CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

PROSPERITY AND CIVIL RIGHTS 3 pageElsewhere in the region, the pattern of settlement is less varied. Black Americans are an important force in all the region's cities. But families of Italian and Eastern European descent are more apparent in urban areas outside New York City. Recently the region's heavy industries have fallen on hard times. Like the factories of New England, these industries have found it hard to compete with cheaper goods made elsewhere. Even so, the Middle Atlantic region has managed to propser. It has done so partly by building new industries such as drug manufacturing and communications. THE SOUTH If all regions of the United States differ from one another, the South could be said to differ most. At several times in the nation's history, in fact, the region has shown a pride in its differences that has approached defiance and even blossomed into southern nationalism. The South was devastated socially and economically in the mid-19th century by the American Civil War. Nevertheless, it has remained distinct, and it played a major role in forming the character of America from before the War of Independence to the Civil War. Perhaps the most basic difference between the South and other regions is geographic. Southerners generally enjoy more ways free of frost than northerners do. The South also has more rainfall than the West. A southerner once described his region as a land of yellow sunlight, clouded horizons and steady haze. He thought the climate an inspiration for the southern spirit of romance. The first Europeans to settle this sultry region were, as in New England, mostly English Protestants. These were Anglican rather than Calvinist, however, and few of them came to America in search of religious freedom. Most sought the opportunity to farm the land and live in reasonable comfort. Their early way of life resembled that of English farmers, whom they often imitated, in the days before the Industrial Revolution. The South emulated England as much as New England prided itself on its distinction from it. In coastal areas some settlers grew wealthy by raising and selling crops such as tobacco and cotton. In time some of them established large farms, called plantations, which required the work of many laborers. To supply this need, plantation owners came to rely on slaves shipped by the Spanish, Portuguese and English from Africa. Slavery is unjust. The fact remains, however, that it became a part of southern life in the United States, as it did throughout Central and South America. Nevertheless, the great majority of southern agriculture was carried out on single family farms, just as it was in the North, and not on large plantations. The South played a major role in the American Revolution of the 1770s. Soon afterward, it provided the young United States with four of its first presidents, including George Washington. After about 1800, however, the apparent interests of the manufacturing North and the more agrarian South began to diverge in obvious ways. The North became more and more industrial, while the South was wedded to the land. In the cotton fields and slave quarters of the region, black Americans created a new folk music, Negro spirituals. These songs were religious in nature and some bore similarities to a later form of black American music, jazz. As the century wore on, slavery became a steadily more serious problem for the South. "Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate," asserted Virginia's Thomas Jefferson, than that black people "are to be free." As the United States expanded, Jefferson's words came to seem an increasingly accurate forecast. Nonetheless, many southern leaders defended the slave system; to them, an attack on slavery seemed an unwarranted attack on the southern way of life. The issue led to a national political crisis in 1860. Eleven southern states from Virginia to Texas left the federal union to form a nation of their own. The result was the most terrible war in the history of the United States, the Civil War (1861-1865). With all its largest and most important cities in ashes, the South finally surrendered. It was then forced to accept many changes during the period of Reconstruction (rebuilding), which lasted officially until 1877. Many of the subsequent political alignments in the United States stem from the passions and perceptions of this period. The leaders of Reconstruction were members of the Republican party in the national government. They not only ended slavery, but planned to put black southerners on an equal footing with whites and to redistribute old plantation lands. White southerners opposed and resented such efforts and the Republicans who supported them. For the next century, white southerners voted for the Democratic party with such fervor that their region became known as the "Solid South." For a time, black Americans gained a voice in southern government. By the end of the 19th century, though, they faced a new barrier to equality. Southern towns and cities refined and legalized the practice of racial segregation. Blacks attended separate schools from whites, rode in separate railroad cars and even drank at separate water fountains. Gradual change