CATEGORIES:

BiologyChemistryConstructionCultureEcologyEconomyElectronicsFinanceGeographyHistoryInformaticsLawMathematicsMechanicsMedicineOtherPedagogyPhilosophyPhysicsPolicyPsychologySociologySportTourism

UNDERSTANDING MONEY

This paper has three objectives: first, to describe succinctly what may be believed to be the history of money; second, to present the different views about money’s origin and its essence held by the Chartalists and Austrian economists; and third, to attempt to understand the validity of their claims.

Transaction costs – For the Austrian economists, money is an institution, spontaneously evolved in society that in order to fulfill its proper role must have some clearly define attributes. But to begin with, it is necessary to answer the question: - proper for what? We will start from this point. The proper role of money in human society is to ease the barters among the producers, to enhance the division of labor, to lower the transaction costs of the exchanges. A medium of exchange was introduced among the barterers with the purpose of “clearing” the exchanges, like in a hypothetical clearance house for all the barters9.

Coherent with the observation of Prof. Douglass North that the costliness of information is the key to the cost of transacting, part of the transaction costs in any deal is associated with the gathering of information about the best opportunities for trade. How can one acquire knowledge about the relative value of a myriad of different goods without a unit of exchange, without a measure of the value of some good against which the value of all the others goods could be referred to? So, a unit of exchange was introduced in order to make transactions easier among barterers by lowering their transaction costs in acquiring information about the relative prices among their respective goods and services. This “unit of exchange” is from now on defined in this paper as the “standard of value”.

Another part of transaction costs that led to the introduction and permanence of money in society is associated with the lack of liquidity in the markets, i.e., the lack of information that makes difficult to match supply and demand for a certain product at a certain price in the absence of some key elements soon to be mentioned. The way to overcome these costs of transaction associated with illiquid markets is by providing a “clearance” service for the community, a service of transferring inventories from where they are abundant to where they are scarce, activity better known as “speculation” or “arbitrage”.

But this activity requires investments in inventories, which on their turn require the existence of “working capital”.

In raising capital either with equity or debt, transference of purchasing power happens; the

power to dispose of goods in society, embodied in the “working” capital, is transferred, in the case we are just describing, to the hands of the service provider and it occurs for a certain period of time. After all, how could obligations with no simultaneous maturities be “cleared” in the hypothetical clearing house of our description? It would be impossible. So, here we meet other reason for the adoption of money in society: the capacity to readily dispose of goods in society that we described as embodied in the “working capital” must be represented by assets of a very special class, assets so generally accepted by the owners of the available goods in exchange for them, that without any coercion, the possession of such assets represents “de facto” the capacity to readily dispose of practically everything available in that society. This special class of assets is money.

It is important to the understanding of our argument (that any generally accepted medium of exchange is money, regardless of the fact that it may be a commodity, a note of credit or a fiduciary currency) to note that this “working” capital can be raised by either equity or debt. Also, it is important to note that this power of readily disposition of goods available in society is not a common characteristic of any asset. What distinguishes the referred “working” capital from a “fixed asset” conceptually? Which goods embody the proper features required to function as “working” capital that other classes of goods do not have? The answer to these questions will help us understand the proper attributes of money; and the failure of such understanding I would like to describe as the “John Law’s second mistake”11.

The Functions of Money – According to Benjamin M. Anderson, Jr. (Anderson, 1917, page 374), the functions of money can be described as:

1) Common measure of values (standard of value);

2) Medium of exchange; 3) Legal tender for debts; 4) Standard of deferred payments; 5) Reserve for credit instruments, including reserve

for government paper money; 6) Store of value; 7) Bearer of options.

As discussed earlier, the crucial function of standard of value was historically only fulfilled with the introduction of a medium of exchange; the 3rd function seems to be part of the 2nd, the 4th part of the 1st, and the 5th and 7th part of the 6th. So the classical list of functions of money, i.e. standard of value, medium of exchange

and store of value, still holds, it is my opinion, although it can be more detailed as described by Prof. B. Anderson.

The central argument of this paper is that good money is money that fulfills properly its purpose. If money has all those functions described above, one may wonder if the most suitable characteristics necessary to better fulfill one of its functions may not be the most suitable feature in order to fulfill other function.

Thinking inside the parameters of the classical list of money functions, I argue that the function of standard of value was historically fulfilled by the introduction of a medium of exchange. And, it is important to note that the function of store of value is better fulfilled by a merchandize with the highest level of liquidity possible, other things being equal. Therefore, the core function of money is its function of medium of exchange as proposed by Menger.

