CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

Who Uses CAPTCHA

One common application of CAPTCHA is for verifying online polls. In fact, a former Slashdot poll serves as an example of what can go wrong if pollsters don't implement filters on their surveys. In 1999, Slashdot published a poll that asked visitors to choose the graduate school that had the best program in computer science. Students from two universities -- Carnegie Mellon and MIT -- created automated programs called bots to vote repeatedly for their respective schools. While those two schools received thousands of votes, the other schools only had a few hundred each. If it's possible to create a program that can vote in a poll, how can we trust online poll results at all? A CAPTCHA form can help prevent programmers from taking advantage of the polling system.

Registration forms on Web sites often use CAPTCHAs. For example, free Web-based e-mail services like Hotmail, Yahoo! Mail or Gmail allow people to create an e-mail account free of charge. Usually, users must provide some personal information when creating an account, but the services typically don't verify this information. They use CAPTCHAs to try to prevent spammers from using bots to generate hundreds of spam mail accounts.

Ticket brokers like TicketMaster also use CAPTCHA applications. These applications help prevent ticket scalpers from bombarding the service with massive ticket purchases for big events. Without some sort of filter, it's possible for a scalper to use a bot to place hundreds or thousands of ticket orders in a matter of seconds. Legitimate customers become victims as events sell out minutes after tickets become available. Scalpers then try to sell the tickets above face value. While CAPTCHA applications don't prevent scalping, they do make it more difficult to scalp tickets on a large scale.

Some Web pages have message boards or contact forms that allow visitors to either post messages to the site or send them directly to the Web administrators. To prevent an avalanche of spam, many of these sites have a CAPTCHA program to filter out the noise. A CAPTCHA won't stop someone who is determined to post a rude message or harass an administrator, but it will help prevent bots from posting messages automatically.

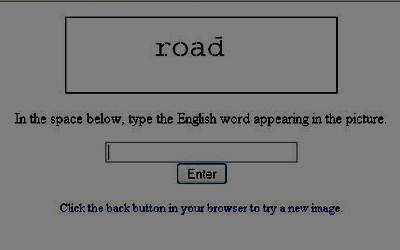

The most common form of CAPTCHA requires visitors to type in a word or series of letters and numbers that the application has distorted in some way. Some CAPTCHA creators came up with a way to increase the value of such an application: digitizing books. An application called reCAPTCHA harnesses users responses in CAPTCHA fields to verify the contents of a scanned piece of paper. Because computers aren't always able to identify words from a digital scan, humans have to verify what a printed page says. Then it's possible for search engines to search and index the contents of a scanned document.

Here's how it works: First, the administrator of the reCAPTCHA program digitally scans a book. Then, the reCAPTCHA program selects two words from the digitized image. The application already recognizes one of the words. If the visitor types that word into a field correctly, the application assumes the second word the user types is also correct. That second word goes into a pool of words that the application will present to other users. As each user types in a word, the application compares the word to the original answer. Eventually, the application receives enough responses to verify the word with a high degree of certainty. That word can then go into the verified pool.

It sounds time consuming, but remember that in this case the CAPTCHA is pulling double duty. Not only is it verifying the contents of a digitized book, it's also verifying that the people filling out the form are actually people. In turn, those people are gaining access to a service they want to use.

Next, we'll take a look at the process that goes into creating a CAPTCHA.

PREPACKAGED

Installing a CAPTCHA on your Web site is as easy as copying a few lines of code into your site's HTML page. And it won't even cost you a dime -- many CAPTCHA applications are free.

CAN YOU HEAR ME NOW?

In many ways, audible CAPTCHAs are similar to visual ones. In a database approach, the CAPTCHA creator must pre-record a person or computer speaking every series of characters and then match them with the right solution. With a randomized approach, the creator pre-records each character individually and the application strings the characters together randomly to create CAPTCHAs.

Creating a CAPTCHA

The first step to creating a CAPTCHA is to look at the different ways humans and machines process information. Machines follow sets of instructions. If something falls outside the realm of those instructions, the machine isn't able to compensate. A CAPTCHA designer has to take this into account when creating a test. For example, it's easy to build a program that looks at metadata -- the information on the Web that's invisible to humans but machines can read. If you create a visual CAPTCHA and the image's metadata includes the solution, your CAPTCHA will be broken in no time.