did come, however, and this time from within. It began in about 1900 as the region turned to manufacturing of many different kinds. By 1914, the South had at least 15,000 factories and the number was increasing, although the population remained largely rural. At about the same time, many black Americans began moving from southern farms to the cities of the North. The pace of change quickened throughout the first half of this century. Coastal sections of Florida and Georgia became vacation centers for Americans from other regions. In cities such as Atlanta, Georgia, and Memphis, Tennessee, the populations soared. For decades some southern leaders had been speaking of a "New South." Now it seemed, a "New South" was coming into being. The greatest change of all took place after the return of the veterans of World War II. In the 1950s and 1960s, after years of black protest, Supreme Court rulings and the passage of sweeping civil rights legislation, the obvious forms of segregation came to an end. For the first time since Reconstruction, blacks gained a greater voice in local government throughout the South. Although their struggle for equality had not ended, it was finally having an effect. All these changes produced many tensions among southerners. In the period between the first and second World Wars, a southern literary movement arose which gave the nation some of its greatest writers of this century. Novelists such as Thomas Wolfe, Robert Penn Warren, Carson McCullers and William Faulkner spun stories of southern pride and displacement. Playwrights such as Tennessee Williams built dramas around the same themes. Why this literary outpouring? Georgia's Flannery O'Connor, a major novelist, once explained it this way: "When a southerner wants to make a point, he tells a story; it's actually his way of reasoning and dealing with experience." Today sleek, new, high-rise buildings crowd the skylines of cities such as Atlanta, Georgia and Little Rock, Arkansas. Late model cars cover the parking lots of iron mills in Birmingham, Alabama, and oil refineries in Houston, Texas. Along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of Florida, builders put up new apartments for vacationers from almost everywhere. The South is booming as never before. THE MIDWEST For the first 75 years of American history, the area west of the Appalachian mountains was not really a region at all. It was a beacon summoning the nation to its future and, later, measuring how far the United States had come. In what are now the states of Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, people moving to the frontier found gently rolling countryside. If tickled with a hoe, they said, the land would laugh with the harvest. As they moved west across the Mississippi River, though, the land became flatter and more barren. Here the horizons were so broad that they seemed to swallow travelers in space. The key to the region was the mighty Mississippi itself. In the early years it acted as a lifeline, moving settlers to new homes and great amounts of grain and other goods to market. In the 1840s, Samuel Clemens spent his boyhood beside the Mississippi. Writing under the name of Mark Twain, he later described the wonders of rafting on the river in his novel, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. As the Midwest developed, it turned into a cultural crossroads. The region attracted not only easterners but also Europeans. A great many Germans found their way to eastern Missouri and areas farther north. Swedes and Norwegians settled in western Wisconsin and many parts of Minnesota. The Irish came and so did Finns, Poles and Ukrainians. As late as 1880, 73 percent of the residents of Wisconsin had parents who had been born in foreign countries. Gradually, the Midwest became known as a region of small towns, barbed-wire fences to keep in livestock, and huge rectangular fields of wheat and corn. Midwestern farmers raised more than half of the nation's wheat and oats and nearly half of its cattle and dairy cows. A hectare of land in central Illinois could produce twice as much corn as a hectare of fertile soil in Virginia. For these reasons, the region was nicknamed the nation's breadbasket Midwesterners are praised as being open, friendly, straightforward and "down-to-earth." Their politics tend to be cautious, though the caution could sometimes be peppered with protest. The region gave birth to the Republican party, formed in the 1850s to oppose the extending of slavery into western lands. The Midwest also played an important role in the Progressive Movement at the turn of this century. Progressives were farmers, merchants and other members of the middle class who generally sought less corrupt, fairer and more efficient government. Perhaps because of their location, midwesterners lacked the interest in foreign affairs shown by many Americans in the financial and immigration centers of Boston and New York. In the years after World War I, many leaders argued that the nation should stay out of overseas quarrels. This movement, called isolationism, died with Japan's surprise attack on the United States in 1941. Yet the Midwest is still remembered as the region least ready to rally to foreign causes. Today the hub of