Carl Menger’s GAMOE definition - Because not every good in the market is as saleable as the others, in real life, the most saleable goods became accepted by the individuals in exchange for the goods they produced as a medium to acquire other goods they needed (from now on defined in this paper as medium of exchange). All the other functions of money derive from this primary one, confused with the very concept of money: - the Generally Accepted Medium of Exchange, or the “GAMOE” definition as firstly developed by Carl Menger (Menger, 1994, page 280) and widely accepted today12.

Money for us is a “unit of exchange”, a “standard of value” because it is the preferred medium of exchange. We could have a unit of exchange, a standard of value, that would not be the generally accepted medium of exchange, but in this case the traders would be required to do triangular calculus at each transaction. Money is a “stock of value” because not all exchanges happen simultaneously and the individuals demand the possession of some easily saleable good. What good fits better this purpose? It is the generally accepted medium of exchange, i.e. money. Originally money relies on the trust of the individuals accepting a “monetary” good as an instrument to acquire a certain amount of desirable goods. And any time we are confronted with questions about money, we must remember money’s origins in order to understand its desired properties.

The previous paragraph states no more than a lesson learned from Mises (Mises, 2007, page 401):

“Money is a medium of exchange. It is the most marketable good which people acquire because they want to offer it in later acts of interpersonal exchange. Money is the thing which serves as the generally accepted and commonly used medium of exchange. This is its only function. All the other functions which people ascribe to money are merely particular aspects of its primary and sole function, that of a medium of exchange”.

Money and the division of labor - The main difference between a monetary economy and a barter economy is the limitations of the latter to fully allow the division of labor. A monetary system must be a tool to allow and implement the division of labor. The more this system allows the division of labor, the more proper it is. Besides the absence of money, the division of labor may be constrained by other factors such as the size of market, the cultural background of people, the extent in which property rights are enforceable, et cetera, but it is not part of our goals to inquire about these other constraints.

Suffice to say that ceteris paribus, i.e., (hypothetically) for societies mainly with same size markets, and also same cultural background, etc. it is reasonable to assume a correlation between the intensity in which certain properties are present in the money used by a community and the extension of the division of labor in such community or, in other words, the complexity of its economic activities. It is a relation that works in both ways: a society that lacks labor specialization does not need monies with all the qualities of good money, and without good money labor specialization cannot be further developed. It is not any money that will allow one society to develop industrial activity not to mention complex capital markets. It is worth mentioning that at the time of the Late Roman Republic and Early Roman Empire, they had monies good enough to enable them to run an economy based on trade, agriculture and slavery for centuries, but even that primitive economy crumbled with the less adequate monies of the late Empire13.

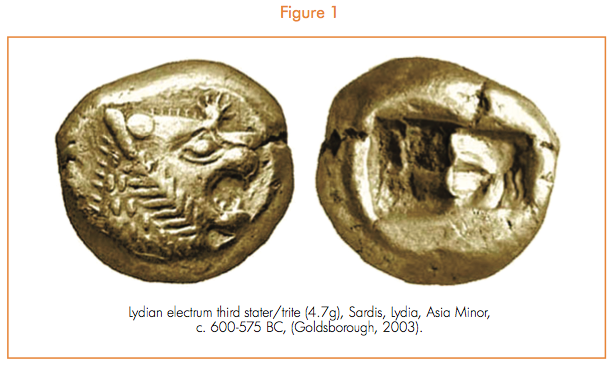

What makes a coined piece of gold (or any other rare metal for that matter) better money than a bag of salt? Gold coins (from now on gold will be referred as a proxy for silver and other metals in this paper) were a more convenient medium of exchange than bags of salt, they were easier to carry, cheaper to store, and gold has higher intrinsic value.

The introduction of money in general and coined gold in particular was due to the convenience of their use, the desirability of their properties as we can imagine from something voluntarily adopted by the people. If the “monetary” goods have the properties desired by the money holders, these goods will ease the exchanges by diminishing the costs of transacting and with this enhance the labor division.

Illusions and misconceptions about money – But is money only the GAMOE? Apparently it is not. Once money is introduced and accepted as a medium of exchange, for some people, money becomes much more than simply an instrument for the goods that you can achieve through it; it becomes desirable by its own sake, something that neither the “preference for liquidity” rationally suggests, nor any rational use of money as a store of value recommends, but by the sheer illusion that so many people have that equates money with personal power, an enabler to buy everything, even “true love” as Nelson Rodrigues, a Brazilian playwright used to say. The dangers of some people entertaining those irrational ideas about money have been well present in philosophy and literature since Plato and Aristotle.

