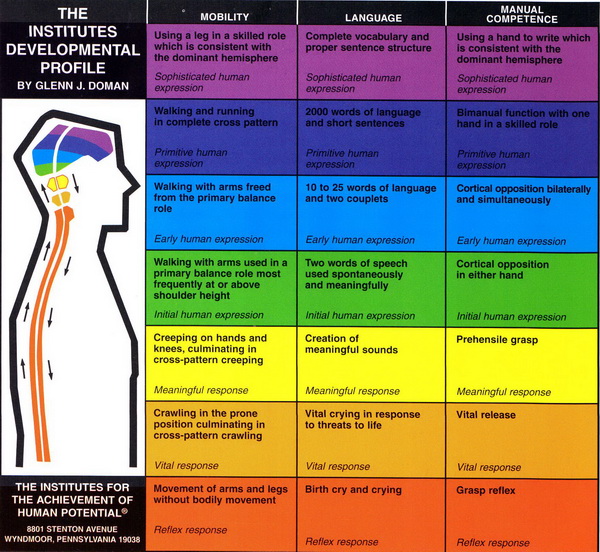

If the alarm clock theory were true, the healthy three-month-old Xingu baby should see the most, the full-term Chicago baby should see less, and the premature baby conceived the same day should see the least. In fact, the exact reverse is the case. How is this possible? Let's begin with our disadvantaged two-month-old baby who was born premature, ejected too soon from the friendly environment of his mother's uterus. We examine him at birth and find that in his case the prematurity has not affected his vision. He has a normal light reflex and sees light and dark. Our full-term Chicago baby, conceived on the same day, was born exactly two months later than our disadvantaged premature baby. We examine him and find that he too has normal vision. He has a light reflex and therefore sees light and dark. Both of these babies have the same "alarm clock" age. Based on the instant of conception, they are exactly the same age. At birth the full-term baby sees only light and dark while the disadvantaged premature baby (now two months old) already sees outlines and silhouettes, which is normal for a healthy two-month-old baby. We have seen this over and over. What does it mean? Why does the disadvantaged premature baby now see outlines while the full-term baby, the exact same age from conception, only sees light and dark? It is obvious, isn't it? The disadvantaged child has had a world to see for two whole months, while the advantaged child has not. Nobody ever read a book who didn't have a book to read. Nobody ever played a violin who didn't have a violin to play. Nobody ever swam who didn't have water in which to swim. Nobody ever saw a world who didn't have a world to see. It takes a month or two of seeing to grow the visual pathway of the brain to the stage at which it can begin to sort out what it sees. What about our three-month-old Xingu baby in the great savannahs of Brazil? These people were still so isolated 40 years ago that the legendary Villas-Boas brothers were the only outsiders who had ever seen them. So when The Institutes team arrived in 1966, we were the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth people outside of their own culture who had ever met and lived with them. Our Xingu baby is something in excess of three months old. He was raised with his Xingu tribe in the Mato Grosso of Brazil Centrale. If the model of the preset alarm clock were true, then surely our three-month-old Xingu baby would be able to see better than the disadvantaged premature baby or the full-term newborn. The reality is just the opposite. The disadvantaged, two-month premature baby will see the most. The advantaged newborn will, within a few days, see less. Our Xingu baby will see nothing at all. How can this be so? In the absence of appropriate opportunity in which to see, the passage of time is not an advantage. It is, in fact, a disadvantage. What happened to our little Xingu baby? He was a very beautiful baby, as are all Xingu babies. His people live in very large grass huts that have no windows and only one very small opening. These small openings serve to protect those who live within. It is impossible to enter a Xingu home without bending and bowing one's head. Intruders are easily dealt with by a blow to the head. The result is that Xingu huts are very, very dark. Indeed, there is almost no light at all inside the hut. When a Xinguano baby is born, for reasons known only to the Xinguanos, the baby is kept inside the hut for approximately the first year of life. When our team visited these beautiful people of the Mato Grosso, it was one of the few times in our lives that ignorance stood us in good stead. Being unaware of this custom, we asked a family with a baby, who was at least three months of age, if we could see him and photograph him. So mother and father brought baby out into the sunlight so we could get better photos of the baby. We examined his stage of development in terms of sight, hearing, and touch. He had a light reflex, but saw only light and dark. At three months of age he demonstrated no ability to see outline or detail. How could it have been otherwise? During this year the babies are not brought outside into the light at all. As a result of this custom, the babies cannot see when they are finally brought out of the huts. They have a light reflex, which is to say their pupils constrict in the presence of light as do a newborn baby's pupils, but beyond this they cannot see. So our three-month-old Xinguano baby was the oldest of the three chronologically, but in the sense of his visual development he was at the stage of a newborn. The premature disadvantaged baby has