the region remains Chicago, Illinois, the nation's third largest city. This major Great Lakes port has long been a connecting point for rail lines and air traffic to far-flung parts of the nation. At the heart of the city stands the world's tallest building, Sears Tower. This skyscraper soars a colossal 1,454 feet (447 meters) into the air. THE SOUTHWEST The Southwest differs from the Midwest in three primary ways. First, it is drier. Second, it is emptier. Third, the populations of several of the southwestern states comprise a different ethnic mix. Rain-laden winds blow across most of the region only in the spring. During that season, the rain may be so abundant that rivers rise over their banks. In summer and autumn, however, little rain falls in much of Arizona and New Mexico and the western sections of Texas. Only in the river valleys of those areas can any intensive farming take place. Partly because this region is drier, it is much less densely populated than the Midwest. Outside the cities, the region is a land of wide open spaces. One can travel for miles in some areas without seeing signs of human life. Parts of the Southwest once belonged to Mexico. The United States gained this land following a war with its southern neighbor between 1846 and 1848. Today three southwestern states lie along the Mexican border—Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. All have a larger Spanish-speaking population than other regions except southern California. THE WEST Americans have long regarded the West as a "last frontier." Yet California has a history of European settlement much older than that of most mid western states. Spanish priests and soldiers first set up missions along California's coast a few years before the start of the American Revolution. In the 19th century, California and Oregon entered the Union ahead of many states to the east. In the West, scenic beauty exists on a grand scale. All eleven states are partly mountainous, and in Washington, Oregon and northern California the mountains present some startling contrasts. To the west of the mountains, winds off the Pacific Ocean carry enough moisture to keep the land well watered. To the east, however, the land is very dry. Parts of western Washington receive 20 times the amount of rainfall received in eastern Washington. The wet climate near the coast supports great forests of trees such as redwoods and stately Douglas firs. In many areas the population is sparse. Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Utah and Idaho—the Rocky Mountain States—occupy about 15 percent of the nation's total land area. Yet these states, so filled with scenic wonders, have only about three percent of the nation's total population. Except for Hawaii, the westernmost states have all been settled primarily by people from other parts of the nation. Thus, the region has an interesting mix of ethnic groups. In southern California—also considered part of the Southwest—people of Mexican descent play a role in nearly every part of the economy. In the valleys north of San Francisco, Italian families loom large in the growing of grapes and the bottling and selling of California wine. Americans of Japanese descent traditionally managed truck farms in northern California and Oregon, and Chinese Americans were once mostly known as farmers, laborers and the owners of laundries and restaurants. In recent years large numbers of the younger generation have achieved positions of prominence in medicine, law, engineering scientific research, music and many other fields. In the 1980s, large numbers of people from Korea and Southeast Asia settled in California, mainly around Los Angeles. Hawaii is the only state of the Union where Asian-Americans outnumber residents of European stock. Among Asian-Americans, those of Japanese descent are the largest group. People of Chinese and Filipino ancestry are also well represented. New Englanders have left their mark on much of the West. Many northwesterners prize "Yankee" virtues such as shrewdness and thrift. In much of California, however, life is more flamboyant. Some observers trace this quality to the gambling instincts of the Gold Rush of 1848, which first brought many Americans west in search of gold discovered there. Others say that the Gold Rush did not last long enough to leave a lasting mark on the culture of the state. These observers claim that the California experience is mostly the result of a sunny climate and the self-confidence that comes of success. The success is not much debated. In 1860 El Pueblo de Nuestra Senora la Reina de los Angeles de Porciuncula was a hodgepodge of adobe huts on the edge of a sandy wilderness. A century and a quarter later, Los Angeles had become the second most populous city in the nation. To millions of people, the city means Hollywood, the center of the film industry. Yet Los Angeles also produces aircraft parts, electronic equipment and other products of today's technology. Fueled by growth in Los Angeles and smaller cities such as San Jose, California is now larger than every other state in size of population. Still the richness of America is not measured exclusively in numbers but in the diversity and resourcefulness of its people from all the various regions.