Similarly, it's unwise to build a CAPTCHA that doesn't distort letters and numbers in some way. An undistorted series of characters isn't very secure. Many computer programs can scan an image and recognize simple shapes like letters and numbers.

One way to create a CAPTCHA is to pre-determine the images and solutions it will use. This approach requires a database that includes all the CAPTCHA solutions, which can compromise the reliability of the test. According to Microsoft Research experts Kumar Chellapilla and Patrice Simard, humans should have an 80 percent success rate at solving any particular CAPTCHA, but machines should only have a 0.01 success rate [source: Chellapilla and Simard]. If a spammer managed to find a list of all CAPTCHA solutions, he or she could create an application that bombards the CAPTCHA with every possible answer in a brute force attack. The database would need more than 10,000 possible CAPTCHAs to meet the qualifications of a good CAPTCHA.

Other CAPTCHA applications create random strings of letters and numbers. You aren't likely to ever get the same series twice. Using randomization eliminates the possibility of a brute force attack -- the odds of a bot entering the correct series of random letters are very low. The longer the string of characters, the less likely a bot will get lucky.

CAPTCHAs take different approaches to distorting words. Some stretch and bend letters in weird ways, as if you're looking at the word through melted glass. Others put the word behind a crosshatched pattern of bars to break up the shape of the letters. A few use different colors or a field of dots to achieve the same effect. In the end, the goal is the same: to make it really hard for a computer to figure out what's in the CAPTCHA.

Designers can also create puzzles or problems that are easy for humans to solve. Some CAPTCHAs rely on pattern recognition and extrapolation. For example, a CAPTCHA might include a series of shapes and ask the user which shape among several choices would logically come next. The problem with this approach is that not all humans are good with these kinds of problems and the success rate for a human user can drop below 80 percent.

Next, we'll take a look at how computers can break CAPTCHAs.

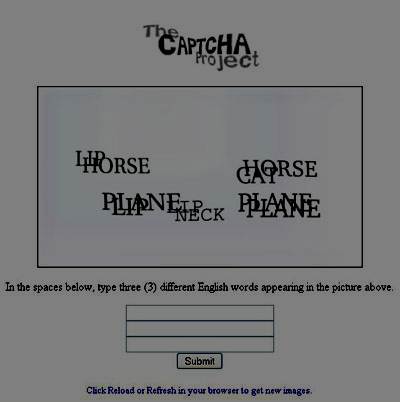

The Gimpy CAPTCHA displays 10 words, but you only have to type three in correctly to pass the test.

Breaking a CAPTCHA

The challenge in breaking a CAPTCHA isn't figuring out what a message says -- after all, humans should have at least an 80 percent success rate. The really hard task is teaching acomputer how to process information in a way similar to how humans think. In many cases, people who break CAPTCHAs concentrate not on making computers smarter, but reducing the complexity of the problem posed by the CAPTCHA.

Let's assume you've protected an online form using a CAPTCHA that displays English words. The application warps the font slightly, stretching and bending the letters in unpredictable ways. In addition, the CAPTCHA includes a randomly generated background behind the word.

A programmer wishing to break this CAPTCHA could approach the problem in phases. He or she would need to write an algorithm -- a set of instructions that directs a machine to follow a certain series of steps. In this scenario, one step might be to convert the image in grayscale. That means the application removes all the color from the image, taking away one of the levels of obfuscation the CAPTCHA employs.

Next, the algorithm might tell the computer to detect patterns in the black and white image. The program compares each pattern to a normal letter, looking for matches. If the program can only match a few of the letters, it might cross reference those letters with a database of English words. Then it would plug in likely candidates into the submit field. This approach can be surprisingly effective. It might not work 100 percent of the time, but it can work often enough to be worthwhile to spammers.

What about more complex CAPTCHAs? The Gimpy CAPTCHA displays 10 English words with warped fonts across an irregular background. The CAPTCHA arranges the words in pairs and the words of each pair overlap one another. Users have to type in three correct words in order to move forward. How reliable is this approach?