had two whole months in which to see before he was even scheduled to be born. He is chronologically the youngest from conception but he has had two months more stimulation than the well newborn. He is visually a full five months ahead of the Xinguano baby. He has the visual age of a two-month-old. This is because there is no preset alarm clock. The brain grows by use, not by a preordained timetable. Consider three families living side-by-side in suburbia. In one lives the Green family, in the next the Brown family, and in the last the White family. On the exact same day, each mother gives birth to a baby. Five weeks later, Mr. Green comes home and Mrs. Green says, "Guess what? The baby followed me with his eyes this morning. He was lying on his belly in bed and when I walked in between him and the window and it was very clear that he could see me even though I was across the room." And Dad says, "Is that all?" Mother says, "Wait a minute. He's five weeks old and our pediatrician says babies don't follow visually until they are ten weeks old. We have a very bright baby." Ten weeks after the babies are born, Mr. Brown comes home and Mrs. Brown says, "Hey, guess what? The baby followed me with his eyes today." And Dad says, "Is that all?" Mother says, "He is ten weeks old today and that's exactly when a baby is supposed to be able to follow with his eyes. We have a nice healthy baby." Fifteen weeks after the babies are born, Mr. White comes home and Mrs. White says, "Honey, we have to have a talk tonight." Since her tone is decidedly serious Dad says, "It's about money; let's talk now." Mother says, "No, it's not about money; it's much more important than that. It's about the baby. You know our baby is fifteen weeks old today and he still does not follow me with his eyes. And Dad says, "Is that all?" Mom says, "Wait a minute; he should have started to do that five weeks ago. Our baby's got a problem." Each of these mothers has come to a conclusion. Mrs. Green concludes that she has a very, very bright baby. Mrs. Brown concludes that she has a nice normal, healthy baby And Mrs. White concludes that her baby has a problem. And they are right, all three of them. But to what do they attribute it? Mrs. Green says to herself "I'm bright, my husband is bright, so we have a nice bright baby." Mrs. Brown says to herself, "I'm normal, my husband is normal, we both come from very normal families, so we have a nice normal baby." Mrs. White says to herself, "I'm absolutely normal and so is my husband, but I am not so sure about my husband's family. He had an Aunt Mabel who. . ." Basically, all three mothers assume that their babies are the way that they are for predetermined genetic reasons. But their three very different babies are not a product of genetic differences. Each of them is a product of their environment. The Green baby is a product of an enriched environment (even though in the Green family this happens to have been a happy accident). The Brown baby is a product of a visually average environment, and this too is an accident. The White baby is a product of an environment very low in visual stimulation. Unhappily this too is an accident. How very sad that we raise our children by accident. We feed their stomachs with the best food we can buy. We feed their brains by accident. We should above all other things give our babies the most important of all rights, the right to achieve their full human potential. And that, after all, is why you are reading this book. This book will show you how to grow your precious baby's brain, rather than waiting for the non-existent preset alarm clock to ring. Remember: The brain grows by use. In the case of the Green, Brown, and White families, the difference was in the stimulation of the visual pathways of the brain, which combined with the other pathways, actually comprise the brain. Each of the three babies is a product of how many times mother or father turned the light on and off. The sun comes up and the sun goes down. That's two stimuli for the baby. Beyond that, what's critical is how many times the "accident" of the light reflex occurs. When we turn the lights on in a dark room this stimulates the light reflex. The pupil will reflexively constrict in the presence of light and will dilate in the darkness. In most households this happens several times a day by accident. What father in history ever came home and said to his wife, "How many times did you turn the light on and off for the baby today?" But in the households of our families at The Institutes for The Achievement of Human Potential, that is exactly what happens. Fathers and mothers of blind, brain-injured children arrange for this "accident" to happen hundreds of times a day so that their blind children can develop, improve, or strengthen their light reflex, which is the first all-important step to being able to see. Fathers and mothers of well newborn babies arrange for this "accident" to happen dozens of times a day so that their well babies can improve and strengthen their light reflex and thereby gain the ability to see more rapidly. The importance of the well baby gaining the ability to see more rapidly is not simply so we can say, "How nice. He is growing faster than other babies his age." What good is that to the baby? The significance of gaining the ability to see earlier is far greater. The average baby is trapped in a visually ordinary room at the very moment when his brain is growing at its fastest rate. He is capable of taking in a tremendous amount of information but his visual pathway is not sufficiently developed to do so. The newborn who is stimulated, and thereby gains the ability to see weeks or even months earlier, has the wonderful opportunity to see everything that is around him during the period when his brain is growing so very rapidly. This visual ability then leads to the maturation of other pathways. Once he can see, he begins to understand more easily what we are saying to him. When he can see, his need to move is hugely increased. As a result, he tries harder to move and moves more. This movement both stimulates his sense of touch and helps to further develop his vision. His increased movement helps his chest to grow and as a result his respiration improves. This better respiration allows him to make sounds more easily so he can communicate his needs better. Thus begins a happy cycle of events, each one touching off yet another spark, each spark igniting yet another new ability. The more the brain is used the more it grows, and the more capable the baby becomes. This is the very definition of using the brain. This stimulation should be done on purpose, not by accident. The brain-injured child cannot afford to be stimulated by accident and, in truth, neither should the well newborn baby. The ability of the child is a product of stimulation and opportunity, not of a preset alarm clock or a predetermined genetic design. The reality of how the brain really develops turns out to be much better than the old idea of how the brain develops. The truth turns out to be much better than the fiction. Here we have seen how the visual pathway begins to grow by use. The brain is composed of six pathways that all grow by use. It's time to have a look at what those six pathways are. 7. The Institutes Developmental Profile. The Institutes Developmental Profile is a delineation of the significant stages of development that normal children pass through as they progress from birth to six years of age. It reflects progressive brain development. The Profile was developed after years of research and study of how children develop. We found that there are six abilities that characterize human beings and make them different from every other creature. These six functions are unique to human beings and all of them are functions of our unique cerebral cortex. Three of these functions are motor in nature, and they are entirely dependent upon the other three, which are sensory in nature. The three unique motor functions of all human beings are: 1. To walk and run in an upright position and in a true cross pattern (with opposite limbs moving together). 2. To speak in a complex symbolic vocal language invented and maintained by agreement and convention, such as English, Chinese, Spanish, Japanese, Italian, etc. 3. To write that invented, symbolic language by opposing thumb to forefinger. These three motor functions are absolutely unique to human beings and each is a function of the unique human cortex. These three motor skills are based on three unique sensory skills: 1. To see in such a way as to read the invented, symbolic language. 2. To hear in such a way as to understand that invented, symbolic language. 3. To feel in such a way as to be able to identify an object by touch alone and without confirming what it is by seeing, hearing, smelling, or tasting it. Each of these three sensory functions is unique to human beings and each is a function of our unique human cortex. After studying the early development of both brain-injured and well children, we found that each of these six functions developed through seven stages, beginning at birth and ending at six years of age. The seven stages of function correspond to seven stages of development of the brain. This occurs as different parts of the brain, which all exist at birth, develop and become functional.