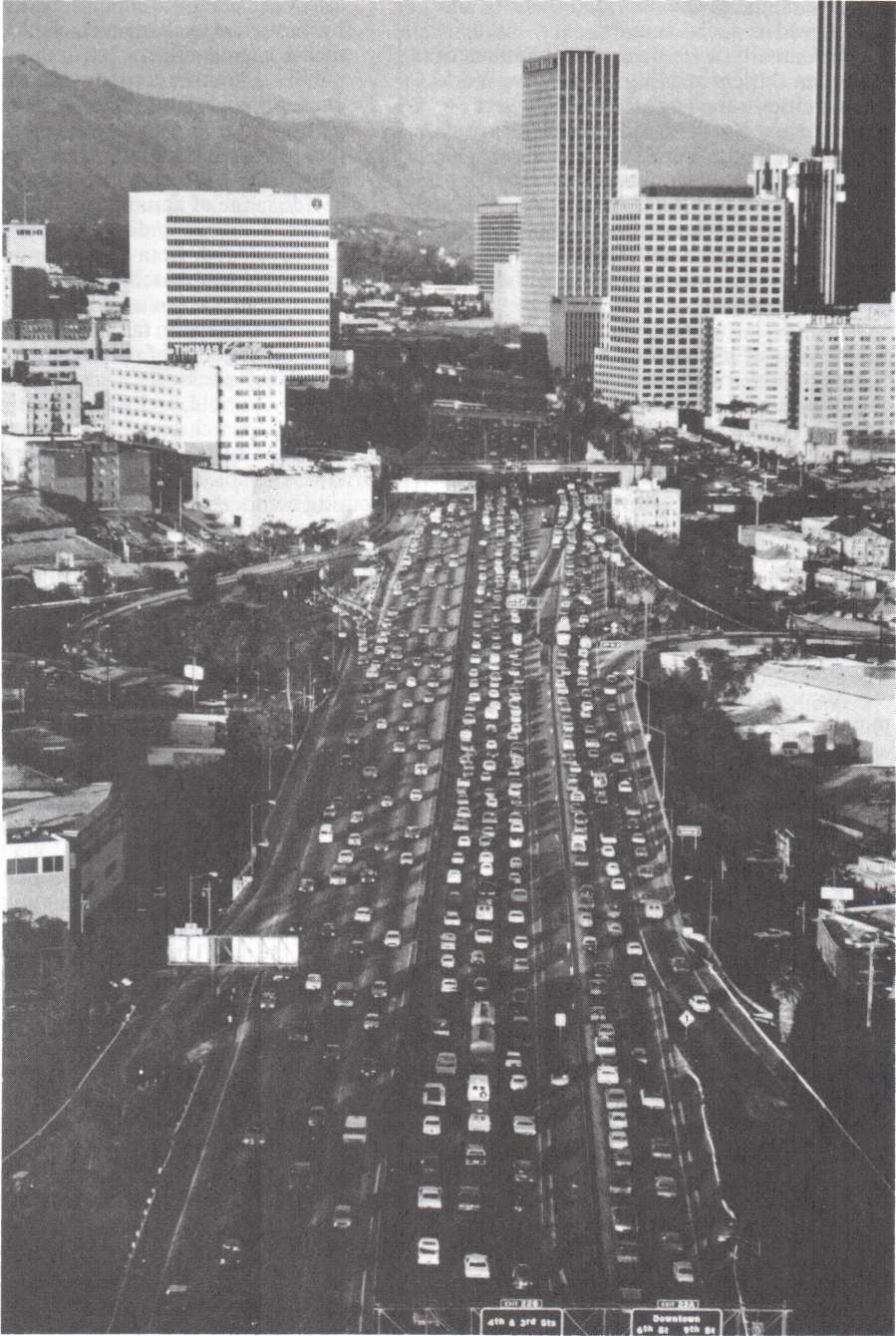

By Bruce Oatman (Fordham University) Three hundred years ago a handful of town dwellers lived in a few scattered locations along the Atlantic coastline of what is now the United States. In the early years of this century, over 50 percent of the population of the United States still lived in rural areas. Today, however, the United States is a nation of urban dwellers. Almost 80 percent of the national population lives either within the formal boundaries of cities or in the huge suburban rings (clusters of communities socially and economically connected to the cities) which surround them. More than two hundred of these metropolitan regions now make up the everyday setting of American life. The influence of cities in modern America is extensive. Thanks in part to urban-based national news media, in a country in which only two people in 100 now live on farms, the power of cities to influence life far beyond their borders is very great. From urban centers, through suburban communities, into the smallest and most distant rural villages flow many social and economic values, ways of making a living, clothing styles and manners, and a modern technological spirit. As a result, many of the once sharp distinctions that could be made between rural and urban ways of life no longer exist. The geography may differ between city and country, and social and political attitudes may still vary, but the forms

of living and working are remarkably similar. How did this come about and what does it mean for the quality of American life today? EARLY YEARS: 1625-1812 The original North American colonies were regarded by the mother countries of Britain, Holland and France primarily as sources of raw material from field, forest, ocean and mine, and as potential markets for finished goods manufactured in Europe. While this approach required rural and wilderness settlement, it was necessary, at the same time, to establish small towns in the colonies as administrative centers to control the emerging trans-Atlantic trade. These towns were gathering places for artisans and shopkeepers who served the agricultural hinterlands. In the large and frightening wilderness, the towns provided security and also served as social centers. Eventually, with increasing numbers of European settlers arriving in the New World, coastal cities—the largest of which were Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Charleston, South Carolina—came into being, and their economic and social influence stretched into extensive rural backlands. At the same time, as port cities, they rapidly grew to be flourishing centers of international commerce, trading with Europe and the Caribbean. By 1660, Boston contained about 3,000 people. One of its inhabitants described it as a "...metropolis...[with] two handsome churches, a market place and a statehouse. The town is full of good shops well furnished with all kinds of merchandise—artisans and tradesmen of all sorts." New York (then called New Amsterdam) was founded in 1625 by the Dutch West India Company, which exported furs, timber and wheat. Captured by the British in 1664, New Amsterdam was renamed New York. Because of its favorable geography, it soon became an important trading port. By 1775, its population was about 25,000. William Penn, who planned the city of Philadelphia, believed that a well-ordered city was necessary to economic growth and moral health. He wanted to build a "green country town" which would not be sharply cut off from the surrounding forest and farmlands. Inside the town were markets, residential housing, small factories, churches, public buildings, recreational areas and parks. Farming areas would be on the periphery but close enough to be accessible to the city dwellers. Penn's ideas were widely copied in his day. An echo of them can be heard in contemporary planned communities which preserve parks and open spaces within a town's boundaries. Most American towns of this early period featured open spaces alternating with built-up areas. Much free land was available, and, as fewer than 10 percent of the people lived in the towns, few opposed their growth. By the middle of the 18th century, however, many people opposed this growth because the towns had begun to seem too large and crowded. In 1753, the newspapers printed a debate which seems very similar to the arguments of today. The positive view of cities was expressed by a writer who argued that the economic specialization of cities led to increased wealth for both city and farm dwellers: "...different handicrafts ought to be done by