Because of that, one may argue that our account of GAMOE may be true as a norm, but not always as a description, a point made by some Chartalists and I am prepared to concede that. My understanding is that precisely because money is always the GAMOE, it can fulfill other psychological roles as well, with very dramatic consequences in real life, creating illusions and fostering vices. The psychological significance of money and its representation in the arts are topics that I do not intend to discuss in this paper, though.

Is money a creation of the State? - Yet another key characteristic of money could be understood by answering the question: - Is money a creation of the State?

George Friedrich Knapp’s 1905 book State Theory of Money is the cornerstone of the line of

thinking that believes money is a creation of the State. Prof. Knapp starts his books stating that:

“Money is a creature of Law. A theory of money must therefore deal with legal history” (Knapp, 2003, page 1)

To Prof. Knapp, the essence of a currency resides not in the material that its pieces are made of “but in the legal ordinances that regulates their use” (Knapp, 2003, page 2)

According to this school of thought, money has a much narrower definition than the GAMOE definition we are using. Their definition is a sort of tautology: - money is what the law says that money is; money is what the State determines or authorizes, money is what the State gives a charter (reason why this theory is also called Chartalist). Quoting Prof. Knapp again:

“All money, whether of metal or of paper, is only a special case of the means of payment in general. In legal history the concept of the means of payment is gradually evolved, beginning from simple forms and proceeding to the more complex. There are means of payment which are not yet money; then those which are money; later still those which have ceased to be money” (Knapp, 2003, page 2).

There are important consequences of the adoption of this narrow sense for money, first, the value of money becomes ‘nominal’ (reason why this theory is also called Nominalist), i.e. the value of money is, even if indirectly, through the control of money supply, determined by the state; second, since the value of money is determined by the State, the State can change the value of money in order to fulfill its goals and the individuals have no right to complain, after all, if money is created by the State, it is created to attend the objectives of the State, and Prof. Knapp is quite explicit about that:

“Now, when the State alters the means of payment, ..., does anyone lose? Of course; and why not, if the State has paramount reasons for its actions? It can never gain its ends without damage to certain private interests” (Knapp, 2003, page 17)

One may assume that the State is interested in the division of labor and all that, but the immediate interest of the State is its fiscal considerations or other political goals that it may have. A corollary of this understanding about what money is that the ideal attributes of money are not the same ones if you accept that the main purpose of money is to allow and enhance the division of labor; these become factors of secondary significance, more important than those are attributes that one can give to money in order to have in it a more adequate tool for the achievement of government’s policies.

Among the followers of the theory developed by Prof. Knapp, we find John Maynard Keynes, for whom money means essentially the standard of value, (Keynes, 1997, 229) and F. A. Mann who in his 1938 book The Legal Aspects of Money wrote:

“Only those chattels are money to which such character has been attributed by law, i.e. by or with the authority of the State. This is the State or Chartalist theory of money which in modern times has come to be connected with the name of G. F. Knapp, to whose principal work it has given the title” (Mann, 1982, page 13).

Both in the United Kingdom and in the United States of America (and almost everywhere) F. A. Mann’s interpretation is incorporated into the law of the land14.

All these theoretical developments have started from a misconception in my understanding. The fact that the government enforces the currency

is no more a proof that the money is a State creature than the definition of a standard grammar by some state sponsored agency to be adopted by the schools in the country is a proof that the language was created by the State, or the enforcement of corporate law is a proof that corporations are creatures of the State or that marriage is a creation of the State because civil law is enforced by the courts.

Of course it is in the interest of rulers everywhere to say that money is what they say that money is because of the corollaries already mentioned; but it does not become true only because a law says so; if traders use other medium of exchange rather than the government sponsored one, they are using money altogether, no less than blackmail ceases to be blackmail because it is performed by a public persecutor or a lie ceases to be a lie because it is said by a public official in the State’s interest.

That once enforced legal tender, people usually accept fiat money as a medium of exchange is no proof that money is created by the State; if the fiat money is wisely managed as, say, arguably, the American Dollar was managed during Greenspan stewardship, it will be accepted, used and keeps its value in time and in comparison with other currencies; if the fiat money is badly managed, as, for example, the Assignants were during the French Revolution, it will be rejected.

From the fact that nowadays most of the currencies in the world are issued by stated owned monopolies, we cannot derive that, therefore, money is a creation of the State. As stated by Carl Menger in his 1871 Principles of Economics (edited by Huerta de Soto, 2009, page 216, in Spanish): “The origin of money (as distinct from coin, which is only one variety of money) is, as we have seen, entirely natural and thus displays legislative influence only in the rarest instances. Money is not an invention of the state. It is not the product of a legislative act. Even the sanction of political authority is not necessary for its existence”.