As it turns out, with the right CAPTCHA-cracking algorithm, it's not terribly reliable. Greg Mori and Jitendra Malik published a paper detailing their approach to cracking the Gimpy version of CAPTCHA. One thing that helped them was that the Gimpy approach uses actual words rather than random strings of letters and numbers. With this in mind, Mori and Malik designed an algorithm that tried to identify words by examining the beginning and end of the string of letters. They also used the Gimpy's 500-word dictionary.

Mori and Malik ran a series of tests using their algorithm. They found that their algorithm could correctly identify the words in a Gimpy CAPTCHA 33 percent of the time [source: Mori and Malik]. While that's far from perfect, it's also significant. Spammers can afford to have only one-third of their attempts succeed if they set bots to break CAPTCHAs several hundred times every minute.

You'd think that the inventors of CAPTCHA would be upset that their hard work is being picked apart by hackers, but you'd be wrong. Find out why in the next section.

ELECTRONIC EARS

Audio CAPTCHAs aren't foolproof either. In the spring of 2008, there were reports that hackers figured out a way to beat Google's audio CAPTCHA system. To crack an audio CAPTCHA, you have to create a library of sounds representing each character in the CAPTCHA's database. Keep in mind that depending on the distortion, there might be several sounds for the same character. After categorizing each sound, the spammer uses a variation of voice-recognition software to interpret the audio CAPTCHA [source: Networkworld].

Hackers have found ways to teach computers how to recognize the text in EZ-Gimpy CAPTCHAs.

CAPTCHA and Artificial Intelligence

Luis von Ahn of Carnegie Mellon University is one of the inventors of CAPTCHA. In a 2006 lecture, von Ahn talked about the relationship between things like CAPTCHA and the field of artificial intelligence (AI). Because CAPTCHA is a barrier between spammers or hackers and their goal, these people have dedicated time and energy toward breaking CAPTCHAs. Their successes mean that machines are getting more sophisticated. Every time someone figures out how to teach a machine to defeat a CAPTCHA, we move one step closer to artificial intelligence.

As people find new ways to get around CAPTCHA, computer scientists like von Ahn develop CAPTCHAs that address other challenges in the field of AI. A step backward for CAPTCHA is still a step forward for AI -- every defeat is also a victory [source: Human Computation].

But what about Web administrators? They might not find von Ahn's philosophy to be nearly as attractive. From their perspective, they still have to deal with a massive problem -- spammers and hackers. People who maintain Web sites or create online polls need to be aware that several CAPTCHA systems are no longer effective. It's important to do a little research on which CAPTCHA applications are still reliable. And it's equally important to keep up to date on the subject. If one CAPTCHA system fails, the administrator might need to remove the code from his or her site and replace it with another version.

As for CAPTCHA designers, they have to walk a fine line. As computers become more sophisticated, the testing method must also evolve. But if the test evolves to the point where humans can no longer solve a CAPTCHA with a decent success rate, the system as a whole fails. The answer may not involve warping or distorting text -- it might require users to solve a mathematical equation or answer questions about a short story. And as these tests get more complicated, there's a risk of losing user interest. How many people will still want to post a reply to a message board if they must first solve a quadratic equation?

Eventually, we might reach a point where computers and humans perceive puzzles the same way. If that happens, tests like CAPTCHA will become useless lines of code. Until then, we'll just have to squint (or listen) carefully while trying to decipher CAPTCHA codes.

To learn more about Web site security and related topics, test out the links on the next page.

SHALL WE PLAY A GAME?

Luis von Ahn has a reputation for harnessing human computation as a way to advance computer technology. How do you convince people to help you make machines smarter? Turn it into a game! Here are a few of the games von Ahn has worked on that make computer programs more effective:

- The ESP Game, which pairs players up, shows each player a picture, and challenges the players to come up with the same tags to describe that picture. Each verified tag helps categorize the photo for search engines.

- Then there's Verbosity. One player describes a word to another player using a series of clues. The other player must guess the correct word.

- The Matchin game presents the same two photos to two different players. Each player picks the photo that he or she likes the most. Both players earn points for every match. As the game gathers results, it categorizes photos from most attractive to least attractive.

Date: 2015-02-28; view: 2873

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| How CAPTCHA Works | | | How English are you? |