different persons, that (such) work might be done to perfection, which would be a considerable profit to the country...and to those who are proficient in the handicrafts. [Specialization] would cause an extraordinary market for provisions of all kinds...." The contrary view of cities was expressed in an argument, dating back to antiquity, and reflecting a strong belief in the virtues of an agrarian life in the United States, which portrays cities as places which undermine self- sufficiency and encourage meaningless social activity and moral decay: "...Every town not employed in useful manufacture...is a dead weight upon the public.... When families collect themselves into townships they will always endeavor to support themselves by barter and exchange which can by no means augment the riches of the public.... Another consequence of the clustering into towns is luxury—a great and mighty evil, carrying all into...inevitable ruin." By 1750, the larger cities were dominated by a wide range of commercial and craft activities. A corresponding range of social groups developed: from an economically and socially dominant merchant and administrative class to a middle class of artisans, shopkeepers, farmers and smaller traders. On the edge of society, groups of the poor and dispossessed scrambled for an economic foothold, and were sometimes dependent upon charity. Culturally, the colonies were outposts of Britain. The colonial cities were visited by touring actors and musicians and enriched by the development of schools, libraries and lecture halls. All of this increased the differences between city and country life and contributed to the importance of the American city as an initiator of social change. In terms of administration, the development of towns created a dense web of social, economic and governmental structures and regulations. However, the forms of municipal government varied greatly from place to place. In New England, the town meeting prevailed. This was a gathering of all citizens to discuss common concerns, and was an outgrowth of Protestant leader John Calvin's ideas about providing for representative government in a religious community. This form of community government continues today in the small towns of the Northeast. Councilmen were first elected to govern New York City in 1684. In contrast, the city of Charles Town (now called Charleston), in South Carolina, had no local representatives, but was governed by the State Assembly. The War of Independence (1775-1783) was largely brought about by the grievances of city dwellers. Strict limitations imposed by the British on manufacture and trade, and the British Parliament's repeated levying of taxes without prior consultation with the colonists were widely perceived as unjust and punitive measures. Furthermore, one hundred years of inter-city trade had forged a sense of nationhood. The famous Boston Tea Party, during which colonists destroyed tea imported on British ships rather than pay taxes on it, expressed the colonists' frustration and their growing sense of national unity. The war secured political independence for the United States, but economically, the new nation was still dependent upon the trading patterns that had developed over a century. The country supplied raw material and imported finished goods. This situation lasted until the War of 1812 (with England), during which great suffering occurred as a result of the British blockade of American ports. Even those Americans who had earlier resisted the development of a larger manufacturing sector and the growth of cities now changed their minds. Thomas Jefferson, president of the United States from 1801 to 1809, had written in 1800 that, "I view great cities as pestilential to the morals, the health and the liberties of man." However, after 1812, he wrote, "We must now place the manufacturer by the side of the agriculturist." Economic growth and independence, were necessary to guarantee political liberty however undesirable the growth of manufacturing cities might be. Some of Jefferson's contemporaries had even earlier chosen to view the cities from the positive rather than the negative perspective and to turn their practical intelligence to the improvement of city life. Benjamin Franklin of Philadelphia was one of these: "I began now to turn my thoughts to public affairs, beginning with small matters—our city had the disgrace of suffering its streets to remain long unpaved so that it was difficult to cross them. By talking and writing on the subject, I was at length instrumental in getting the street paved with stones—all the