We found that in average children these stages become functional at approximately the same time on the road to reaching each of the six functions. These seven critical periods, though highly variable, are, roughly: Birth 2.5 months 7 months 12 months 18 months 36 months 72 months With these pieces of the puzzle in place, it was possible to create a chart that shows the six vital and unique human functions and the seven stages at which they occur in a well child (see Figure 7.1). Once we had determined the significant stages that a baby must go through in order to complete his development, we needed to determine which functions are critical to human growth and development. This involved careful observation of hundreds of well babies at all stages of development. This study has spanned the last fifty years and continues to the present day. If The Institutes are remembered a hundred years hence it will more than likely be because of The Institutes Developmental Profile, which is the fruit of much of our labor. This Profile is a description of the growth and development of the human brain from birth to the point of maturation of the brain at six years of age. It is a no-nonsense document that is designed to be clear and straightforward so that any parent can study it and, what is much more important, use it easily. The challenge of creating the Developmental Profile was to decide not what to include but rather what to exclude. There are literally thousands of events that take place during the first six years of development. Gesell and his staff spent years cataloging those events. It was a monumental task. Essentially they had documented everything that a child did in those all important years between birth and five years of age.

Figure 7.1 Simplified Developmental Profile But we wanted to know a much more important thing: Of all the thousands of things a well child does in the process of growing up from birth to six, which things matter? In short, of the multitude of things that a baby does, which things are causes and which things simply results? Which would prevent him from developing normally if they were removed from his life? Each of these seven stages of development are the responsibility of a different stage of the brain. While all these stages of the brain exist in the newborn at birth, they become functional in successive order, from the lowest stage at birth to the highest stage of development at six years of age in the average child. Then we needed to add: 1. A diagram of the human brain with its successive stages of development. 2. The specific brain function itself in each of the forty-two blocks. 3. A color code to distinguish each of the brain stages. Thus a child's progress can be plotted, stage by stage and column by column on the Profile. This enables parents to ascertain their child's correct overall neurological age and handle any weak points that are found. Actually the Profile gives us six neurological ages: a visual age, an auditory age, a tactile age, a mobility age, a language age, and a manual age.

Mother evaluates her baby in each of the six columns to find out which abilities in each area her baby has and which abilities he does not have. A line is then drawn across the top of the highest stage that the baby has achieved in each of the six columns. Parents sometimes expect that the highest stage will be the same in all six columns but this is seldom the case. The sensory side of the Profile is, by necessity, higher than the motor side. The child must gain a good bit of sensory input before that input will become motor output. In short, the information must go into the brain before we can expect it to come out. For this reason the motor side of the Profile will often be somewhat behind the sensory side. It is possible that a lower area in some of the columns is not perfect. It is possible to achieve a higher stage before all lower stages are perfect. However, the child will not achieve perfection at the top of the Profile (Stage VII) until he has perfected all lower stages. Finally, we had what has become known as The Institutes Developmental Profile (see Figure 7.2). As we have said, in the past it was theorized that this progression was a predestined and unalterable fact that resulted from predetermined genetic inheritance superimposed upon a rigid schedule of time and sequence. We have shown this to be untrue. The order in which the significant stages of development take place (visual, auditory, and tactile on the sensory side of the Profile, and mobility, language, and manual development on the motor side) is a function of the brain's development as successively higher stages are brought into play. The timetable is highly variable and depends upon two things:

Figure 7.2 The Institutes Developmental Profile 1. The frequency, intensity, and duration of the stimuli provided to the brain by the child's environment. 2. The neurological condition of the child. The Developmental Profile details the development of every child from birth to six years of age, when neurological development is effectively complete. In creating this Profile we have not used the conventional psychological, developmental, or medical terms. These terms often represent an observable chronology that accompanies a child's development, and while these events may be true, they are nonetheless not significant to his development. In addition, many of these terms mean different things to different people. That diminishes their usefulness as reliable tools, and it accounts for widely differing reports by v Date: 2015-02-28; view: 818

|

Figure 2.1 Movement without mobility

Figure 2.1 Movement without mobility Figure 2.2 Crawling

Figure 2.2 Crawling Figure 2.3 Creeping

Figure 2.3 Creeping Figure 2.4 Walking

Figure 2.4 Walking