Once laws protecting individual’s property rights against violence and fraud are enforced by the state, a generally accepted medium of exchange, i.e. money, will emerge without the necessity of any other state initiative.

Catallactic and Acatallactic theories - In Mises’ The Theory of Money and Credit there is an Appendix “A” on the Classification of Monetary Theories (Mises, 1980, page 503). In this text, Mises presents a broader distinction between ”Catallactic” and “Acatallactic” monetary doctrines according to which all monetary theories can be classified. He explains that “Catallactic” is an adjective meaning something pertaining to exchange and “Catallactics” is a noun meaning the study of commercial exchange. So, the Acatallactic theories about the value of money are those not based on the market observation but on other factors such as (a) the valor impositus, i.e. in the command of the State, (b) biological analogies which equates money to blood, (c) “functional” analogies that compare money with speech, and finally (d) legal jargon that considers money as a draft against everybody else.

It is interesting to note that Mises calls our attention to the fact that the theories that confound the value of money with the value of the monetary merchandise are actually Acatallactic, since they do not take into account that the value of the medium of exchange results precisely from that (although he also notes that this rationale eventually leads to the sources of value of the monetary merchandise and from there to its market value which inevitably takes into account its monetary potential). Prof. Mises even mentions Knapp’s definition of Metallism that: “The metallist defines the unit of value as a certain quantity of metal” is not what Knapp actually means. According toMises, for Knapp, any non-nominalistic theory is a metallist one and so comprising catallactic and Acatallactic ones. Prof. Mises quotes Knapp saying that Adam Smith and David Ricardo were metallists, an “incomprehensible error” if one considers the writings of these authors on money.

For Mises, a consistently developed theory of money must be merged into a theory of exchange, that is, it must be Catallactic and therefore all Acatallactic theories about money can be claimed of being erroneous because they failed to be consistently integrated with the theories about the spontaneous order generated in society by the market interactions of individuals. Mises clearly states that in pointing out the epistemological importance of Carl Menger’s Theory of Money while dealing with “indirect exchange” in Human Action. He suggests that the main deficiency of the doctrine sponsored by those authors who tried to explain the origin of money by the authority of the state or a conscious compact between citizens is their “assumption that people of an age unfamiliar with indirect exchange and money could design a plan of a new economic order, entirely different from the real conditions of their own age.” (Mises, 2007, page 405).

This point is particularly important, since for Mises (Mises, 2007, page 407):

“The historical question concerning the origin of indirect exchange and money is after all of no concern to praxeology. The only relevant thing is that indirect exchange and money exist because the conditions for their existence were and are present”.

Consistent with the idea that historical evidence can support a theoretical understanding about human society but can never prove or disprove it due to the complexity of social phenomena, a preliminary conclusion that can be drawn from these passages is that the introduction of stated coined money in society happened when the social conditions for the development of that specie of medium of exchange were already in place; and therefore, even if it is true that the adoption of coined money was primarily motivated by fiscal considerations, money does not lose its catallactic essence because of that.

Back to Appendix “A” of The Theory of Money and Credit, discussing the “State Theory of Money” Mises calls our attention to the fact that the nominalistic doctrinaires must concede that the State can only establish the validity of money’s nominal unit, “but not the validity of these nominal units in commerce”. (Mises, 1980, page 507) With that he hopes to demonstrate that there is an implicit recognition of the limitations of the theory to actually explain money’s value. But then, he argues, there are always princes interested in the intellectual support of that doctrine for such an important source of revenue as the debasement of the currency, what explains its longevity and good health.

Finally, Mises (Mises, 1980, page 522) uses the contradictory attempt of Philippovich to advance a double definition of money that on the one hand identifies the value of money with the nominal value attributed to it by the State, and on the other, it identifies the monetary unit with its purchasing power to show the sharp contrast between the nominalistic and the catallactic conceptions about money, regardless of Philippovich claims that he is just expressing Knapp’s views with his definition. In opposition to these attempts to find Acatallactic definitions of money’s value, Mises states in Human Action (Mises, 2007, page 418):

“Money is neither an abstract numéraire nor a standard of value or prices. It is necessarily an economic good and as such it is valued and appraised on its own merits, i.e., the services which a man expects for holding cash”.

Date: 2015-02-03; view: 1204

| <== previous page | | | next page ==> |

| METHODICAL_INSTRUCTIONS_ON_writing | | | CONClUSION |