inhabitants of the city were delighted." MIDDLE PERIOD: 1812-1918 At the time of the War of 1812, less than one in 10 Americans lived in cities. By the end of World War I (1914-1918), one in two did. In 1812, American cities had experienced little of the overcrowding and decay of European cities of that time. Within a few decades, however, the very rapid growth of urban population gave American cities all of the unpleasant qualities long associated with older cities everywhere. This growth can be traced to four causes: rapid industrialization, with its ever-increasing demand for workers; the relentless construction of roads and railways making easier the movement of goods and people from, to and through the urban manufacturing centers, a steady stream—at times a flood—of immigrants fleeing war, persecution and poverty in their countries of origin and concentrating in America's major ports of entry, and farm workers displaced by machinery or discouraged by low wages, making their way to a supposed brighter future in the cities. Boston's population increased from 43,000 in 1820 to 250,000 in 1870. New York's population went from 124,000 in 1820 to 942,000 in 1870; Philadelphia's population rose from 64,000 to 674,000 in the same period, and Chicago's population climbed from 0 to 299,000. During the same period, the ratio of urban dwellers in the much expanded national population rose from eight percent to 25 percent. This was also the period of westward migration, which settled the territory from Chicago to California. By the end of the 19th century, the United States was dotted with large and small cities. These were bound together in a continent-wide web of social and economic relations made possible by the building of road and rail systems. From the 1820s to the 1880s, changes occurred so rapidly that city governments struggled to cope with them. By 1830, New York had gained a reputation, which it still holds, as a place of great motion and constant activity. The city was considered to be the showcase of American modernism. At the same time, New York experienced archaic sanitation, typhoid and dysentery epidemics, contaminated water, severe poverty, insufficient housing and schools, and an overwhelming influx of immigrants. Juvenile crime was so widespread that in 1849 New York's police chief devoted his entire annual report to the subject. Garbage filled the streets and, until the 1860s, bands of pigs were typically let loose to roam as scavengers in all the larger cities. The immigrants came from practically every country and area of the world, though the majority of the earlier wave (1830-1870) were from northern and western Europe and most of the later wave (1880-1920) came from eastern and southern Europe. These immigrants crowded into the cities, often living together in distinct communities, or ethnic neighborhoods demarcated by language, religious and cultural differences. Many of these enclaves—less well-defined and less separated from the surrounding culture—still exist today. Most city governments were characterized by a spirit of laissez-faire (let people do as they please). City government leaders saw their role as one of maintaining civil order, not as engaging in city planning. Generally, as compared with many other industrial countries, this attitude toward planning is still the rule. The American emphasis on individual freedom argues against central regulation and management. Between 1880 and 1920, many urban problems found at least temporary solutions. Movement to bring about social, economic and political reform arose in all the large cities. Collectively, these reform activities came to be known as the Progressive Movement. The same creative impulses that were transforming industrial production were turned to the social problems of the new cities. Public health programs were started and groups were founded to offer help to the poor. Public school systems were enlarged and strict qualification standards for teachers were set. Government reform was brought about partially by a system of promotion for public employees based upon merit rather than upon political favoritism. Housing quality laws were passed. Agencies were created to teach language and job skills to millions of immigrants. In addition, there were many technical innovations that improved the quality of city life. These included the electric light and the electrification of machinery, water and sewage systems, the trolley car and subway, and the elevator and skyscraper. Date: 2015-02-28; view: 1456

|

URBAN CULTURE: THE AMERICAN CITY

URBAN CULTURE: THE AMERICAN CITY